Madame de Genlis’s Ideas of an 18th Century Education by Geri Walton

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to study for a degree in History and resulted in her website, Geri Walton: unique histories from the 18th and 19th centuries which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s.

Geri Walton has long been interested in history and fascinated by the stories of people from the 1700 and 1800s. This led her to study for a degree in History and resulted in her website, Geri Walton: unique histories from the 18th and 19th centuries which offers unique history stories from the 1700 and 1800s.

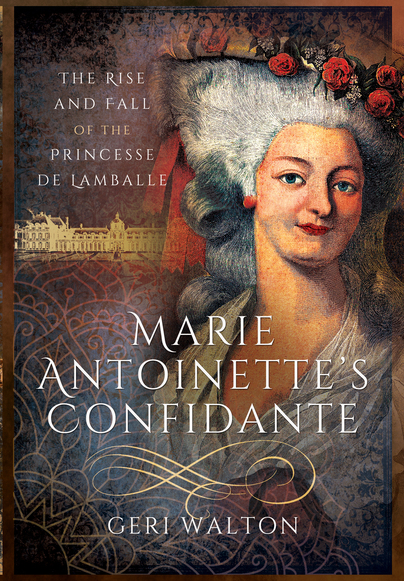

Geri’s first book, Marie Antoinette’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe, is due to be released by Pen & Sword in October 2016. It looks at the relationship between Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe, and among the people mentioned in the book is Madame de Genlis.

You can find Geri on Facebook, Twitter (@18thcand19thc, Google Plus, Instagram (@18thcand19thc), and Pinterest.

Madame de Genlis (Author’s Collection)

From an early age, Stéphanie Félicité du Crest de Saint-Aubin was a forward thinker intrigued by learning and education. She was also a harp prodigy whose wittiness and capabilities were noticed by Charles-Alexis Brûlart, Comte de Genlis (afterwards Marquis de Sillery). He was ‘struck with the style of a letter which accidentally fell in his way, [and] conceived so high a sentiment of admiration for the writer, that he immediately made her an offer of marriage [without having met her].’ Thus, at the tender age of 16, Stéphanie became Madame de Genlis.

Because of her wittiness and skills, Madame de Genlis found herself employed by the Duchess of Chartres as a lady-in-waiting, but it was her education of her own children that caught the eye of the Duchess’s husband, the Duke of Chartres. Later, he was also captivated by her sexuality, and the two enjoyed a brief love affair. While working as a lady-in-waiting, Madame de Genlis’s first writings included ‘moral and entertaining dramatic pieces, which her children performed in the presence of the duchess of Chartres [after 1766].’ Madame de Genlis later published these plays (between 1779 and 1780) under the title of ‘Theatre for the Use of Young persons, or Theatre of Education’.

After Madame de Genlis and the Duke ended their affair, Madame de Genlis continued to have a power over him and that is likely part of the reason why the Duke involved her in his children’s education. Later, in 1781, the Duke went a step further and boldly declared her gouverneur (not governess) of his sons. At the time a gouverneur was a position held only by a man and the appointment created a scandal: Rumours flew that Madame de Genlis and the Duke were having an affair, although by this time their affair was over. Moreover, with her new appointment, Madame de Genlis was unwilling to share power and was reputedly so dictatorial in how and what the children should learn that all the other tutors resigned.

Louis Philippe d’Orléans, as Duke of Chartres, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, c.1779 (Courtesy of Château de Chantilly)

As gouverneur, Madame de Genlis instituted teaching techniques that were unusual and forward-thinking for the times. For example, history was taught with the help of slides using an early image projector called a magic lantern, and botany studies were conducted by a real botanist while the children went out for their daily walk. Madame de Genlis also believed her students should be self-reliant, sleep on hard beds, and get plenty of exercise. In fact once she reportedly put lead in the boots of Louis-Philippe, the boy who would grow up to be Louis Philippe I (King of France from 1830 to 1848), and made him walk for miles.

Madame de Genlis was reputedly also a strict taskmaster when it came to learning and education. Her students’ activities began as early as 6.30 in the morning, and the children were kept busy all day. Subjects the children studied included literature, mythology, mathematics, chemistry, geography, physics, and anatomy. Foreign languages were also greatly emphasized, and the children practiced them regularly learning Italian from the chambermaid, German from the gardener, and English from the valet. Yet despite her strictness, her students adored her and sweetly called her ‘Bonne Amie’ or ‘Maman Genlis’.

Madame de Genlis also provided plenty of first-hand experiences and hands-on lessons for her pupils. Field trips were an important part of her curriculum. This resulted in the children visiting a variety of places that included factories, artist studios, and furniture manufacturers. The children also took numerous educational vacations to places such as Normandy, Chantilly, or Spa. Moreover, after the attack by revolutionaries on the Bastille, she took the children to visit the infamous site.

From the garden terrace of her friend Beaumarchais, Mme de Genlis, surrounded by her pupils, watched ‘men, women, and children working with unprecedented ardour’ at the demolition of the fortress…And she shared the joy of the destroyers at the fall of the fortress, on which, so she said, she had never been able to look without a shudder, remembering the arbitrary imprisonments within its walls.

The children’s religious instructions were also not neglected. Madame de Genlis read the Bible to the children faithfully for an hour a day, and when Louis-Philippe was slated to receive his first communion, she undertook to prepare himself for the event. To prepare him, however, she stepped on toes and her pushiness was ‘vociferously protested by the chaplain, l’abbé Guoyt, and seen by many others…as an arrogant usurpation of his theological function.’

Louis Philippe I in 1841 by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

Over the years, if Madame de Genlis was said to have one outstanding talent, it would have been writing. She was a prolific writer, and one person noted she loved it so much ‘she would have invented the inkstand… if the inkstand had been uninvented.’ It was said of her that her pieces were diverse enough to be enjoyed by princes or lackeys and that she “essayed almost every style, from the fugitive piece to the bulky alphabetical compilation, from the roman-poeme to the treatise on domestic economy and the collection of receipts for the kitchen.”

Madame de Genlis’s husband was guillotined in 1792, and although Madame de Genlis favored the French Revolution, she sought safety in Switzerland after the fall of the Girondins in 1793. At this time most her students had grown, and she spent much of her time writing and producing historical novels. In 1814, her ability to write became more important than ever after Louis XVIII discontinued her pension. There was also one other sad note. Her old pupil Louis-Philippe, who had been so enamored with her when he was young, now rarely visited her. However, she did see him crowned King of the French on 9 August 1830, four months before she died on 31 December 1830 at the age of seventy-six.

References

The Analectic Magazine, Volume 14, 1819

Dobson, Austin, Four Frenchwomen, 1895

Hardy, Blanche C., The Princesse de Lamballe, 1908

Robb, Bonnie Arden, Félicité de Genlis: Motherhood in the Margins, 2008

Whale, Winifred Stephens, Women of the French Revolution, 1922

© Geri Walton

[…] Duke’s wife), the Princesse de Lamballe (the Duke of Chartres’s sister-in-law), and Madame de Genlis (the Duke of Chartres’ lover). Because so many influential and noble women attended meetings […]