One of the leather gauntlets used in the last-ever legal challenge to trial by battle in an English court has been sold at Christie’s in London for £6,875 two hundred years after its pair was dramatically thrown down in Westminster Hall.

One gauntlet was thrown down in Westminster Hall. The other, shown here, was kept in the family of Thornton’s solicitor Edward Sadler until it was sold at Christie’s on 10 July 2019.

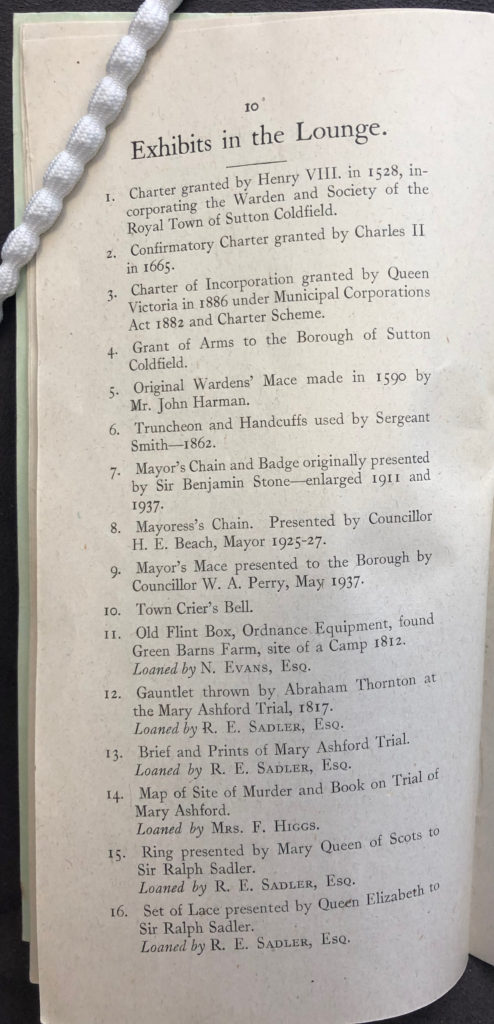

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in 1942, when it was displayed at Sutton Coldfield town hall, as part of an exhibition of local artefacts.

The documents sold with the gauntlet in the lot include the original of Edward Sadler’s brief to Thornton’s barristers for the Warwick trial for murder and rape.

The gauntlet was preserved by Thornton’s solicitor, Edward Sadler, whose offices were in the High Street, Sutton Coldfield, and remained in his family, passing down through the generations to his great-great-great-great grandson Magnus Bowles, a specialist bookseller, who put it, and associated documents, up for sale at Christie’s.

As a family we are very hopeful that the gauntlet will find a new home in an institution where it can be on display for all. It is testament to a remarkable human story – the tragic murder of Mary Ashford – and a dramatic and historic legal one.

Magnus Bowles, a descendant of Edward Sadler

In a case that made legal history, Abraham Thornton, a bricklayer from Castle Bromwich, who was accused of murdering Mary Ashford in the village of Erdington near Birmingham, threw down one of two gauntlets in the middle of a packed Court of King’s Bench in Westminster Hall, London on 17 November 1817, crying, “Not guilty and I am ready to defend the same with my body.” Thornton demanded a ‘Wager of Battel’ with his prosecutor. The whereabouts of this gauntlet—rumoured to have been given to the British Museum—is currently unknown. The second gauntlet had been kept in family of Thornton’s solicitor Edward Sadler for 200 years.

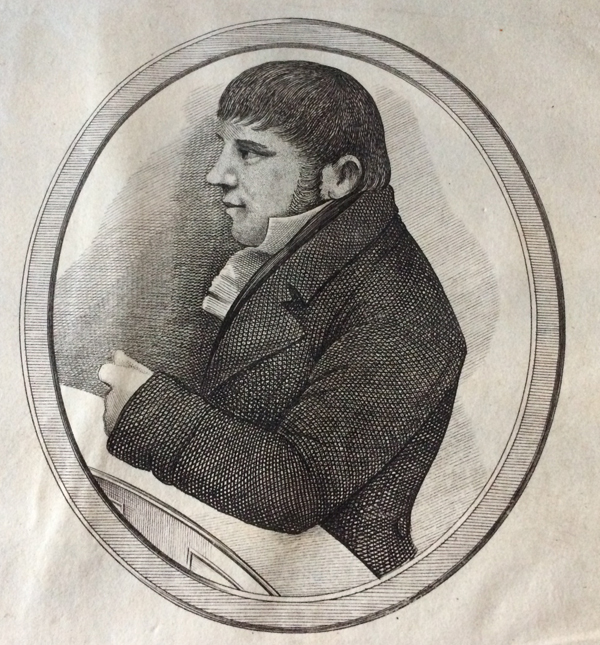

Strong evidence against Abraham Thornton was presented in court at Warwick but all of it was circumstantial. After the verdict a prison snitch came forward with additional information that lay in the archives for 200 years. Image from the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 24 January 1885.

Three months before the challenge, Thornton was acquitted at Warwick Assizes, but Mary’s brother William Ashford dragged him back to court in London for a private prosecution using an archaic law known as Appeal of Murder. Abraham Thornton’s lawyers decided to use an equally outmoded law asserting his right to decide the case in a one-to-one duel in which the protagonists would fight each other equipped only with cudgels and shields.

