Madonna once famously, and proudly, said that she had never changed her children’s nappies. Why would she if she could pay someone else? But changing a child’s disposable diapers is not onerous, and even cloth nappies are easily and hygienically scraped, soaked and washed. Or sent to a laundry service.

It was not always this way. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the business of keeping a baby clean involved endless labour: touching filth and washing ‘clouts’ by hand without the benefit of rubber gloves.1

Soiled clouts would have to be scraped and soaked. They might be boiled and rubbed with lye soap, and finally rinsed, before going through the mangle and hung up on bushes, racks or lines to dry. The responsibility for this fell entirely to female servants, and usually specifically to the nursemaid.

Lady’s Maid Soaping Linen, 1769. After Henry Robert Morland, 1730–1797. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

It was drudgery. All washing was back-breaking work, involving lifting and carrying large pails of water, lighting fires for the copper boiler, and scrubbing with harsh substances: lye soap, chalk, brick dust, pipe clay, alcohol and urine (a natural disinfectant). And the more numerous the family the more work for the nursemaid.

There was also the child itself to keep clean.2

The child’s skin is to be kept perfectly clean by washing its limbs morning and evening, and likewise its neck and ears … Clean cloths, every morning and evening, will tend greatly to a child’s health and comfort.

Mother and Infant, ca. 1798, James Ward. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Nursemaids, and servants in general, engaged in caring for the children of the house, were caught in a bind. As social inferiors to their charges, they were not allowed to physically chastise them – that was the province of the master or mistress – but they had to at all times offer appropriate guidance, maintain control and ensure safety. In some households, the servants could be disciplined by the children. For some the injury to their self-esteem must have been devastating.

In 1799, the Proctor family, living in Royston, Hertfordshire, engaged Ann Mead as a nursemaid for their children, including Charles, then only a few months old. She was not a parish cast-off, but from an established family, the youngest of five children of Simeon and Martha Mead. She was 14 but her youth was not unusual. I have already described the life of Mary Ann Whitby, who joined the Tuckett’s seven children when she was 13.

The Proctors may not have considered Ann’s personality carefully enough, or understood the power of hormones to severely reduce empathy in teenagers. Anyone who has shepherded adolescents through this difficult period knows that while their egos are easily bruised and they often have an intense and heightened sensitivity to insult, they can also be astonishingly callous towards others, seemingly impervious to reason and monumentally selfish.3 Mrs. Proctor threw out a rebuke (perhaps one of many) in a moment of anger and could not have predicted Ann’s reaction.

Yesterday se’nnight was committed to Hertford Gaol, Ann Mead, aged 15, for poisoning the infant child [he was 18 months] of her master Mr. Proctor, of Royston. A powder was found in its stomach, which, from experiments that were made, was declared to arsenic. After many declarations of her innocence, on cross examining her closely, it came out the child had swallowed a powder; and she afterwards confessed that she had given it a spoonful of arsenic, and assigned as a reason for the act, “that her mistress called her a slut, and she was resolved to spite her”. 4

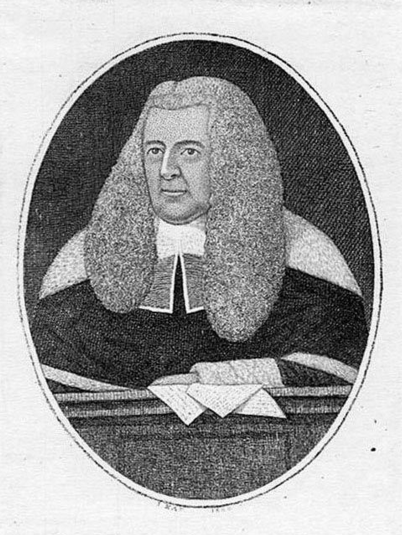

Justice Nash Grose

Newspapers reported scant details of Ann’s trial at the Hertford assizes in front of Justice Nash Grose (1740–1814), although there was a slight expansion on the reason for her fury with Mrs. Proctor.

It seemed she had been induced to commit this horrid act, merely in malice to her mistress, who had found fault with her for not keeping the child so clean as she ought to have done.5

Perhaps the endless rounds of washing clouts, cleaning the children and obeying her mistress, became too much for Ann to bear. She probably did not think through the natural consequence of that spoonful of arsenic: discovery, grief, accusation and arrest. All she had in mind was revenge on Mrs. Proctor and the ending of a miserable employment.

Ann went to the gallows at Hertford on 31 July 1800, aged 16.

- The clout was fastened with straight pins or tied with lacings and covered by a ‘pilcher’, an outer protective layer.

- The Complete Servant; Being a Practical Guide to the Peculiar Duties and Business of all Descriptions of Servants, From the Housekeeper to the Servant of All Work, and from the Land Steward to the Foot-Boy, by Samuel and Sarah Adams. London: Knight and Lacey, 1825

- Some teenagers are angels, obviously. But not many. Luckily, for most, it is a phase.

- Northampton Mercury, 28 June 1800.

- Sussex Advertiser, 4 August 1800.

That was a lot of work for a girl. Circumstances had me washing cloth diapers in a tub once. I Don’t forget that the other clothes and bed linen of the child had to be washed as well. Back breaking work. One regency expert complained that nursemaids were letting the infants sleep in urine soaked clouts and gowns to save the juices — much as one would baste a turkey. The substances used to clean the baby’s clothes and cloths could also irritate an infant. There must have been many a sore, red bottoms in nurseries around the country. Poor babies. In this story, definitely poor baby. Still, the idea of hanging children is repugnant.

I do like your blog.