A guest post by Mike Rendell, whose recently published In Bed with the Georgians: Sex, Scandal and Satire in the 18th Century (Pen & Sword), is a handsomely produced large format paperback, packed with colour illustrations and fascinating information. I’ll be reviewing it on the site soon.

A guest post by Mike Rendell, whose recently published In Bed with the Georgians: Sex, Scandal and Satire in the 18th Century (Pen & Sword), is a handsomely produced large format paperback, packed with colour illustrations and fascinating information. I’ll be reviewing it on the site soon.

Mike’s blog grew out the work he did for his first book, The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman, which drew on the huge volume of 18th-century papers he inherited from his 4 x great-grandfather, who had a haberdashery shop on London Bridge and later retired to the Cotswolds to become a farmer.

Follow Mike on Twitter @GeorgianGent

So, without further delay, here is Mike on the rollercoaster fortunes of the heiress Catherine Tylney-Long, who made a catastrophic decision which affected her whole life thereafter.

One of the things which amazed me when doing the research for In Bed with the Georgians was the incredible wealth – and naïvety – of some of the 18th-century heiresses. Catherine Tylney-Long was a case in point.

Catherine Tylney-Long and William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley

She first came to my attention because when this double-barrelled young lady married a scion of the famous Anglo-Irish Wellesley family, and her husband adopted her surname in addition to his own, becoming known as the Rt. Hon. William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley.

A handy little moniker if ever there was one! At 21, Catherine was attractive, lively and petite, but above all, she was loaded. She had inherited a vast fortune at the age of 16, estimated at giving her an income of £40,000 a year – and had spent five years trying to avoid fortune hunters. She then made the biggest mistake of her life, by marrying a man who would turn out to be one of the most profligate and odious men of the century. He was a nephew of the Duke of Wellington, and was reputed to have been turned down on the six previous occasions when he had proposed marriage to her.

The Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence

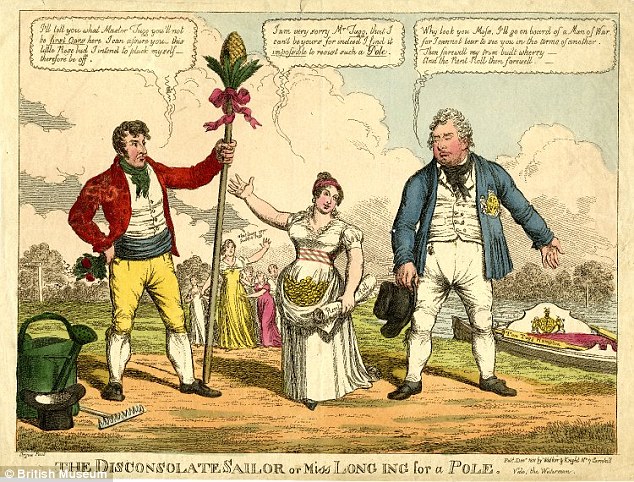

Unfortunately for her, her resilience failed her and she finally consented at the seventh time of asking. She had other suitors – notably the Duke of Clarence (later to become William IV) and cartoonists revelled in the Duke’s embarrassment at being spurned in favour of the Irish ne’er-do-well.

Caricature of the Regent and William – courtesy of the British Museum

The newspapers had a field day when the marriage took place in Piccadilly on 14 March 1812, reporting that after the ceremony ‘the happy couple retired by the southern gate… where a new and magnificent equipage was waiting to receive them. It was a singularly elegant chariot, painted bright yellow, and highly emblazoned, and drawn by four beautiful Arabian grey horses, attended by two postilions in brown jackets, with superb emblazoned badges in gold, emblematic of the united arms of the Wellesley and Tylney families. The newly married pair drove off, with great speed, for Blackheath, intending to pass the night at the tasteful chateau belonging to the bridegroom’s father, and from thence proceed to Wanstead House, in Essex, on the following day.’

