Today was spent in the British Library, where I came across this remarkable broadside on the extraordinary execution in 1826 of a young woman called Elizabeth Simmonds. As I had never previously heard of this person, I was immediately intrigued…

On Monday last, March 6, 1826, was Executed, pursuant to sentence at Aylesbury, Elizabeth Simmonds, for the Wilful Murder of her new-born male child, She is the daughter of wealthy parents, and was born at West Harptree, in Somersetshire. In or about the 6th year of her age, she left her parents and resided with a near relation at Bath, under whose care she remained about four years, when it was considered expedient to send her to a boarding school at Langford, in Somersetshire, where she received, not only a grammatical English education, but was also versed in the Latins and French.1

The information is very specific. West Harptree is a tiny village eight miles south of Bristol with a population in 1810 of around 350 according to the Vision of Britain website. The current population is about 440.

West Harptree, Somerset © Copyright David Gearing and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Langford, 12 miles south west of Bristol, is another small village.

Here [at Langford, Somerset] she remained till she had attained the age of seventeen, and being of a very gay turn and have a prepossessing countenance, several respectable young gentlemen courted her acquaintance with a view, at some future period, of obtaining her hand in marriage…

Then poor Elizabeth’s life starts to go horribly wrong.

…amongst whom was a young gentleman named Jackson, who after various artifices seduced, and afterwards, deserted her. Finding herself in a state of pregnancy, she left her tutoress, and although the strictest search was made for her she eluded every pursuit. Becoming now quite careless of herself, she wandered from place to place until she arrived at Aylesbury, where she attracted the attention of a young man who is a clerk in a respectable Banking house, who from her very graceful demeanour fell passionately in love with her, and at length a day was appointed for the celebration of their nuptials, he little suspecting she was at that time in a state of pregnancy; and she, willing to embrace the opportunity, kept the clandestine affair so secret that no one of her acquaintance had the least item of it, until about three months since, an elderly lady who occupied an apartment on the same floor with that of Miss Simmonds, about 4 o’clock in the morning, heard the cry of a child; however, she remained in bed till about eight, when she imparted the news to some of her neighbours, who without ceremony went into Miss S’s apartment and stated what they had heard. She, however, positively denied the charge; but upon investigation they discovered a new born male child under the bed-clothes, with its neck writhed. She immediately confessed the face, and was fully committed upon her own evidence. She was tried and received sentence on Thursday, March 2, and executed on Monday the 6th.

Awful, but there’s a dramatic postscript.

After hanging the usual time the body was cut down and delivered over to the Anatomical Surgeons for dissection, who had proposed the process of and giving a lecture on Galvinism [sic], and the unfortunate female was stripped and put in a proper posture for the operation; when symptoms of animation was observed by one of the faculty. Restorative means were resorted to, which at length proved successful, and incredulous as it may appear, we have been given to understand that she is in a fair way to recovery.

This was an extraordinary event, but not without precedent. Occasionally, slow strangulation on old-style gallows would not succeed in completely ‘turning off’ malefactors. For example, in 1740 the body of 16-year-old rapist-murderer William Duell was taken to Surgeon’s Hall, where he showed signs of life. He was revived and sent back to Newgate but his sentence was commuted to transportation.

Condemned criminals had a horror of waking up after hanging to find themselves being dissected. It was one of the reasons their friends pulled so hard on their legs after they were launched. Conversely, the corpses of criminals were believed by many to have special healing powers and some surgeons were of the belief that hardened criminals were physically more resistant to hanging.

Henry Hollings was hanged at Newgate for the murder of his stepdaughter on 19 September 1814. According to the Newgate Calendar, three women asked to receive a touch from ‘the dead man’s hand,’ which was believed to remove birthmarks and wens.

Surgeons were also horrified at the thought of anatomising a live person and before they started performed tests to ensure that the executed person was well and truly deceased. William Clift, who carried out the dissections at the College of Surgeons, described inserting needles into the eyes of one corpse of Martin Hogan in 1814, but there were less gruesome methods: putting a hot wet cloth on the face and tracing a swan’s feather along the neck. If there were no signs of life, a small cut was made at the breast bone so that the surgeon could observe the heart and lungs. If blood was still flowing, he would wait until life signs stopped.2

The trouble was no one was quite sure when the moment of demise took place. Perhaps there was state somewhere in between life and death. In 1817 James Curry, a physician at Guy’s hospital, wrote a book that gave information on how to distinguish ‘absolute’ from ‘apparent’ death. Among his patients were the poet Shelly and his wife Mary, the author of Frankenstein, which she started writing in 1816 and published in 1818.

James Curry (1763-1819), Physician at Northampton General Infirmary (1791-1793), later physician to Guy’s Hospital; Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/james-curry-17631819-md-physician-at-northampton-general-infirmary-17911793-later-physician-to-guys-hospital-49370

It is interesting that the account of Miss Simmonds’ non-execution mentions that the surgeons were about to give a lecture on galvanism. Life forces was a popular subject, which exercised some of the best minds, both scientific and creative.

