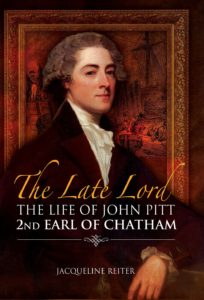

I am thrilled to welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog today. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook (www.facebook.com/latelordchatham) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/latelordchatham). Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.

I am thrilled to welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog today. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook (www.facebook.com/latelordchatham) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/latelordchatham). Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.

Historical aristocratic marriages do not always come across positively, partly because most such marriages that are remembered today stick in the mind because of their disastrous nature. The late Georgian period alone is full of such tales, from the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire’s curious ménage-à-trois with Lady Elizabeth Foster, through public divorce sensations like Sir Richard and Lady Worsley, to the most infamous celebrity mismatch of the period, the Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick.

Sometimes, of course, aristocratic marriages were successful, as I had the pleasure of discovering while researching my biography of the 2nd Earl of Chatham, the elder brother of British prime minister William Pitt the Younger. In a period so apparently full of failure, Lord and Lady Chatham’s 38-year marriage was a model of tranquility. Unfortunately, in this case, a happy marriage did not automatically mean a happy ending.

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, married Mary Elizabeth Townshend on 10 July 1783. Their courtship was long and rather drawn-out on Lord Chatham’s part, but probably due to bashfulness rather than reluctance. Their fathers had been close friends and neighbours, and John and Mary had known each other since they were children. Their names had been paired up as early as 1779, when Mary was 16 and John 22.

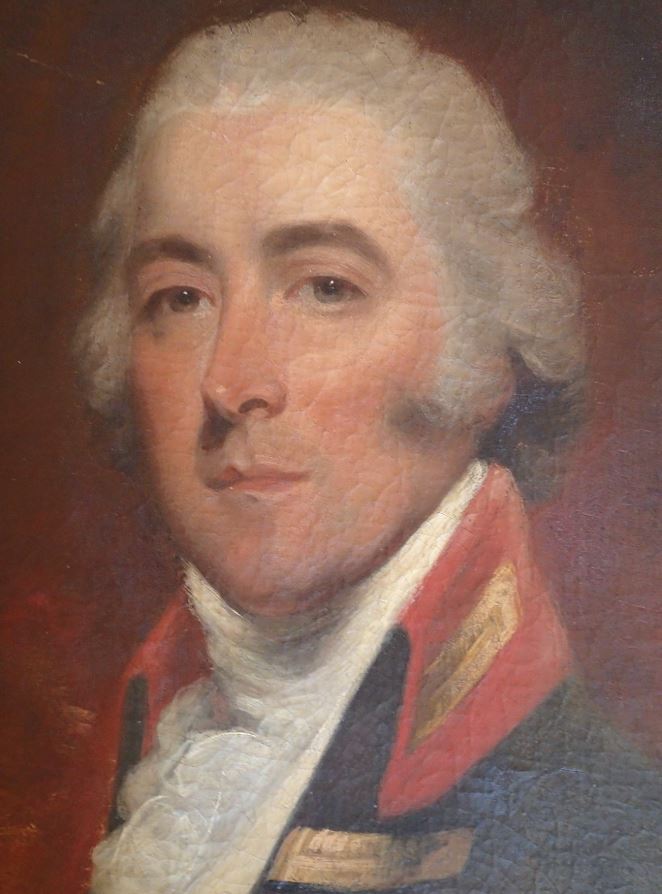

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, studio of John Hoppner (1799, courtesy of the Commando Forces Officers’ Mess, Royal Marines Barracks, Plymouth)

The Pitt and Townshend families were both delighted with the match. Mary’s father, Lord Sydney, wrote to John’s mother of his “Satisfaction & Pride in placing a Part of my Family, which deserves & possesses my warmest & most tender Affection, under the Protection of those, whose Alliance, I can truly say, I prefer to that of any Family in England”.1 Twelve years later, John’s mother still had no doubt her son had made the right choice. She told Lord Sydney: “I have been always proud of the Prize obtain’d by my Son Chatham, from your Family.”2

