Karen Robinson, co-founder of the Times’ Crime Club, puts some questions to Naomi Clifford about her new historical crime novel 13 Park Lane.

Naomi Clifford has made her name as a writer of non-fiction, uncovering and bringing to light real women’s stories. The Times Literary Supplement praised her alert analysis of and sensitivity to contemporary Georgian attitudes in Women and the Gallows; and a more coherent and articulate than usual Amazon ‘reviewer’ opined that ‘Her style is as readable as her research is thorough’. An opinion any of us who have read her books will heartily endorse.

But Naomi’s latest book, 13 Park Lane, is a big change of direction – it is a novel, and a crime novel at that. And a leap forward from her beloved Georgians.

It’s 1872, and in London’s aristocratic Mayfair, a French woman, a former Parisian milliner with a glamorous actress daughter, takes in a young Belgian refugee as her cook. But all is not well behind the stucco façade.

Karen Robinson

- So let me ask you, Naomi – where did you find this story?

I regularly trawl the indexes of files in the National Archives looking for possible stories and and came across a 19th-century case where both the victim and protagonist were women. This was an unusual scenario in itself, but here both had non traditionally English names, so I decided to delve into the case a little further.

What I read about it was quite tantalising and I could see that there were no major works on it, apart from a book written in French by a distant cousin of the protagonist, Marguerite Diblanc. I pulled out the newspaper reports of the case, which indicated that Marguerite had lived through the Siege of Paris and fled the subsequent Commune de Paris. I went to the National Archives at Kew to read the file on the case which included various gems such as a wanted poster for Marguerite.

- The late Victorian period is not your usual era – most of your books have been set earlier, in the Georgian period. What was it about Marguerite’s story that encouraged you to leave your favourite era?

There was so much in the story that resonated or that I felt would resonate with readers: trauma, food, bad employers, snobbery, child loss, the agency (or lack of) of women, with plenty of potential for drama and tension. The story was simply too good an opportunity to pass up.

Of course, history is a continuum and underlying social attitudes, especially towards women, had not changed in essence, and in France were much more extreme than in Britain. The challenge for me now was to bring an understanding of women’s lives through the story of Marguerite and the other characters in the book.

