A black nursemaid cares for Elisabeth, Sarah and Edward, the children of Edward Holden Cruttenden. Joshua Reynolds, 1763

Mary Ann Whitby was only 13 when she arrived to take on duties as a nursemaid in the household of the Tucketts, a unostentatious middle-class household in Taunton, Somerset. She is one of the main protagonists in my non-fiction book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn (Pen & Sword, 2016). She was from a poor but respectable Dissenting family and was literate.

Mary was hired to look after the three young daughters of the family and to help Maria, their 15-year-old niece, to dress and undress (ties and buttons made it was next to impossible to do this oneself). A maid and a cook also worked for the family, but there were no male servants, nor a governess. The family’s three boys were away at boarding school and the eldest daughter and the niece attended a day school in Taunton.

We do not know Mary Ann’s specific duties but we can draw a picture of her life from clues in the records, and from other sources, particularly The Complete Servant by Samuel and Sarah Adams, which describes in detail the responsibilities of servants1. The focus is on servants working in grand households, but we can extrapolate from this what Mary Ann’s life may have been like.

Mary Ann would have had to bathe the children, prepare their breakfast and take them for a walk, if the weather was good, or take them to school. She would have had to ensure their hands and feet were clean when they returned to the house for dinner (which was served in the late afternoon). She may have had to take them out again after dinner and then prepare them for bed. She ensured that those beds were clean and dry and that their chambers were well ventilated (the Georgians were obsessed with air quality and believed that bad air carried disease). She had to make or at least maintain the fire.

Children had high rates of mortality, and parents and servants were on the constant look-out for symptoms of disease. Indeed, almost immediately after Mary Ann arrived in the household, two of the Tuckett daughters and Maria were struck down with whooping cough.

The recommended treatments for whooping cough included a daily warm bath (Mary Ann and her fellow servants would have had to heat and transport vast quantities of water on the range for this), bleeding (done by a doctor) and cupping. Emetics may have been administered as it was thought that vomiting gave relief. The recommended recipe included potash, liquorice, foxglove, almond emulsion and gum arabic. Mary Ann may also have rubbed the children’s chests with an embrocation made of emetic tartar, tincture of cantharides (Spanish fly, a blister-inducing beetle) and oil of wild thyme. Bizarrely, sea voyages (short ones, anyway) were thought to bring benefits.

It is likely that Mrs Tuckett took charge of the children’s care, with Mary Ann doing the fetching and carrying: cold compresses, clean linen, chamber pots, and food from the kitchen. Mrs Tuckett herself suffered from chronic ill-health of an unspecified kind, so Mary Ann’s help here would have been crucial. Mrs Tuckett simply could not manage on her own. That Mary Ann did not succumb to such a highly infectious disease indicates that she may previously have been exposed to the virus and therefore was immune.

Sara Hough, Mrs. T. P. Sandby’s Nursery Maid by Paul Sandby, c 1805. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

When it was apparent that the children would live, they were sent to Holway Green, a farm just outside Taunton, to recuperate. Mary Ann accompanied them. Her new duties included walking back to the house to collect meals specially prepared by Mrs Tuckett, as well as her own ‘work’ (needlework and mending), at least on the days that the parents did not visit and bring vittles with them. She shared a room at the farm with her charges, a not uncommon practice in this period. Servants routinely slept in their employers’ bedrooms where houses were overcrowded or when the male head of the household was away (it felt safer that way).

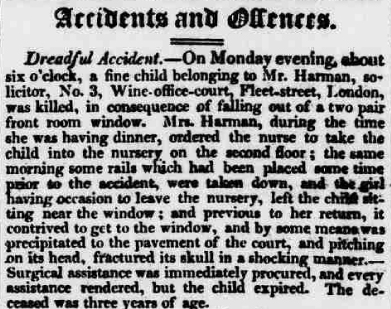

Apart from watching for disease and sickness, Mary Ann would have been tasked with guarding the children against the dangers of the house, especially in the kitchen. The newspapers of the time were littered with reports of “Melancholy accidents,” where children had become impaled on lethal implements or had fallen into open fires or out of windows.

Leeds Intelligencer, 19 July 1819. Image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved.

While the children were asleep Mary Ann would have cleaned her charges’ shoes and laundered and pressed their clothes. At bedtime, she helped Maria out of her frocks and stays.

Domestic staff did not wear uniform until the mid-19th century. Employers donated their cast-off clothing and it is likely that Mary Ann wore Maria’s old frocks. Indeed, there was a claim that she was mistaken for Maria while walking through the town on her way to collect the daily food. The scandal in which Mary Ann became embroiled turned on the issue of mistaken identity and impersonation, and clothes were crucial elements in the mystery of what happened to Maria after her summer at Holway.

A Nurse with Three Children by Paul Sandby, c 1800. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

In return for all Mary Ann’s responsibilities and duties, including taking sole charge of the Tuckett daughters at the farm and acting as an informal chaperone to Maria, she might expect to receive between seven and ten guineas a year (£7.30 to £10.50) plus her bed and board, but possibly less because she was so young.

What is perhaps surprising is that through the traumas that followed that stay on the farm – court cases, scandal and loss of reputation – Mary Ann and Maria became good friends. The Tucketts told Mary Ann’s parents that they were prepared to treat her as their own and to spare nothing to defend her in the courts. As it turned out, a huge betrayal was to divide the girls for ever…

Leave a Reply