John and Mary’s feelings are less easy to work out, as no letters between them survive. This itself, however, testifies to their closeness, as for the first 24 years of their marriage they seem to have been rarely apart. Even when Chatham, a soldier by profession, went off on campaign, Lady Chatham followed him as far as she could. She took her duties as a soldier’s wife seriously: she regularly accompanied her husband on the parade ground, watching manoeuvres from an open carriage, and she was by his side throughout his military district postings, moving from barrack to barrack in Winchester, Chatham, Eastbourne and Colchester. This did not mean she enjoyed watching her husband march off to war. “As to his fighting again, I believe I had better not answer that at all, for fear of being a little warm,” she wrote during the brief Peace of Amiens in 1802. “…I believe I may as sincerely wish the Peace to last, as a friend to my Country, as I do as a Wife.”3

Seal of Lord Chatham, showing his arms impaling those of his wife (private collection)

The strength of their marriage, however, was far more obvious when things were going wrong than when they were going right. Tragically for the Chathams, things often went very wrong right from the start. For two years from April 1784 Mary was almost completely crippled by some sort of rheumatic disorder in her knee and hip, and she walked with a limp for the rest of her life. She remained reasonably healthy for the next 20 years, but in 1806 her health again collapsed. For several weeks she was afflicted by a “delirious fever” and unable to leave her bed.4 Physically she was back to normal by the end of the year, but her mental health continued to decline.

By 1807, Mary Chatham was what we would now describe as clinically depressed. She continued appearing in public life – her husband was, after all, a cabinet minister – but the strain of keeping up a pretence of normality was distressingly obvious to her family. Her unmarried sister Georgiana kept Mary’s doctor, Henry Vaughan (later Sir Henry Halford), updated on her outbursts of violence, shocking language and threats of suicide. Following what was probably an unsuccessful attempt to end her life in October 1807, Mary at last disappeared from public life. She did not return to it for two years.

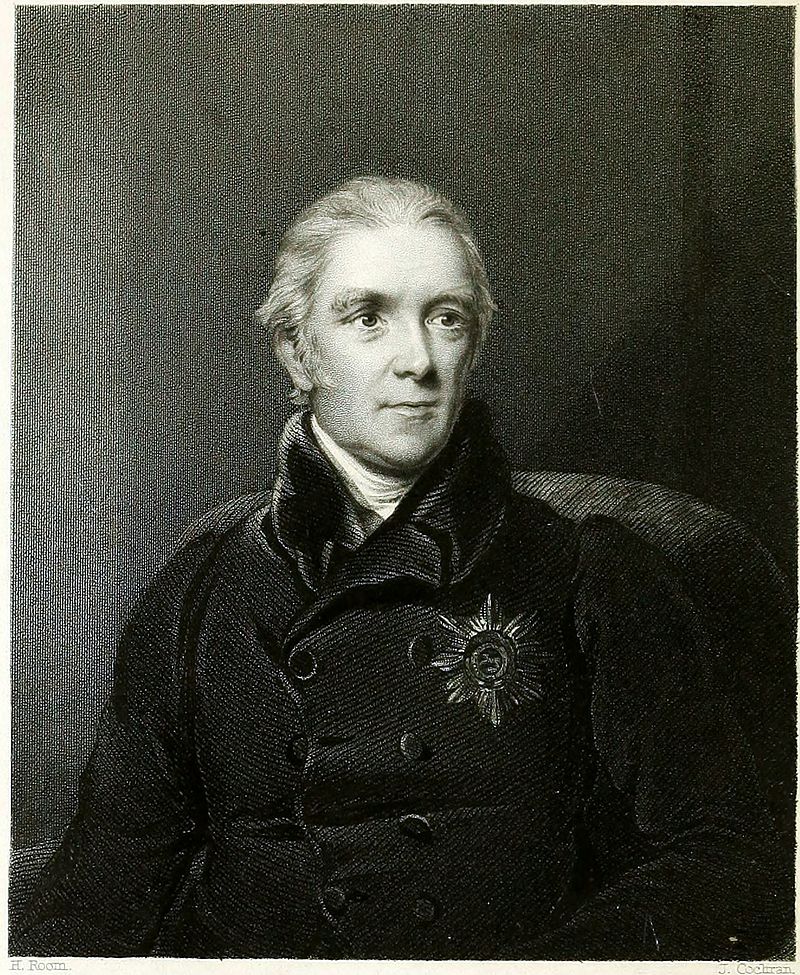

Sir Henry Halford (Wikipedia Commons)

