Before the days of mechanical brushes there can have been few occupations more cruel or hazardous than chimney sweeping. The job entailed climbing into tiny, hot, soot-filled spaces. It goes without saying that children were ideal for this, and the more diminutive or stunted the better.

They worked in almost unbelievable conditions, at the mercy of their masters, who were often brutal in the extreme. It was not unknown to light fires while the boys were in the chimney to encourage them to go on up to the top. The plight of the chimney sweep apprentices was a scandal noted by philanthropists and by ordinary people, but it was a scandal with little remedy. Nearly all buildings had chimneys – and they all needed sweeping. Someone had to do it.

The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album. Arranged by James Montgomery. Illustrations by George Cruickshank (1824)

In 1788 Jonas Hanway and others tried hard to improve things. They started a subscription for the apprentices and tried to get a bill through Parliament that would protect the sweeps from the worst abuses. Although it was passed, it lost the more effective clauses on its passage through the Lords. 1 A Friendly Society for the Protection and Education of Chimney-Sweepers’ Boys was established in 1800.

Samuel Jackson Pratt, in his Gleanings in England, (1803)2 described seeing chimney sweeps in St Martin’s Lane, London as “a race of beings too suffering to be passed over in the moral tour of the metropolis.” They were “melancholy both to see and to hear.” They slept, he said, in unheated cellars, often in sacks, using their soot cloths for blankets.

From these dreary and miserable abodes, chilled with cold, the poor infant is dragged from his comfortless cell, to endure the inclemency of frost and snow; half naked he trudges along the streets, shivering with cold, several hours before he is cheered with the light of day…Their bodies are doomed to suffer misery in the extreme, while their minds are exposed to every thing that can render their wretchedness compleat.

The boys Pratt saw were brothers aged six, seven and nine, who worked for their father. The elder boy told him that they were starved and beaten, and damaged by the soot “that has almost eat into my flesh.”

Pratt calculated that there were 200 masters and 500 apprentices operating in London, of which only 20 masters were “reputable tradesmen”.

The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album. … Arranged by J. Montgomery

While trawling The Observer (1817), I came across a moving account of an inquest into the death two days previously of 14-year-old orphan Robert Dowland, who died of suffocation in a bakery chimney in Somers Town.

There were two chimneys to clean. During the first climb, Robert was injured by nails and cried piteously. He went up the second flue and became stuck. Alexander Bishop, the baker, described events:

Hall [the master], Mrs. Bishop [the baker’s wife], and the landlord of the public house were in the shop when he went in. They told him a boy was in the flue; he asked the master how long; he said an hour; witness said, “My good God! why don’t you break down the flue and run down to the bakehouse?” Got a poker, Hall followed him, and said he was too hasty: witness put his head up the chimney, and could hear the boy breathing hard; took the poker up stairs, and began to break open the flue; in a moment he had room to put his hand in, and cleared away the soot from his [Dowland’s] head; held it up, but seemed not to have life in it. He went down stairs and broke the flue below, and got at his feet: when the master saw that, he said, “Let me get at him, and I will get him down, as he is only sulky, and is taking a nap.” Mr. Smith then came and made a greater aperture above, and he and witness lifted him out.

Although the boy was still alive, just, he could not be saved. He had been cooked – his flesh was hot – but the medical opinion was that he had suffocated. The coroner’s jury viewed the body, which was now “very much swelled,” and delivered a verdict of death by culpable neglect of the master. I was particularly struck by the evidence of 13-year-old Richard Barry, who would not speak against his master. For these boys, the life they had was all they had.

I have transcribed the entire report. Grim but worthwhile reading.3

- Read more about legislation and chimney sweeps at Parliament UK.

- Gleanings in England; Descriptive of the Countenance, Mind and Character of the Country, with new views of Peace and War. London, T. N. Longman. Vol 3. Pratt (1749-1814) was a poet, dramatist and novelist, often writing as Courtney Melmoth.

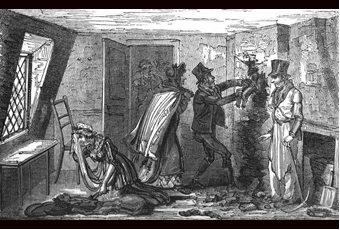

- In 1824 James Montgomery published The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album, an anthology of poems, as part of a campaign to abolish the use of children in the cleaning of chimneys. It includes ‘The Chimney Sweeper’, one of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence. The illustration, which shows a boy being taken out of a flue, is by George Cruickshank and comes from that book. More information at British Library.

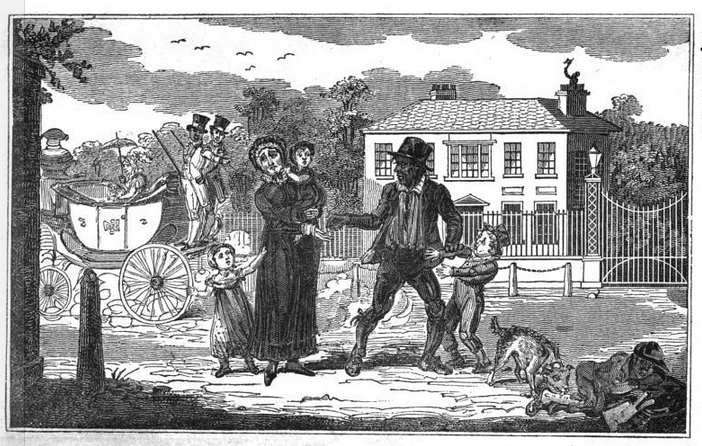

In the engraving showing the distraught mother selling one of her children to the master sweep, the dog at bottom right is licking the sores of the exhausted climbing boy, a telling detail.