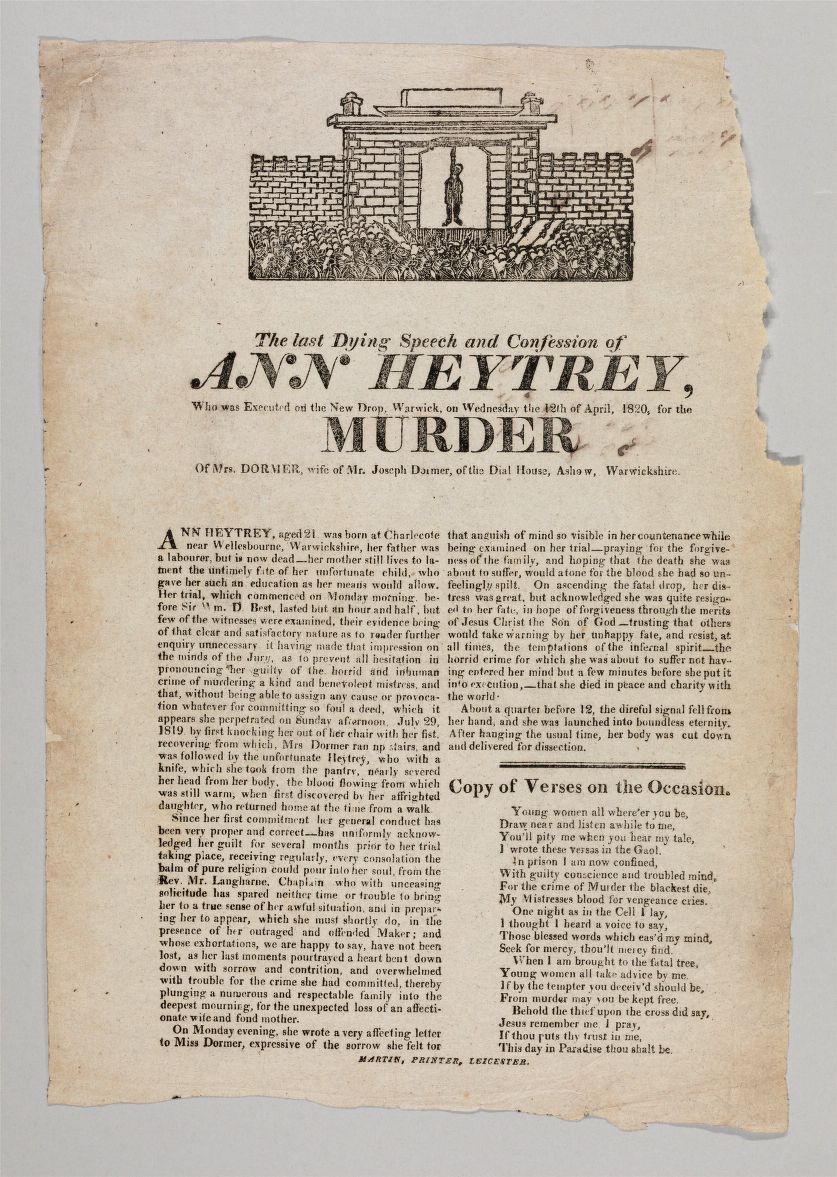

In prison I am now confined,

With guilty conscience and troubled mind,

For the crime of Murder the blackest die,

My Mistress’s blood for vengeance cries.

[from a broadsheet published on the execution of Ann Heytrey, 1820]

Sunday 29 August 1819 was a glorious day in the Warwickshire village of Ashow. Hot and fine, it was perfect for the enjoyment of the day’s celebrations, the annual thanksgiving festival known in that part of the world as a wake. Everyone from from the village and round about was there, including Joseph Dormer, a prosperous local farmer who lived at Dial House Farm, his six children and three of his four servants. Dormer had also invited two of his business associates along and they had all enjoyed the jollity – travelling musicians, trinkets for sale and village games – until it was time to return home for lunch with Joseph’s wife Sarah.

Sarah had stayed behind to prepare the meal, helped by her servant, 19-year-old Ann Heytrey, who was something of a “project” for the Dormer family. Ann’s father, an agricultural labourer, had died a few years previously, leaving his wife and children in dire poverty. The family had problems. Ann’s brother Thomas, a blacksmith, was consorting with known thieves and Ann herself had been caught trying to steal banknotes from the house. The Dormers, who thought Thomas was behind the incident, were fond of Ann, and Mrs Dormer had urged her husband to drop the charges and insisted that she continue to work for them. Ann had been saved from certain transportation, or worse.

After lunch at Dial House,1 Joseph Dormer’s guests, who had been joined by two others, stayed for tea and an afternoon of conversation, and at about six, the party, children included, decided to take advantage of the fine weather to take a walk. Some of the children went to the village of Thickthorn, not far away, to see a friend, and Mr Dormer and his guests went back in to Ashow.