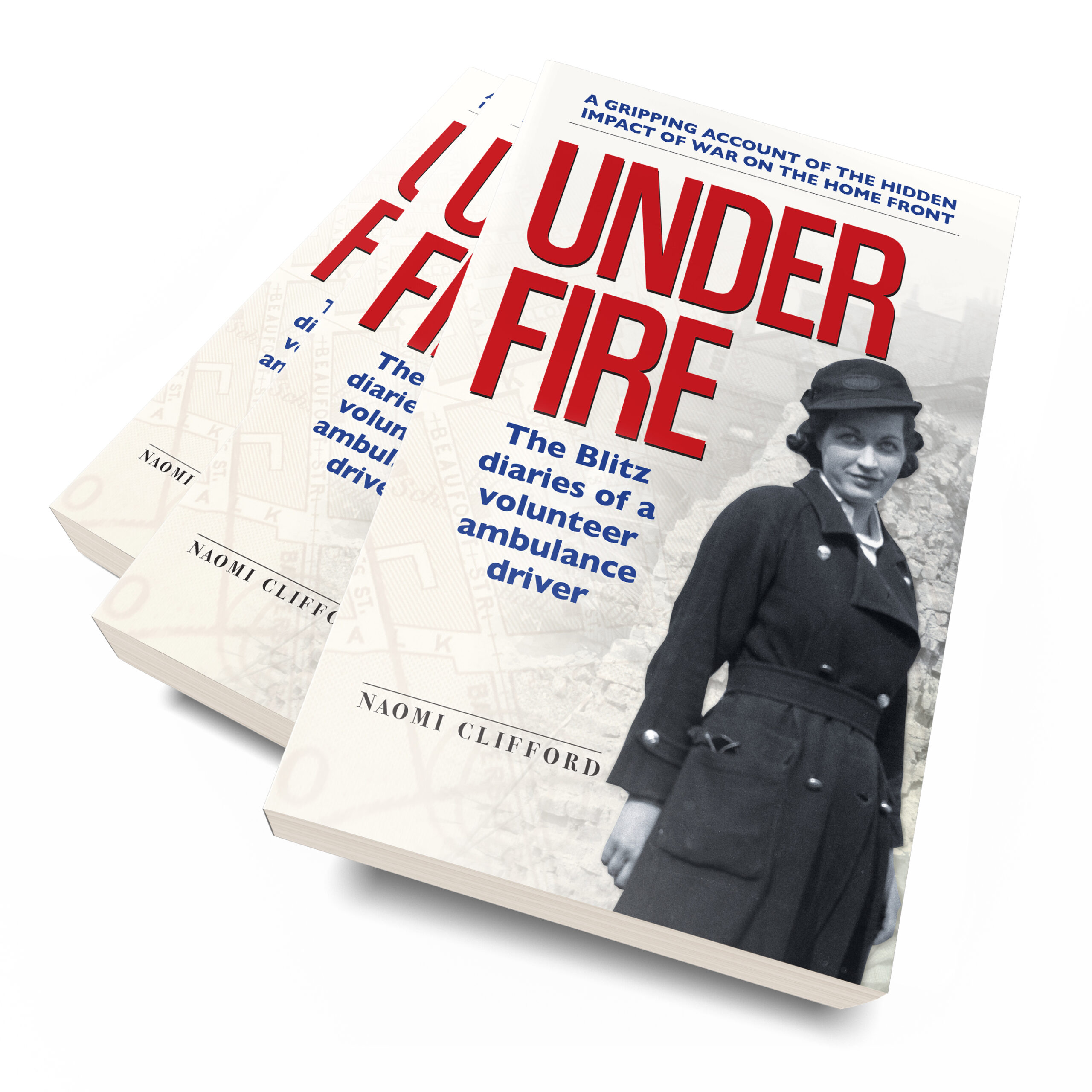

I have left my beloved Georgians before – when I wrote Under Fire, The Blitz Diaries of a Volunteer Ambulance Driver which uses the journal of June Spencer to tell the story of the ‘forgotten service’.

- When did you realise you wanted to add a helping of creative imagination to your factual research and turn it into a novel?

I made that decision to switch to fiction really when I reached a dead end in the research. There were vast swathes of the story that were impossible to progress because they were unknown. Of course, as in any good non-fiction, a writer can intelligently guess or make a case, but for this subject that would have left me with a narrative that felt, to me, incomplete.

The extent of the involvement of the George Bingham, Third Earl of Lucan, for instance, is difficult to assess without proof. There is some scant evidence that his lawyers helped suppress reports about his relationship to the women living at 13 Park Lane, although not enough to be sure. And there is also the question over whether it was Madame Riel or her actress daughter that interested him. The handful of writers who have covered the facts of this case have concluded that because he was an elderly man at the time of the murder that it must have been Madame Riel, who was in her forties and therefore closest to him in age. My belief is that this is wrong and I have evidence to support it.

I also had difficulty tracking Marguerite’s life in Paris through the Siege and the Commune. After the murder, she was accused of being a Communarde, for which there was no evidence. However, many records went up in flames at the end of the Commune so again, it is difficult to prove. Both she and her priest were adamant that she had no involvement in politics, which is not to say she could not have been swept up in the fast-moving political events of the time.

So for these reasons I came to understand that the only way I could tell the story in a coherent way was through fiction.

After several attempts it realised that I didn’t have a clue how to write a novel, so I took a course at CityLit, taught by Sarah Leipciger. Her teaching and the feedback proved invaluable.

- It’s a novel but you also did a lot of research, in more than one country, as the end notes of the book make clear. What advice would you give to writers juggling the narrative with context in historical fiction? How should they avoid giving history lectures in their manuscript?

It’s the characters who tell the story, of course, and the characters will behave as people do in any era of history. So historical events should not take over from the characters. They can be more than background but they should not be introduced unnecessarily.

Because the book is written from Marguerite’s point of view, I had to put myself in her shoes. She started life far down the social ladder; she was a working-class woman. She would not have participated in much of the political activism of the Paris Commune, for instance, but she would certainly have witnessed some of it.

To describe Marguerite’s life in Paris before she fled I took inspiration from accounts written by people, especially women, at the time, and adapted them to fit Marguerite’s life. Also I looked at the work of the Communards who had fled to London. Jules Vallès, for instance, escaped France by the skin of his teeth, and lived in London but HATED it. Luckily for me, he wrote about it. He viewed London as an outsider, just like Marguerite, so I took some of his words and put them into Marguerite’s mouth.

When writers write about past times they bring a contemporary sensibility to their work. While I strived to find themes that would interest my potential readers, I was also aware that I should remain historically accurate as far as I was able. Of course, I was peering back at the past from a distance of 150 years. Things have changed. What preoccupied people then was not necessarily what we want to read about now.

- Though the book is set in London, many of the characters speak mainly or only French. How did you decide to tackle the writing of the dialogue and Marguerite’s inner monologue?

At the time of the crime, Marguerite spoke no English. She communicated with the other maid at 13 Park Lane, an English woman who spoke no French, through signs and a handful of shared words. To describe their form of communication I wrote it as a kind of playscript, including gestures and indications to the reader of what each thought the other was trying to convey.

A particularly problematic area was the trial, where the proceedings were in English although the spoken evidence was translated for Marguerite by a court-appointed interpreter. However the barristers’ opening and closing speeches were not translated, nor were the remarks of the judge. So the challenge was to get the reader to understand how much of the trial Marguerite could keep up with.

- 13 Park Lane was published in October 2024 in paperback, ebook and audio. So what’s next for you?

I am working on another real London murder in the late Victorian era, with another female protagonist. I can’t say more than that at this stage.

- Was it hard to switch from the strictly factual to fiction? How did you work out how to do it?

It was certainly a big leap, and the CityLit course and the writers’ group we set up afterwards was hugely helpful. I had many new skills to learn and the fiction muscle needed building up. I could not have finished the book without them. I also had fantastic help from the annual Cheshire Novel Prize, which I provided practical feedback on my submission, especially on how to restructure the book.

- How did you get a publisher?

I tried very hard to get an agent but it was taking too long (I am quite impatient), so I started to look around for publishers who accept unagented manuscripts. Among these was Bloodhound Books, who specialise in crime novels. I sent it in and they responded within a week to say they wanted it. I have been absolutely thrilled to join their stable of authors.

Leave a Reply