Six days after her capital conviction for a creative fraud that, had she been successful, would have netted her £500, 22-year-old Ann Hurle was brought back into the Old Bailey courtroom with six others who had been similarly condemned to receive sentence. She was terrified and fainted twice.

John Silvester

John Silvester, the Recorder of London, asked her if there was any reason the death sentence should not be pronounced on her.

Anne Hurle, on being asked why sentence of death should not be pronounced against her, said, that she thought she was with child. This, however, was not asserted with sufficient confidence to occasion any enquiry. Sarah Fisher, another of the prisoners, alleged with confidence, that she was with child; this occasioned the calling of a Jury of Matrons, who, after retiring to another apartment, declared, on oath, that she was not quick with child. She was accordingly taken back to prison, to suffer the punishment to which she had been sentenced.”1

The usual practice when a condemned woman “pleaded her belly” was for the court take steps to determine whether she was telling the truth. The underlying principle was the protection of the unborn child, but there were important restrictions on the definition of pregnancy.

First a panel of twelve matrons, women who had had experience of pregnancy and childbirth, would examine the woman and bring back a verdict. This was a practice that started in the 13th century, and although rare was more commonly used to decide property cases. A jury of matrons was also appointed when a widow, for instance, claimed that the child she was carrying was an heir or potential heir to a deceased father.

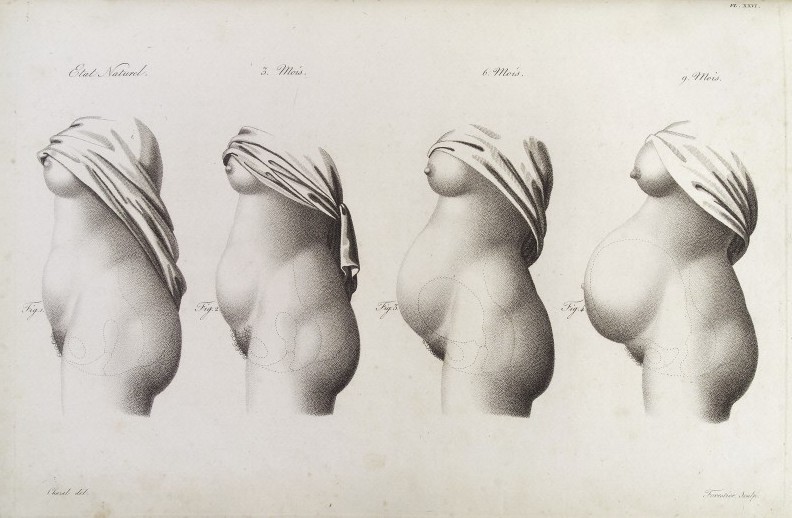

Stages in pregnancy as represented by the growth of the womb from Nouvelles démonstrations d’accouchements. Jacques-Pierre Maygrier (1822) Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

“Barely with child” did not qualify for the exemption. The woman must be “quick with child”, that is the child must have moved in the womb. Essentially, it was the difference between the 15th and 16th week of pregnancy. If the plea was accepted, execution would be deferred until she had given birth.

In practice, women who had pleaded their belly were generally pardoned or transported during this period.

As it turned out, the jury of matrons appointed to assess Ann Hurle failed to come to a conclusion and Dr Andrew Thynne, the first lecturer in midwifery at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, was asked to give his opinion. He declared that she was not pregnant.2

Without the benefit of technology, it was sometimes very difficult to determine whether a woman was pregnant. Generally, all they did was examine the abdomen and palpate the breasts. In the case of poisoner Mary Wright (1832) it was the difference between life and death.

Twelve married women were accordingly sworn to try whether the woman was pregnant with a quick child. The female jury and the prisoner retired into a private chamber; and in the course of an hour returned into court, and gave their verdict that the prisoner, Mary Wright, was not quick with child. Fortunately, the eyes of the profession in Norwich were not closed to the absurd nature of this transaction: three gentlemen, with the humanity which is seldom absent from the minds of superior attainments, procured access to the prisoner next morning, examined her professionally, found her to be pregnant with a quick child, drew up a representation instantly for the judge, to the facts of which they were obliged to swear; and the consequence is that the woman stands reprieved from the execution of her sentence.3

It may have helped that Mr Crosse, who had earlier told the court that Mary’s previous pregnancy, may have made her insane, was amongst the accoucheurs. While incarcerated in Norwich Mary gave birth to a healthy daughter, was respited and sentenced to transportation. She died of unknown causes before that sentence was carried out.

The business of pleading the belly highlights the pitfalls of the law. A woman could be in her 10th week of pregnancy (therefore not “quick with child”) and still be executed.

The turning point came in March 1838 when Anne Wycherley, convicted of drowning her three-year-old daughter, pleaded her belly. The matrons requested the assistance of a surgeon and Mr Greatorex, whose wife was the forematron, was provided to them. He declared Wycherley not pregnant or that if she was she was in the early stage of pregnancy. However, the court respited Wycherley until it was certain she was not expecting and she was hanged at Stafford on 5 May 1838.4

Mistakes over pregnancy verdicts continued, to the horror of doctors and surgeons. In 1843 the British Medical Association passed a resolution condemned the law that allowed a distinction between with child and quick with child, and although the role of the jury of matrons lapsed it was not until 1931 that the Sentence of Death (Expectant Mothers) Act was passed. A woman capitally convicted who was found to be pregnant on medical evidence must be sentenced to life imprisonment.

Ann Hurle, dressed in a morning gown and white cap, went to the gallows in 1804. Her ignominous hanging, from an old-style cart hauled up outside St Sepulchre at the top of Newgate rather than from the New Drop, was objected to by “Humanus” in a letter to The Times.

By the slow and gradual dragging from a cart, their sufferings must be dreadfully protracted, and the unfortunate Anne Hurle is said to have shrieked twice when first she felt the operation of the rope: both the victims appeared in great agonies for a considerable length of time.5

St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, mid 19th century

She died alongside Methuselah Spalding, convicted of “an unnatural crime”.6

- The Times, 18 January 1804.

- Theodric R. Beck and John B. Beck, Elements of Medical Jurisprudence. Thomas Cowperthwait, Philadelphia, 1838, Vol 1, p 176.

- London Medical Gazette, 1832, 12, pp22-26.

- Frederick A. Carrington and John Payne, Reports of Cases Argued and Ruled at Nisi Prius, S. Sweet, London, 1839, Vol VIII, pp262-265; Bell’s Weekly Messenger19 March 1838; Staffordshire Advertiser, 12 May 1838.

- The Times, 13 February 1804.

- Other sources: Bob’s Genealogy Website (The Times transcriptions) and ‘A Jury of Matrons’ by Thomas R. Forbes in Medical History, 1988, 32, pp 23-33.

[…] Sarah was found guilty and, of course, the sentence was death. Her only recourse now was to “plead her belly” – to claim she was pregnant – in order to delay the date of her execution while others […]