In the afternoon of 5 November 1802, John Cole Steele, 35, married and of ‘very amiable character’, left his lavender water shop off the Strand in London, took a stage coach to Hounslow and walked across the heath to Feltham to his visit his lavender nursery. The next day, he set off on the return journey. He did not arrive.

By Wednesday, his brother-in-law was in Feltham making enquiries and, with a gentleman called Mr Hughes, eventually discovered Steele’s body in a ditch. An inquest at The Ship public house in Hounslow was held. It appeared that Steele had been murdered by a blow to the back of the head – his skull was fractured.

A £50 reward was offered and several people were arrested; none was charged. After that nothing happened for four years.

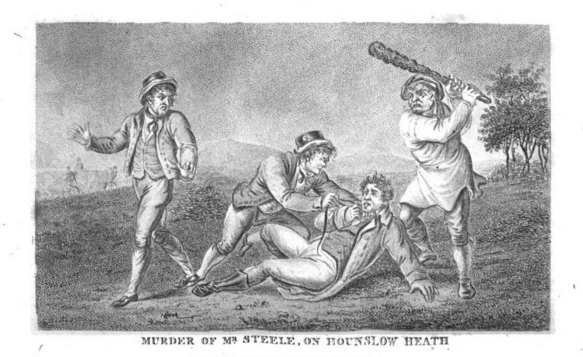

The murder of Mr Steele, from Newgate Calendar, Vol 4. Knapp and Baldwin, London (1810)

In September 1806 at the Old Bailey, 26-year-old Benjamin Hanfield, a former post-boy and army deserter, was convicted of theft and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. He was transferred from Newgate to a prison hulk. While there, he made a disclosure about Steele’s murder to Sir John Carter, the Mayor of Portsmouth, claiming that he had been an accomplice in the attack. He was brought back to London by coach and, without prompting, while passing Hounslow Heath, pointed out the spot where Steele had been killed.

John Holloway, from Newgate Calendar, Vols 3 and 4, Knapp and Baldwin. London (1828)

Hanfield accused two men, John Holloway and Owen Haggerty, both of whom had a record of petty crime, of planning and carrying out the murder and he supplied a vivid account of the incident, full of colourful detail: how Holloway had beaten Steele about the head when he resisted, and how Holloway had stolen and worn Steele’s hat although it was too small and so on. Haggerty and Holloway were duly arrested.

The day before their trial on the 18 February 1807 at the Old Bailey1, the fathers of the accused asked the solicitor James Harmer2 to instruct a barrister to defend their sons. Despite his efforts, they were found guilty and sentenced to hang. At this distance of time they had no alibi.

The day before their trial on the 18 February 1807 at the Old Bailey1, the fathers of the accused asked the solicitor James Harmer2 to instruct a barrister to defend their sons. Despite his efforts, they were found guilty and sentenced to hang. At this distance of time they had no alibi.

Hanfield’s sentence of transportation was commuted and Holloway and Haggerty went to the gallows.

