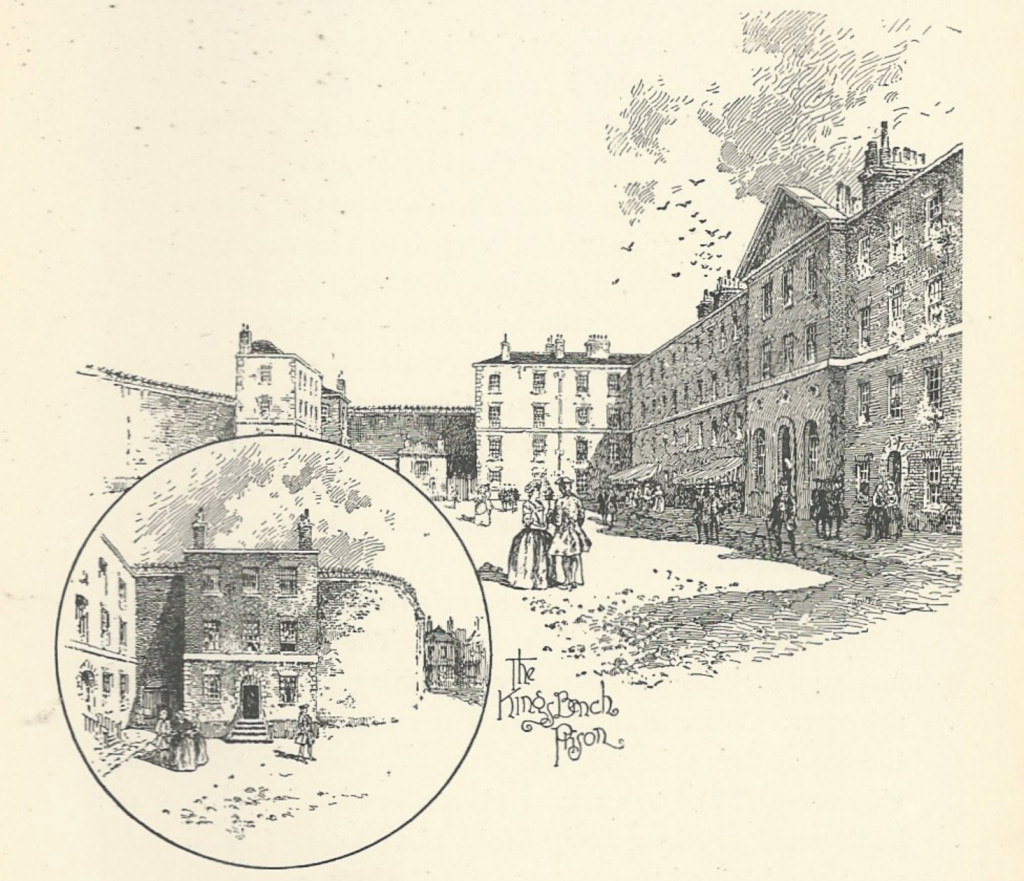

The King’s Bench prison, encircled by high walls surmounted by sharp spikes, sat in an area of dank reclaimed marshland close to St George’s Fields at Newington, Southwark, on the south side of the Thames. The site is approximately where the Scovell housing estate now stands.

This area had four jails within a small radius but imprisonment was just one of the local industries. Prostitution was another, along with brewing, hat-making, leather and provisioning. It was a busy, smelly, bustling, dusty district.

The prisoners were a strange mix of ‘nobles and ignobles, parsons, lawyers, farmers, tradesmen, shopmen, colonels, captains, gamblers, horse dealers, publicans, butchers.’ In an essay for The Uncommercial Traveller in 1860, Charles Dickens, who had known worse conditions when his father was locked up for debt in the nearby Marshalsea, and who as a twelve-year-old boy had lodged only a few streets from the King’s Bench Prison, recalled his impressions of the inmates. They were dying from what he called ‘dry rot,’ ‘a certain slovenliness and deterioration, which is not poverty, nor dirt, nor intoxication, nor ill-health.’1

The prison operated a system of liberties, or Rules, as they were called, that allowed inmates to live in — or just to visit for the day — an area about three miles in circumference around the prison. All they had to do was pay a fee to the Marshal. They were not supposed to stray beyond the boundaries of the Rules but enforcement was lax. When Lord Chief Justice Ellenborough was applied to for an extension of the Rules he gravely replied that he really could see no grounds for it since to his certain knowledge they already extended as far as the East Indies.

Dickens described seeing inmates on the streets. They had ‘a tendency to lurk and lounge; to be at street-corners without intelligible reason; to be going anywhere when met; to be about many places rather than at any; to do nothing tangible, but to have an intention of performing a variety of intangible duties to-morrow or the day after.’2

Like other prisons of the time, the King’s Bench Prison had facilities that make it sound, if not luxurious, at least convenient. The yard had a coffee house, two pubs, butchers’ stands, chandlers’ shops and a surgery. Sometimes it was given over to an open-air market where hawkers of all kinds plied their wares. There were racket grounds and fives courts. But life inside was anything but easy. Inmates were responsible for finding their own bedding, food and drink, which were available only at inflated prices. Often five or six hundred of them were squeezed into two hundred and twenty-four tiny cells, most less than nine feet (three metres) long. The rich prisoners could live in one of the eight ‘state rooms’ but those on the breadline lived by begging or on the charity of their fellows. At times of the most severe overcrowding, the ordinary prisoners shared their rooms with the paupers, but they could opt to pay their ‘chum’ to sleep elsewhere, usually the benches of the pub or on the floor and seats of the chapel.3

Writing in The Examiner in 18034 Leigh Hunt made an impassioned attack on the state of London’s prisons, the King’s Bench in particular. He wrote from the heart — he had been imprisoned there as a young child, when his father had been a debtor.

