After an indifferent and short summer, autumn, my favourite season, has arrived. Usually I am looking forward to all the mists and mellow fruitfulness but this year I am troubled by talk of shortages of food through a lack of workers to bring in the harvest – farming still relies on workers.

My thoughts turned to farming in the 18th and 19th centuries and specifically to the business of bringing in the corn.

The harvest was not only an important festival in the religious calendar but it was an opportunity for a major end-of-season celebrations, a time for the community to come together and work together. Activities need not always meet approval. Charles Vancouver, who surveyed Devon for the General View series in 1808 (an initiative of the Board of Agriculture), complained that the harvest encouraged ‘practices of so disorderly a nature, as to call for the strongest mark of disapprobation, or at least a modification of their pastime after the labours of the day.’2

Unsurprisingly, autumn was seen as a time of romance, an opportunity for intimacy between men and women who worked together closely in the fields.

‘Hence from the busy joy resounding fields…’ Richard Corbould, Autumn, (undated). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Before the ripened field the reapers stand

In fair array; each by the lass he loves

Thomson’s Seasons – ‘Autumn’

After the reaping, the sheaves were brought into the barn, opened and laid out to be threshed with a flail to separate the grain (edible) from the chaff (used for animal feed). This was an exhausting process requiring intense physical strength. The contemporary spelling thrashing gives an idea of the force involved. Vancouver says that in Devon, unlike the reapers, the threshers were paid.