Not guilty and I am ready to defend the same with my body.

Abraham Thornton’s response in Westminster Hall, when asked if he was guilty of the murder of Mary Ashford, as he threw down the gauntlet.

The legal fraternity was horrified that such a barbaric event could take place in the modern age but after a protracted series of legal arguments, the judges sitting on the case conceded that a trial by battle was legal and could proceed. The case collapsed when William was forced to withdraw—Thornton was a beefy bricklayer and William, who was small and slight, stood no chance. Appeal of Murder and Trial by Battle were removed from the statute the following year. After his return to Castle Bromwich Abraham Thornton was ostracised by his neighbours and emigrated to America.

Abraham Thornton, from a sketch taken in court. From J. Cooper’s A Report on the Proceedings Against Abraham Thornton at Warwick Summer Assizes, 1817…

Mary Ashford was buried in the churchyard at Holy Trinity in Sutton Coldfield. The inscription on her gravestone, paid for by public donations, calls her murderer ‘a wretch’ whom ‘avenging wrath’ will pursue. Every year a local resident lays flowers on her grave. The case attracted huge attention across the country and inspired several popular plays. Crowds flocked to Westminster Hall to catch a glimpse of Thornton as he arrived for the hearings. It was said to have inspired Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

Mary Ashford’s gravestone at Holy Trinity Church, Sutton Coldfield. Very little of the inscription is legible.

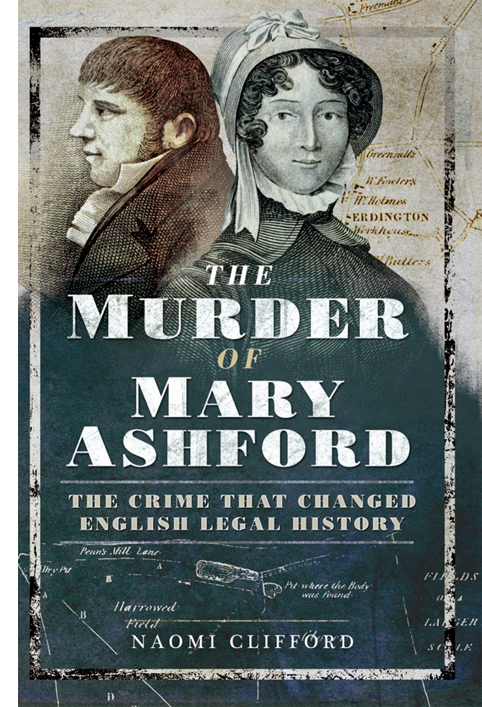

Unknown to the public, a convicted felon called Omar Hall who had shared a cell with Thornton came forward with additional evidence against him but William Ashford’s lawyers decided not to pursue this course: to do so meant they would have had to obtain a royal pardon for Hall, and they also felt that his testimony, as a prison snitch, would have been distrusted. There are more details about this evidence in my book The Murder of Mary Ashford.

The Murder of Mary Ashford: The Crime That Changed English Legal History, published by Pen and Sword.

The gauntlet, of white kidskin, is in excellent condition. It is decorated with green silk embroidery, a ribbon of red leather and a green silk fringe. The missing pair is said to have ended up in the British Museum but has not so far been traced.

The gauntlets were not “a pair”—that is, right and left—but were both alike; one pouch, without separate fingers or thumbs, as ordinary gloves have. The size of the glove is ten inches long, and nine in circumference round the middle of the palm; so that, although large enough to contain a man’s hand, the width is too narrow to admit of the hand being so placed as to grasp anything, as the thumb must underlie the fingers in the middle of the palm. From the wrist it expands considerably, as ordinary gauntlets do in a slight degree. Round the wrist is a sprayed ornament of dark and lighter green silk, embroidered with the crewel stitch now called “crewel work”; below that and nearer to the edge is a narrow band of red leather, three-eighths of an inch wide, with a small ornamentation of green silk cross stitches at the inner edge, and a narrow green silk fringe at the extreme edge next the arm. From the wrist depend three leathern tags, having four holes in each, through which, doubtless, were to be threaded the ten white leather thongs, each sixteen inches long, to fasten the gauntlet round the wrist. The gauntlet is made of white tanned sheep-skin, without a seam of any kind in it. It has long been a source of perplexity as to what it could have been made of; but from an examination of it the other day by two eminent Birmingham surgeons, it was decided that it was formed of a ram’s scrotum, as on it are to be seen the marks of the two rudimentary teats situated near to such a formation.

John Rabone, Notes & Queries, Series 6, xi (1885), p.462-3.

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in September 1942, when a great-grandson of Edward Sadler, Richard E. Sadler, lent it to the Sutton Coldfield Photographic Society for an exhibition along with other items.

The last time the gauntlet was seen in public was in September 1942, when a great-grandson of Edward Sadler, Richard E. Sadler, lent it to the Sutton Coldfield Photographic Society for an exhibition along with other items. The catalogue states that the gauntlet shown was the one thrown down in Westminster Hall (item 12), which is unlikely to have been the case.