The impact of Lady Chatham’s illness on her marriage was worse than anything she and her husband had ever experienced. At first, Chatham refused to believe what was happening. He was always inclined to pretend that tremendous personal crises did not exist, and it took him months to realise his wife was extremely ill. “Nobody thinks her well, but him,” Georgiana Townshend remarked sadly.5 Eventually, of course, Chatham could no longer hide from the truth, and he and Mary spent much of the following two years apart as she recovered and he tried to focus on his public career.

Remarkably, their marriage survived. When Mary recovered in 1809, the pair returned to public life together as though nothing had happened. This is not to say Mary’s illness did not leave deep scars. Hints that their relationship was overshadowed by the fear of relapse appeared in Chatham’s private correspondence. He kept bad news from her, made decisions alone, and admitted he tried his best to “make everything appear to the best”.6

Chatham was right to be worried, although for nine years Lady Chatham was perfectly healthy. In March 1818, however, she relapsed. The symptoms of violence, self-harm and deep depression were almost exactly the same. This time Chatham, by now out of office, nursed his wife more or less alone. He was now in his mid-sixties himself, and friends noticed the effects of the strain on his health: “He cannot much longer support such a scene of suffering.”7 Chatham was eventually persuaded to hire a “companion” skilled in cases of insanity to allow himself a few days of relief, but to his credit he strongly resisted his doctor’s suggestions of straitjacketing, and never failed to add Lady Chatham’s remembrances to his letters, even when she was at her worst. (This was in stark contrast to Lady Chatham’s doctor, who referred to her as a “poor Creature”.)8

The end came on 21 May 1821, and it was just as tragic as the rest of the story. At five in the evening Lady Chatham, who had been ill, took a glass of barley water and brandy mixed with laudanum and went early to bed. She never woke up. Chatham was at dinner with a guest at the time; it was his guest who found Mary lying as though in a deep sleep, “without a feature altered”.9

Friends and family expressed relief that she was at last relieved from her suffering, but Chatham was devastated. He did not recover from losing his wife for at least a year, and displayed signs of profound depression far beyond that. Despite her mental problems, Mary had still been the only family he had left.

Mary Elizabeth, Countess of Chatham, possibly by Edward Miles, 1789 (private collection)

On Chatham’s death in 1835, one of the heirlooms passed down to his executors – his great-nephews, as he and his wife never managed to have any children of their own – was a portrait miniature of Mary Chatham from 1789. The miniature is still in the family’s possession today. It depicts a fresh-faced, 26-year-old girl dressed to the height of fashion, peering coyly at the viewer from under an enormous hat. To Chatham, the miniature must have been memories of happy times.

- Lord Sydney to Lady Chatham, 5 June 1783, TNA Chatham Papers PRO 30/8/60 f 205.

- Dowager Lady Chatham to Lord Sydney, 2 February 1795, Huntington Library Townshend Family Papers TD 284.

- Lady Chatham to Mrs Stapleton, undated, National Army Museum Combermere MSS 8408-114.

- The Bishop of Lincoln to his wife, 31 January 1806, Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/T99/26.

- [Georgiana Townshend] to Dr Vaughan, 14 April [1807], Leicestershire Record Office Halford MSS DG 24/819/1.

- Chatham to Mrs Stapleton, 2 December 1810, National Army Museum Combermere MSS 8408-114.

- Elizabeth Tomline to Sir Henry Halford, [September 1819], Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/562/716.

- Sir Henry Halford to Elizabeth Tomline, 10 September 1819, Suffolk Record Office Pretyman-Tomline MSS HA 119/562/716.

- William Sloane to the Duke of Rutland, 22 May 1821, Belvoir Castle Manuscripts.

Leave a Reply