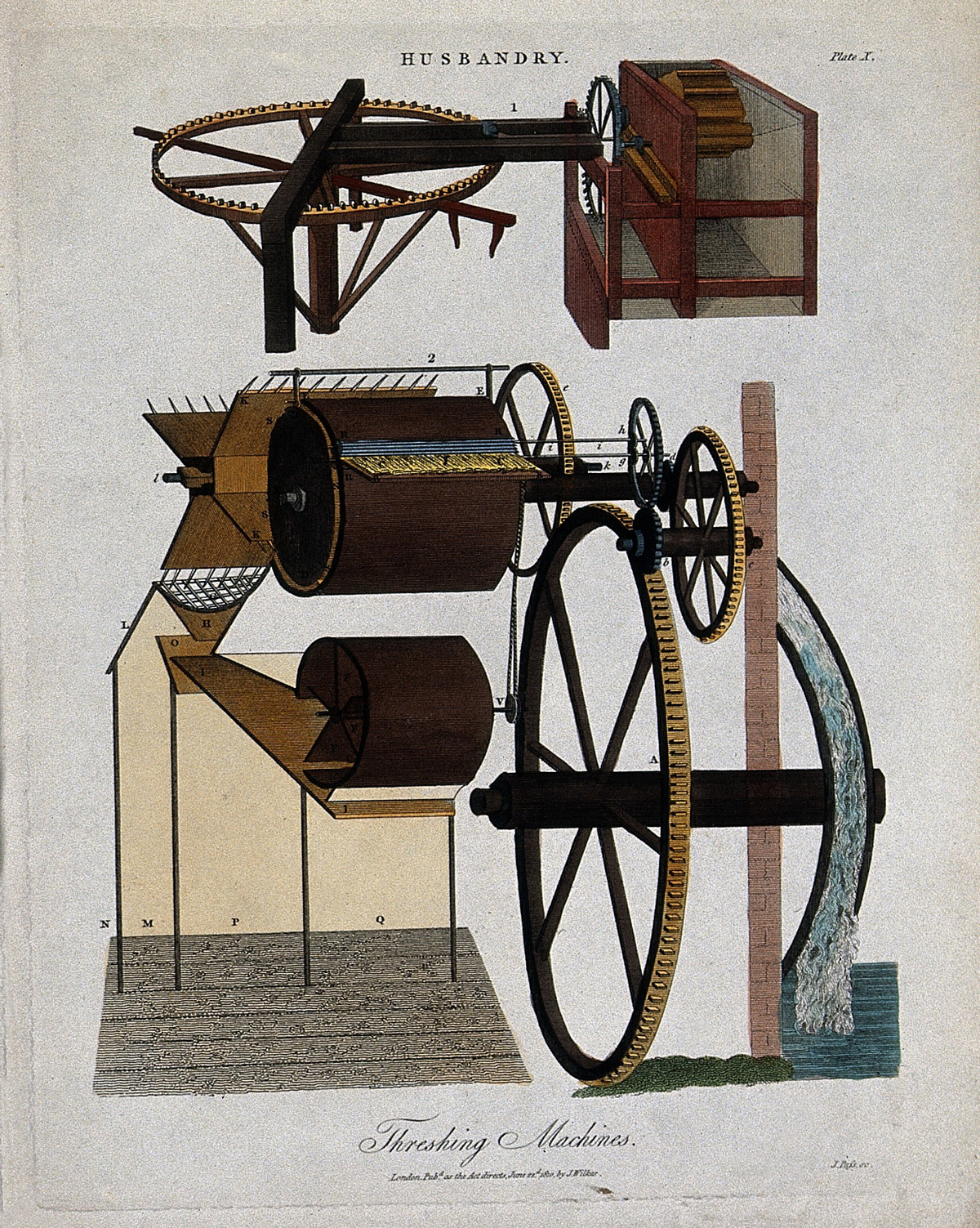

The process of threshing was considerably speeded up with the introduction of mechanisation. Vancouver described what he called a ‘very good’ water-powered threshing machine belonging to Mr Vinn at Payhembury, which could thresh, winnow, grind and could be adapted to crush apples and shell clover seeds. There were horse-powered versions and, later, steam.

Two threshing machines (1810). Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. http://wellcomeimages.org. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Naturally, the machines required less physical strength than manual threshing, which meant that women and children could be employed in greater numbers. Some saw this as an advantage because the men could be directed to more arduous tasks. In Vancouver’s opinion there was actually more employment rather than less and everyone, from the workers to the parish authorities, would benefit.

Unsurprisingly, the workers did not agree with this. They knew that their role overall would be diminished and reacted with anger and threats, and sometimes with riot and machine-breaking. The introduction of threshing machines was a contributory factor in the rural disturbances known as the Swing Riots of the 1830s.

After threshing, the reeds were gathered up and the corn and chaff swept into a pile to be winnowed. Winnowing could be done manually using a ‘fan’.

Le vanneur (The Winnower), Jean-François Millet – The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., Public Domain, Link

Sometimes a machine was used. This was placed in the middle of the barn whose the doors were kept open to create a draught. The grain and chaff were poured into the machine, which ejected the chaff into the farmyard and grain dropped into a bucket at the side, to be packed into sacks and sent to the miller.

Winnowing machine, by Rasbak – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

The last stage was combing the reed. The loose straw and chaff were removed with a large wooden framed comb with iron teeth and the reed dried and used for thatching the roofs of barns and houses and also for protective covers for hayricks.

The ancient celebration of the harvest took place during the Harvest Moon, originally a pagan celebration (the earliest church service for harvest has been traced to 1843 at Morwenstow in Cornwall).

Samuel Palmer (1833). The Harvest Moon. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

- Vancouver, C. (1808). General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon; with Observations on the Means of Its Improvement. Drawn Up for the Consideration of the Board of Agriculture, and Internal Improvement. London: Richard Phillips. Vancouver, a land valuer, wrote several volumes for the General View series.[/ref]

‘Labour’, Engraving by J. Cousen after J. Linnell. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

In Devon, Vancouver wrote, ale and cider is provided to the reapers at eleven o’clock in the morning. There was more drink at dinner time, along with ‘the best meat and vegetables’ (presumably to keep the strength of the reapers up). At five there was a tea of buns and cakes set out under the trees, and the day ended with a game. A small sheaf was set up as a target at which the workers aimed their reap-hooks. The farmer provided supper in a barn, with more ale and cider. The carousing went on until the small hours. The following day, the reapers resumed or moved on to the next farm.

The harvesters would work in rows, with an advance team (of men) scything the wheat, followed by men and women gathering it into sheaves with a sickle or reap-hook. The sheaves were stacked and left to dry.

According to Vancouver reapers in parts of Devon were not paid except in kind: food, drink and the opportunity for a party as well as a standing invitation to the farmer’s house at Christmas for more hospitality. He sniffily described the behaviour of the reapers during this time as ‘assimilated to the frolics of a bear-garden.’

For the same General View series of agricultural surveys, Thomas Batchelor looked at Bedfordshire where the reaping was done by ‘acre-men’, who could earn £6 5s in five weeks.1Thomas Batchelor (1808). General view of the agriculture of the county of Bedford: Drawn up for the consideration of the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement. London: Richard Phillips. Batchelor was a farmer.

Leave a Reply