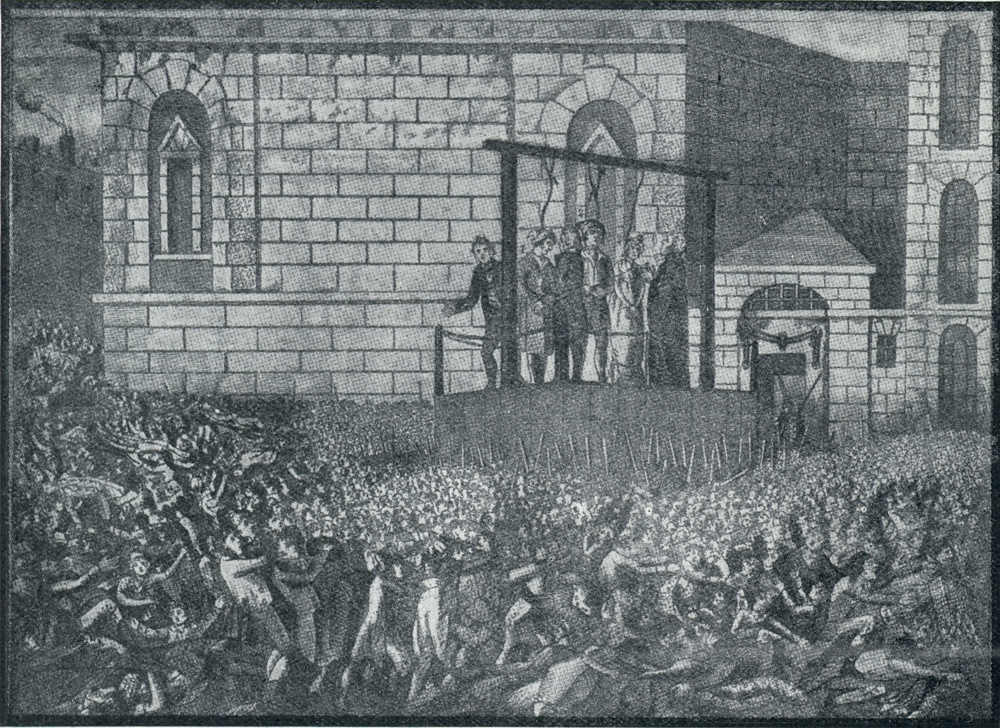

The Old Bailey (1814), from Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts

On the morning of the execution outside the Debtors’ Gate at Newgate, Holloway got down on his knees in the press-yard before the many ‘gentlemen of distinction’ and protested his innocence. Outside in the streets, forty thousand people had come to watch the men die alongside Elizabeth Godfrey, who had been convicted of murdering her partner Richard Prince by stabbing him in the eye. When Holloway ascended the platform he shouted out to the crowd3:

Innocent! Innocent, Gentlemen! No verdict! Innocent, by God!

One version of what happened next was that the axle of a cart in the centre of the crowd broke when spectators climbed on it to get a better view. The crowd surged, with still more people still trying to get on the cart. Another theory is that after a pieman’s stand was knocked down and he tried to retrieve his wares, the crowd became agitated, and the panic increased when people could see others being asphyxiated in the crush.

At this fatal place, a man of the name of Herrington was thrown down, who had in his hand his youngest son, a fine boy about twelve years of age. The youth was soon trampled to death, the father recovered, though much bruised, and was taken to St. Bartholomew’s hospital. A woman who was so impudent as to bring with her a child at her breast was one of the number killed; whilst in the act of falling, she forced the child into the arms of the man nearest to her, requesting him for God’s sake to save its life: the man, finding it required all his exertion to preserve himself threw the infant from him; but it was fortunately caught at a distance by another man, who find it difficult to ensure its safety or his own, got rid of it in a similar way. The child was again caught by a person who contrived to struggle with it to a cart, under which he deposited it until the danger was over, and the mob had dispersed.When the crowd cleared the wounded were taken to Barts. The dead were laid out in the Elizabeth ward to be claimed by their friends.No language can describe the anguish of the scene when the people first recognised these mutilated remains…

Thirty-one people were killed and 40 to 50 were injured. An inquest was held at Barts, under the direction of the coroner Mr. Shelton.

The execution of Haggerty and Holloway and Elizabeth Godfrey. At least 31 people were killed in the crush. (Own collection)

Although he was at first convinced the men were guilty, James Harmer had doubts about Hanfield’s evidence. After the execution, he talked to gaolkeepers and witnesses and published at his own expense a pamphlet in which he asserted that the account Hanfield had given was improbable at the very least. The identification evidence was particularly shaky.4

It was most likely that Hanfield himself had not been involved and was just trying to evade transportation. The clincher was that, some years before, he had made a false confession in which he had admitted to a burglary in order not to be sent back to his regiment to face a charge of desertion (the magistrate saw through him).

In 1813, John Ward was charged with the murder of Steele but was acquitted for lack of evidence on the direction of the judge.5

Date of trial of John Ward amended 9 August 2019 (see Julian Benoit’s comment).

- Old Bailey online

- Harmer was the model for the compassionate lawyer Jaggers in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations.

- From The New Annual Register, Volume 50

- James Harmer, Murder of Mr Steele: Documents and Observations, tending to shew a probability of the innocence of John Holloway and Owen Haggerty

- There is a well-researched account of the murder, trial and aftermath by Linda Stratmann in Middlesex Murders.

John Ward alias Simon Winter went on trial at the Old Bailey on 15 September 1813 not in 1820. He was charged with the murder of John Cole Steele and his accomplice was named as Robert Newton. The Morning Chronicle on Monday, 20 September 1813, stated:

Simon Winter alias John Ward was indicted for the wilful murder of Mr Steele, on Hounslow Heath, in 1802.

Mr Gurney stated the case for the prosecution.

Mr Justice Heath, Mr Justice Dampier, and the Recorders, were all of the opinion, that even if Mr Gurney could prove the facts as stated in his opening, it would not be fit to go to a Jury, and the prisoner was accordingly acquitted without a single witness being called.