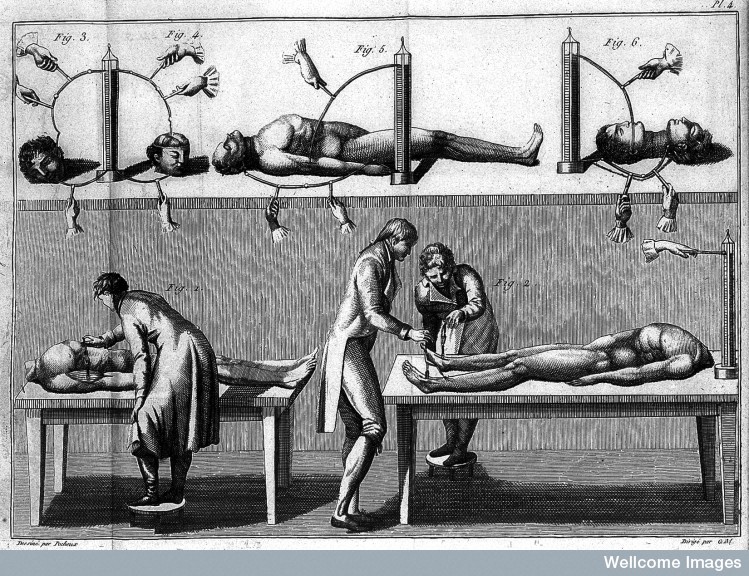

Giovanni Aldini’s galvanism from Essai theoretique experimental sur le Galvanisme (1804). Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

The term galvanism derives from Luigi Galvani’s experiments on frogs’ legs, which twitched when struck by an electric current. Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, took things a step further and on a visit to London in 1803, as a guest of the Royal College of Surgeons, he galvanised parts of the executed corpse of George Forster, who had been executed for murdering his wife and child. Apparently, Forster’s eye opened, his right hand was raised and clenched and his legs moved. The judicial authorities were probably not keen on these experiments, as the point of giving the corpses of executed murderers to the surgeons was so that they would be mutilated to the point of non-existence, not so that they could enjoy a second spark of life.3

The process of dissection destroyed the remains of the corpse, usually over a period of three days, during which various groups would be invited to pay to watch the anatomisers at work. Business-minded surgeons could make a good profit from the corpses they received. On the first day the paying public, labouring people of both genders, filed past the corpse, either to see it being opened or to look at it prone with the first cuts made. When Dr Hey exhibited the murderer and so-called witch Mary Bateman at York in 1809 he raised £30 by charging 24,000 3d (threepence) each. Later in the day, medical students, each paying 1s and 6d, arrived to witness the first phase of the dissection.4

On Day 2 the educated elite or professionals of the town (men only) came to see the spectacle. They might pay as much as five guineas to watch a post mortem dissection of muscle tissue, for instance. That evening, ladies could observe the dissection of an eye. This was deemed suitable for their genteel sensibilities as, unlike the women of the labouring poor, they were not allowed to see naked body parts.

On the final day, the medical men and their apprentices would watch the full-scale dissection, which concluded with a complete dismemberment of the body. The brain would be preserved and the bones sent to be wired into a skeleton for use in the instruction of medical students. Other body parts might be sold for exhibition in museums.

It was certainly fortunate that someone noticed signs of life in Elizabeth Simmonds before an incision was made. Or was it? I looked for Elizabeth in the British Newspaper Archive. Nothing. The online parish clerk for West Harptree had no entries for a family of the name Simmonds. My suspicions, already raised by her very unusual story, were now on full alert. There were no entries for her in the Criminal Register. I think we have to accept that she never existed and that the story of her sad end on the scaffolds and subsequent resurrection was a hoax.

Why would a broadside printer publish such a thing? As the places named are so specific, and so small, I can only think that he had someone in mind for an elaborate joke. If it is a fiction, it would not be the first. I have come across other broadsides that seem to have no basis in real events. These, listed in the Borowitz collection at Kent State University, are under suspicion:

A full and particular account of the confession and dying words upon the scaffold, of Elizabeth Robinson. Midwife, aged 50, who was executed at Essex, on Tuesday, the 28th November, 1820, for the murder of Margaret Thomson and her child in her delivery.

An Account of the execution of Margaret Harvey (‘a young woman of only 18 years of age, who was executed at the New Drop, London, on Monday the 8th of January, 1821, for the murder of her male bastard child.’)

If anyone can shed further light on Elizabeth Simmonds or the two cases above, please leave a comment.

POSTSCRIPT (17 June 2016)

Two earlier (and documented) cases of revival after hanging:

1650 Anne Greene executed at Oxford for infanticide.

1727 Margaret Dickenson at Edinburgh

The London Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. 8

- An Account of the Execution of Elizabeth Simmonds, who Suffered the Extreme Sentence of the Law at Aylesbury, on Monday last, March 6, 1826, for the Murder of her New Born Male Child, and who was Restored to Life Again, having been Cut Down and Delivered to the Anatomical Surgeon for Dissection (Bristol: M. Shepherd, [1826]). British Library shelfmark 1880.c.20 (459).

- Hurren, E. (2013). The dangerous dead: dissecting the criminal corpse. Lancet, 382, pp. 302-303.

- Giovanni Aldini, General views on the application of galvanism to medical purposes (1819).

- Hurren, ibid.

Leave a Reply