In their confined and unwholesome abodes, aged and unhappy parents may be seen lamenting over their offspring — respectable wives watching the sick beds of their husbands — children partaking of the scanty meals of their afflicted parents, — and that meal, perhaps procured by the sacrifice of some necessary piece of raiment… This is not an imaginary picture, but a common and every day scene.

A year later The Examiner published a letter that bore out his description: ‘No medical aid; no allowance of food — every prisoner who is without resource must take his turn in holding the begging box; and many, rather than submit to that degradation, have shut themselves up in their rooms and have become so emaciated from want as to produce disorders that terminated their miserable experience — no bedding provided.’5

- All the Year Round, 21 July 1860. Charles Dickens also wrote of the prison in three novels: in David Copperfield the feckless Mr Micawber is imprisoned there; in Nicholas Nickleby Madeleine Bray and her father live within the Rules; and in Little Dorrit Mr Rugg tries to persuade Arthur Clennam to go to the more spacious King’s Bench Prison rather than the squalid Marshalsea nearby. In 1824, the 12-year-old Dickens lodged in Lant Street, close to both the King’s Bench Prison and the Marshalsea, where the rest of his family was imprisoned for debt.

- The description of the King’s Bench Prison has been compiled from various contemporary sources: John Richardson, Recollections, Political, Literary, Dramatic, and Miscellaneous, of the Last Half-century, Containing Anecdotes and Notes of Persons of Various Ranks Prominent in Their Vocations, with Whom the Writer was Personally Acquainted. London 1853; Thomas Allen, History of the Counties of Surrey and Sussex. London, I. T. Hinton and Holdsworth and Ball, 1829; Sholto Percy and Reuben Percy, London or Interesting Memorials of its Rise, Progress and Present State. T. Boys, London, 1824; Jeremy Bentham, Sir John Bowring, John Stuart Mill, The Westminster Review, Vol IX, Jan-Apr 1828. Baldwin and Cradock, 1828.

- The prison was often the scene of major disturbances: a mob tried to rescue the radical journalist John Wilkes from its walls in 1768, resulting in riots at St George’s Fields and the death of a spectator (the soldier who shot him was later executed); and the prison was burnt to the ground by Lord George Gordon’s anti-Catholic rioters in 1780.

- 3 October 1813.

- 12 June 1814.

Thanks for this vivid description. I’ve been trying to envision the life of a young fellow by the name of Robert Traill who was put to prison at King’s Bench for debts though he’d been a patient at Stratton’s Mental Asylum. An American caught in London during the War in 1782, he’d been abandoned by his father who was posted as Custom taker in Bermuda. Thomas Attwood Digges of Maryland had befriended Traill at Mount Coffee House, then a fashionable tavern of the day, and upon hearing a stray report of Traill’s incarceration corresponded in many directions in an effort to seek financial assistance for the chap whose manservant had abandoned him and stolen all of his clothing and goods.

Hi Steve – Yes, Georgian prisons were quite different to ours, although the profit model has certainly returned. Traill’s story sounds fascinating. Will you be writing it up? Naomi

Thank you for your interesting information about the King’s Bench, which I have just come across while researching the life of a relation, Sir John Powell Pryce 6th Bt., who died there in July 1776, most likely from typhus or ‘gaol fever’. He been accidentally blinded c.1761 by his wife Elizabeth, the daughter of Richard Manley of Careleigh Court, Berkshire and had been subsequently arrested for debt after having been plundered by his steward Francis Skryme, who had tricked Sir John into signing away his fortune and property in Wales.

In the prison his wife looked after him and after his death lived ‘within the rules’, dying in London in 1805, earlier in June 1791, their son Sir Edward Manley Pryce 7th Bt., who had been an officer in the 64th. Foot and later the 2nd Regt. of Dragoon Guards, was found dead in a field at Pangbourne and his body remained unburied for weeks, as no one came forward to claim it. In 1814 the remains of his son was discovered under the rafters in the house of Mr. Moreing, an undertaker, by Mr. E. Millward, a bricklayer a who was employed to repair the tilling. The coffin was found to have a note stating that this was Edward Manley Powell Pryce Esq., the only son and heir of Sir Edward Manley Pryce of Newton Hall, Montgomeryshire Bart., died on the 28th April 1788, aged five and a half years, the body having been left in safe keeping of Mr. Moreing until the family could afford to bring the body back to the family mausoleum at St. Mary’s Church in Newton, Montgomeryshire. Mr. Morley’s widow having then refused to to take further charge of the copse, the Vicar and Church wardens ordered it to be laid in a vault in St.Peters Church, Hammersmith.

Kind regards

P.S. In 1759 an English authority estimated that each year a quarter of the prison population died from gaol fever and it killed more prisoners than the hangman. Some prisoners that were brought before the court also infected members of the court, resulting in their death, in 1730 at Taunton and in 1750 at the Old Bailey.

What an amazing and awful story, Gerard, and a good example of how 18th-century fortunes plummeted in an eyeblink. Thank you for sharing it with us.