Theatres have been much on my mind lately. When I have an odd moment, I transcribe 18th and 19th-century playbills for the LibCrowds project (there is something soothing about a repetitive task that requires accuracy) and I recently gave a talk on the first night of the Royal Coburg theatre, now known as the Old Vic, of course, as it features in my book The Murder of Mary Ashford.

Neptune and his horses: a spectacular at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London, 1808-1810. The pit had backless benches; the gallery was at the back and was standing.

On the night of Thursday 15 October 1807, John Dobson, his wife, young son and three or four friends were in the pit at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Islington, north London. Although the theatre was exceptionally crowded – it was a benefit night and about 2,000 people were in the house – the audience was good natured and well behaved. Just before the closing scene, at about about ten o’clock, however, Dobson noticed a group of eight or ten people, two of them smartly dressed ‘vulgar women’, join the throng. Some of the men started to push each other about. Dobson, standing on a bench in order to see the stage thought there was something about their behaviour. It seemed to him that the quarrel was staged.

Perhaps a cry of ‘Fight! Fight!’ went up. Perhaps someone misheard it as ‘Fire! Fire!’ This is how many people later explained the panic that spread through the audience and the subsequent rush to leave the building. Seeing what was happening, one of the actors, George Smith, one of the actors, tried to shout to the audience that there was no fire. He was joined by Mr Reeves, one of the owners of the theatre, who got up on stage with a ‘speaking-trumpet’ to do the same, but no one could hear them above the shouting and screaming. The whole house was in chaos, with people jumping 30 feet down from the gallery to the pit to escape the non-existent flames and musicians lifting people over the orchestra onto the stage.

Outside in the yard, those who had escaped were discovering that there had been no fire and heading back inside to find their companions. But their way was blocked by a stream of people still coming down the stairs from the gallery. The result: a logjam. Then someone tripped on the stairs and people started falling on top of each other. It must have happened in moments: a pile of bodies at the foot of the stairs.

In the pit, Dobson, who had seen no fire and nor smelled smoke, had persuaded his party to stay put until the crowd had dispersed.

Sadler’s Wells (1804), John Greig after Samuel Prout. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

There is a terrible irony about the disaster, which arose from fear of flames: Sadler’s Wells’ name remembers the water source (thought to have healing powers) it was built over and in the winter of 1803 the manager, Charles Dibdin the Younger, installed a large water tank (80 by 30 feet) at stage level and filled it from the nearby New River. The following season he staged the astonishing spectacle The Siege of Gibraltar, during which scale models of ships were moved around the ‘sea’ by boys wearing ‘thick duffel trousers’ and encouraged with brandy.

A contemporary observer wrote:

It acted like electricity, a pause of breathless wonder was succeeded by stunning peals of constant accclaimation; and when the Ships sailed down, in regular succession, ‘rolling on their way’, their sails shifted in the wind; their colours and pennants flying; and their ordnance, as they passed the front of the stage, firing a grand salute to the Audience, the latter seemed in an extasy.

Sadler’s Wells came to be known as ‘the aquatic theatre’.

Charles Dibdin the Younger in 1819. Courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Dibdin was trying to improve Sadler’s Wells’ reputation for attracting drunken loutish audiences. Not only was he offering the escorts back into central London after dark (Islington was then still a rural suburb) but he started hiring famous performers such as the Shakespearian actor Edmund Kean and the clown Joseph Grimaldi.

After the panic was over, about 30 bodies were brought into the proprietor’s room, 18 of whom were obviously dead, killed by suffocation or crushing. Mr Sharpe, a surgeon from St Bartholomew’s who happened to be in the audience, worked hard to save the other 10 or 12 with other medics who had been sent for. One victim was ‘an athletic man’ who came round after he was bled, only to find his wife lying dead next to him. ‘The poor fellow became frantic, and was carried away in a state of desperation,’ according to some reports.

The injured were removed quickly: a sailor from The York, who had been severely bruised, to The London Hospital in Mile End Road; five others to Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite the theatre; and four to Islington Spa. Some had broken bones but all of them are thought to have recovered.

Four of the ‘ruffians’ who had started the fake fight were arrested. John and Vincent Pierce, Mary Vine and Elizabeth Luker were taken before the bar at Hatton Garden. Despite their apparent callousness (when they were informed that 18 people had died as a result of their ‘riot’, they were alleged to have said something along the lines of ‘Well, we don’t care. We can’t be hanged for it’) they could not be charged with a felony crime. Their actions were intended to distract the audience while they picked pockets, not to result in death.

The Sir Hugh Middleton’s Head, opposite Sadler’s Wells Theatre. Credit: Wellcome Collection

A mob gathered outside the theatre and the Clerkenwell Volunteers were called in to control them, while inside the theatre in three separate rooms the 18 bodies (‘horribly disfigured and contorted’) were being ‘decently laid out upon temporary tables’ and labelled with their names and addresses, ready for the Coroner. They were overwhelmingly young people and included at least five children aged 16 or under:

John Ward, 16, an errand boy, of Glasshouse Yard, Goswell Street, was identified by a 17-year-old friend Mary Ann Pede, who lived next door and who had gone with him to the performance. They became separated after the cry of ‘Fire!’ went up.

Lydia Carr, of 23 Peerless Pool, City Road, identified by her brother John

Elizabeth Margaret Ward, 21, of 20 Plumtree Court, Bloomsbury, was identified by her mother. Elizabeth had gone to the theatre with her sister and ‘a young man’ who were too injured to attend the inquest.

