To state the obvious, rape trials in the Georgian era were stacked against the victim (plus ça change, I hear you murmur). The trial was all about her and what she did rather than what her assailant may have done. For any chance of success she had to offer the court specific proofs: that she tried to prevent the rape, that she cried out for help, that she fought back physically, that she tried to run away. The accused need not say anything, whereas any anomaly in her testimony could form a reason to acquit.

In law, whores were just as entitled to justice as the most spotless of virgins. In practice, the victim generally needed to show that she was a paragon of virtue.

Rape was a capital crime, and there was always a chance a convicted rapist would be executed (although this was more usual for the rapists of children), which gave juries a moral dilemma. They simply did not see rape as deserving of death, and were often reluctant to convict for that reason.

On 11 September 1785 20-year-old Catherine Wade was raped after being dropped off by a friend near her residence in Brighton.1 She was a particularly vulnerable victim – as the prosecution barrister Thomas Erskine said at the trial of her attacker, ‘Nature had not endowed her with a strong understanding.’ She had been brought up in a convent in Calais, had only recently arrived back in England and was innocent about the world. In the words of her father, the master of ceremonies at Brighton, she was ‘unaccustomed to the deceits in the busy world.’2

Brighton Beach Looking West, John Constable (unknown date). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection].

Catherine had spent the day with her friend Elizabeth Hart and Hart’s mother Lady Hart. During the evening, on a very wet and stormy night, she was taken home by another guest, Mr Griffiths, a surgeon, but the street where the Wades lived was inaccessible to carriages and she ended up walking up the steps and along the passage to the door alone. There she was seen by John Motherhill, a poor tailor, who started to engage her in conversation and then put his hand on her bosom and up her petticoats. He insisted that she go with him, walking down the passage behind her. It is difficult to know whether she tried to scream. If she did, no one came to her aid because the weather meant there was no one about.

They went into a graveyard, where Motherhill raped her three times, afterwards dragging her to the beach and into a bathing machine where he raped her again. In the morning, as the water rose, she remarked that the women would soon be coming to use the machine, he led her out and let her go.

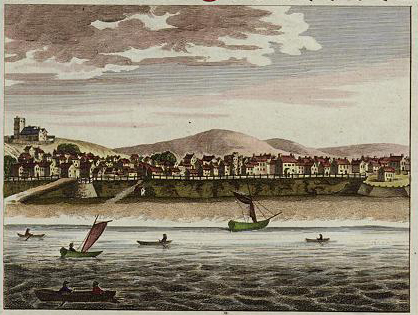

Detail: Brighton from ‘Brighthelmstone” and “Chichester’, anonymous, published in New and Complete English Traveller about 1784. Courtesy of ancestryimages.com.

Catherine’s father was frantic with worry and spent the night looking for her, joined at daylight by volunteers, one of whom arrested Motherhill after he was seen following Catherine. Motherhill more or less confessed – ‘I have been a very wicked wretch, and have deserved to be hanged a long time.’ – and was committed to Horsham Gaol. Catherine arrived home in a shocking state: bruised, dripping wet and filthy. She was put to bed and her life was thought to be in danger.

However, within hours, poor Catherine had to submit to an intimate examination by two male surgeons. At the trial on 21 March 1796 at East Grinstead in Surrey both surgeons gave evidence that she had been ‘violated’ and one suggested that if Motherhill had been suffering from a venereal infection, she was unlikely to catch it because she was in a ‘state of natural evacuation’.3 In fact, he was found to have a ‘gleet’, a discharge caused by gonorrhoea.

Bathing Machine on the Common, near Southsea Castle, 1788, John Nixon. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Catherine gave evidence but became confused under cross-examination by Mr Rous,4 who asked why she had not cried out when Motherhill forced her along the passage by her door (she said it was ‘fright’ – not an adequate reason in a rape trial), and did not run away or knock on doors and windows when they walked along North Street. Rous also pointed out that when they reached the bathing machine, Motherhill led Catherine up the stairs by the hand – proof that he did not force her. Motherhill’s defence was that he mistook Catherine for a woman of loose morals, of whom there were many about.

Despite Catherine’s mistakes, the jury was minded to convict. They conferred for half an hour, but then asked Judge Ashurst a question. Was there no alternative between death and acquittal? None, said the judge and so, after a further few minutes, they returned a verdict of Not Guilty.

- At that time known as Brighthelmstone.

- Anon. (1796). The Trial of John Motherhill, for the Rape on the Body of Catherine Wade. London: E. Macklew.

- It must have been so much fun to be a Georgian surgeon: you got to make stuff up for the hell of it.

- Probably George Rous.

Leave a Reply