Newspapers then, as now, seemed to concentrate as much on what everything cost as on what the bride wore. The same report advised that ‘The dress… consisted of a robe of real Brussels point lace… placed over white satin. Her head was ornamented with a cottage bonnet of the same material, being Brussels lace with two ostrich feathers. She likewise wore a deep lace veil and a white satin pelisse trimmed with swansdown. The dress cost seven hundred guineas, the bonnet one hundred and fifty, and the veil two hundred, and she wore a necklace which cost £25,000.’

If the day was the happiest of her life, things started to go downhill with ominous speed. No sooner had he had got his hands on his wife’s money than William spent it with extravagant zeal. There were ostentatious parties at the family home at Wanstead which cost a fortune – and from which Catherine was excluded. And then there was the constant and unbelievably reckless gambling, on top of which vast sums were laid out in bribes to get William elected to Parliament. It was also decided to refurbish Wanstead, a magnificent Palladian mansion, at an estimated cost of £360,000. The papers reported that the couple were ‘fitting up Wanstead House in a style of magnificence exceeding even Carlton House.’

Assembly at Wanstead House by Hogarth

In the course of a decade Catherine had to suffer in silence as her husband spent her entire fortune, forcing the couple to flee abroad to avoid their creditors – humiliating for a woman who had been given the accolade of being the richest woman in the land just ten years earlier. Worse humiliation followed when they reached Italy – William openly conducted an affair with one Helena Bligh, the wife of a captain of the Coldstream Guards. Catherine tried, unsuccessfully, to buy off her rival but, realising the futility of the exercise returned to Britain with her three children, determined to obtain a legal separation from her husband. Meanwhile Wanstead house had been put up for auction – the entire contents were sold but the house failed to attract a buyer and had to be sold ‘one stone at a time.’ The proceeds amounted to a miserable £10,000. William accepted no blame at all for the extravagance which cost his wife her entire fortune, always claiming that it was ‘someone else’s fault.’

Her health broken, Catherine died at the age of 35, entrusting the care of her children to her two sisters. Her death may well have been attributable to a nasty dose of the clap which her husband gave her, as there were indications that she developed an inflammation of the bowels caused by a venereal disease. A letter to one of her sisters hints at this. Her death triggered a series of legal battles in which William tried to recover legal custody of his children.

Astonishingly for the time (when, as the natural father, he would always expect to be supported by the courts) his case in Chancery failed – over and over again. Each case brought further salacious details of William’s private life into the public domain. In particular he openly lived with Helena, his mistress, and when she came to live in London her husband Thomas Bligh decided that enough was enough, and he brought a suit of ‘crim.con.’ against William. The public revelled in the gossip, and cheered tumultuously when the court awarded damages of £6,000 to the cuckolded husband. William retaliated by publishing accounts which sought to defend his adulterous behaviour, and heaping accusations of immorality on to the two Long sisters who had been given legal custody of the children.

In November 1828 William married Helena, who by then had, in the minds of the general public, been exposed as a whore. It was a disastrous second marriage, and before long she was reduced to claiming poor relief from the parish. William eked out the last 30 years of his life in considerable poverty, dying in July 1857 while eating a boiled egg. The Morning Chronicle published an obituary which described him as ‘A spendthrift, a profligate, and gambler in his youth, he became a debauchée in his manhood… Redeemed by no single virtue, adorned by no single grace, his life has gone out even without a flicker of repentance…’

It has to be said: the boiled egg did the world a favour!

She didn’t marry the Duke of Clarence because of his age, his numerous children by Jordan and the Royal Marriage Act. Of course, her case gave cause for fathers and guardians to use her as an example of why young ladies needed to have wiser masculine heads work out the marriage settlements and put things in trust. I believe her bankers did what they could but that the husband ignored such legalities and that some of the court cases were about his committing waste. Truth is indeed stranger than fiction. Few readers would accept such a story.

She was obviously sensible to turn down the Duke of Clarence – for the reasons you mention – but nowhere in her wildest dreams would she have imagined that her husband would turn out to b such a boorish wastrel.

The court cases show that the children were regarded as “possessions” – no-one actually considered what was in their best interests.