Benjamin Price, 12, of 33 Lime Street, Leadenhall Street

Joseph Groves, a servant to Mr Taylor of Hoxton Square, identified by his brother John

Edward Clements, 13, of Paradise Court, Battlebridge, identified by his father John.

John Labdon, 20, of 7 Bell Yard, Temple Bar

John Greenwood, an apprentice, of King Street, Hoxton Square, identified by his employer, John Simmons

Sarah Chalkey, of 24 Oxford Road, identified by Mr Monk, a War Office messenger.

Rhoda Ward, 16, of The Crooked Bill, Hoxton, identified by her mother Martha, who had been in the gallery with her daughter.

Mary Evans, of Hoxton Market, identified by her son William and sister Sarah.

Caroline Terrell (sometimes given as Twitcher), an ‘unfortunate woman’, who was pregnant, of Plough Court, Whitechapel, identified by Class Jacobs, a Swedish sailor from The York, who had been with her for three days before they went to the theatre together.

James Philliston, 30, of White Lion Street, Pentonville

Rebecca Sanders, aged 9, a domestic servant, of 12 Drapers Buildings, London Wall, identified by her father. She had gone to the theatre with her mistress to help mind the baby.

Rebecca Ling, of 5 Bridge Court, Cannon Row, Westminster, identified by John Myers

Richard Bland, 28, of 13 Bear Street, Leicester Fields

Charles Judd, 20, of Artillery Lane, Bishopsgate Street

William Pincks, 17, of Hoxton Market, identified by his mother Mary Pincks

Most of the dead were found to have little money and no valuables on them. The coroner’s clerk retrieved only 20 shillings (£1) from them in total. As they were, in the main, people of slender means this was not perhaps surprising, but there remained a suspicion that the bodies had been robbed.

George Hodgson, the Middlesex Coroner, arrived at ten ‘clock and convened the inquest in Mr Dibdin’s drawing room. Then the jury viewed the bodies, the stage and the gallery stairs and were satisfied that no fire had occurred. The friends and relatives of the dead gave evidence as did actors and employees of the theatre. At the conclusion, Mr Hodgson instructed the Jury, who duly declared that the dead had been killed ‘casually, accidentally and by misfortune’. Hodgson praised the management of Sadler’s Wells who had acted ‘most becomingly’ and had done everything they could to prevent the panic.

The four prisoners appeared at Middlesex Magistrates Court. Mary Vine was remanded to Clerkenwell prison and the others were bailed.

The following day, Sunday, the bodies were taken away for burial. Dibdin, who paid the funeral expenses of the ‘unfortunate’ Caroline Terrell as no relatives came forward to claim her body, was plagued with false claims for expenses.

On 2 November the theatre reopened for a two-night benefit for the relations of the victims.

In December, John and Vincent Pierce and Elizabeth Luker were sentenced for exciting a riot and disturbance at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. After Mr Mainwaring lamented their ‘outrageous conduct’ and the terrible consequences of it – ‘whole families plunged in irremediable ruin, by the loss and protection of those who were their natural protectors and guardians – he gave John six months, Vincent four and Elizabeth 14 days imprisonment.

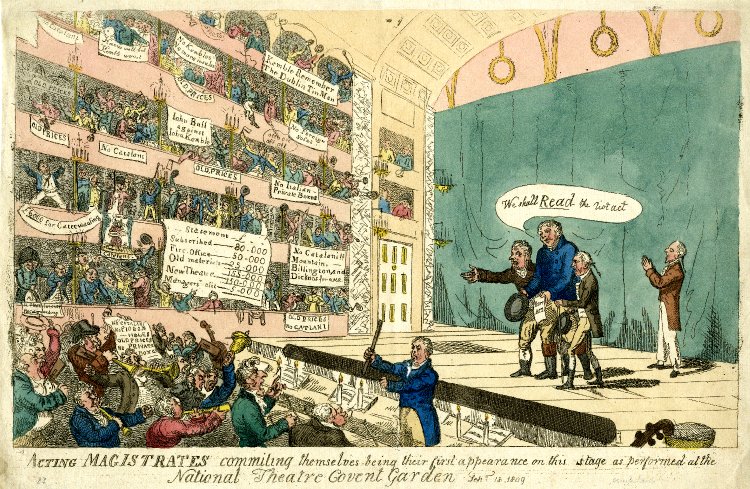

Acting magistrates committing themselves being their first appearance on this stage as performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden. Sepr 18 1809. © British Museum, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The danger of fire in theatres was real. Ideas for improved safety, suggested by journalists rather than by the authorities, included having ready-made banners at hand to tell people that the theatre was not on fire, and making sure that there was enough space for fleeing people to congregate without blocking exits for other people. However, nothing changed and nearly a year after the Sadler’s Wells tragedy, Covent Garden Theatre was destroyed by fire with the loss of 30 lives, and Drury Lane Theatre burnt down in March 1809.

Commotions among theatre audiences were a regular occurrence. When Covent Garden Theatre reopened in 1809 the audience took the management’s decision to raise ticket prices as an outrageous infringement of their rights and three months of riots ensued, during which, it is said, 20 lives were lost. The violence only ended with the manager, John Philip Kemble, reverting prices and apologising.

Sources

The Annual Register for the year 1807 (1809). London: W. Otridge and Son et al.

McPherson, H. (2002). Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London. The Eighteenth Century, 43(3), 236-252. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41467906

Remington, S. (1982). Three Centuries of Sadler’s Wells. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 130 (5312), 472-481. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41373417

Morning Chronicle, 26 October 1807, 3B.

Morning Post, 17 October 1807, 3C; 19 October, 3D; 24 October 1807, 4B; 9 December, 4B.

Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 17 October 1807, 3B; 19 October, 3B.