At about half past six Mrs Dormer’s young niece and nephew came to the back door of Dial House, where Mrs Dormer gave them a drink of wine2 and some cucumbers. Shortly afterwards, Elizabeth Jaggard3 passed the front of Dial House and saw Sarah Dormer in the window, spectacles on, with a book in her hand. She also saw Ann Heytrey come out of the house, look towards Ashow and rush back in again.

At around ten past seven, four of the children, John (18)4, the oldest, Elizabeth (17), Mary (14)5 and Harriett (13)6 arrived back at Dial House first. Opening the back door, they saw Ann in the passage. She was agitated and confused, sweating heavily. Elizabeth, seeing that something was wrong, asked if anyone had been in the house.

“No, nobody,” said Ann, and went out to the wood yard. The children were disconcerted. They had expected their mother to be nearby, to call to them from the kitchen or to come out and greet them.

Elizabeth saw smears of what she thought was elder wine on the floor.7

It looked as if someone had tried half-heartedly to wipe them up.

“What have you been doing?” Elizabeth asked Ann, who had soon come back in the house.

“Oh, nothing.”

Elizabeth told her to bring a mop and clean the floor, which she did.

“Where is my mother?” asked Elizabeth. Ann told her that she had gone towards Ashow, so John went out to look to look down the road for their mother, but when Harriett, who had been calling out to her mother, asked Ann the same question she said that her mistress was picking cucumbers in the garden.

Mystified, Elizabeth went upstairs to her room, followed by Mary, who pushed open the door of her mother’s chamber. When she saw her mother on the floor, she started screaming.

“Oh, my mother is murdered! My mother is murdered!”

John immediately ran upstairs and found his mother on the floor in a pool of blood, her throat slashed and her face smashed. A knife was nearby.

Mary’s cries were heard by Mr Bodington, a surgeon, who happened to be passing on his horse.8

They were so piercing that he immediately rode right up to the door and came in the house to assist. Of course, there was nothing he could do for Mrs Dormer. He could see that someone had cut her throat so violently that her spine had been severed, and that there were two deep cuts on her jaw. Her middle finger on the right hand had been cut in two or three places and there was extensive bruising. He sealed up the room and sent for the Kenilworth constable, Thomas Bellerby.

There was only one suspect, Ann, who was distant, diffident and uncommunicative (“sullen” according to those who dealt with her). In the immediate aftermath of the discovery of his mother’s body, John Dormer had dragged her outside and slapped her in the face. She merely responded:

“You have no occasion to pull me, I’ll go where you have a mind to take me.”

Now, when Bellerby asked her whether she was the servant who had killed her mistress, she merely said:

“They say so, but I am not.”

Mr Bodington and Mr Hiron performed an autopsy and an inquest was held two days later, at which Ann stated that she was innocent of the crime and that she had not left the house except to go out to the woodpile. But it was obvious she had been involved – there was blood on her hands and under her nails. At first Bellerby was convinced that Ann’s brother Thomas must have been involved, but Ann fiercely denied it.

What a thing it is to bring my friends into trouble. Neither my brother nor no other man had to do with the murder.

She went on to confess and give an account of events, telling Bellerby:

That she was left alone with her mistress, and while employed in preparing some cucumbers for supper, which she and the deceased had just cut, a thought struck her that she would murder her.9

The attack was sudden, swift and brutal. Ann had gone into the kitchen, where Sarah Dormer was reading, and “with her fist knocked her from the chair”. In shock, Mrs Dormer had run upstairs, at which Ann had gone to the pantry, taken a knife and pursued her. Mrs Dormer had tripped and fallen on the floor, where Ann had attacked her with the knife. Mrs Dormer did not cry out. She had left the knife there to make it look as if she had “destroyed herself,” and returned to the kitchen. Ten minutes later, the children arrived at the house.

The inquest jury brought in a verdict of wilful murder against Ann and she was conveyed to Warwick Gaol to await the next assizes.

Now that she had admitted her guilt, it was the duty of the prison chaplain to ensure that she was properly prepared for her future, which would no doubt be short, and to this end the Rev. Mr. [Hugh] Laugharne attended her every day. “With unceasing solicitude [Laugharne] has spared neither time or trouble to bring her to a true sense of her awful situation.”10

In April Ann Heytrey appeared before Mr Justice Best charged with petty treason and murder. This archaic crime, which was downgraded to murder eight years later, was a common law offence involving the betrayal of a superior by a subordinate. High treason related to the monarch, while petty treason related to persons below that – that is, an ecclesiastical superior, an employer or a husband (for, of course, all women were subordinate to their husbands).

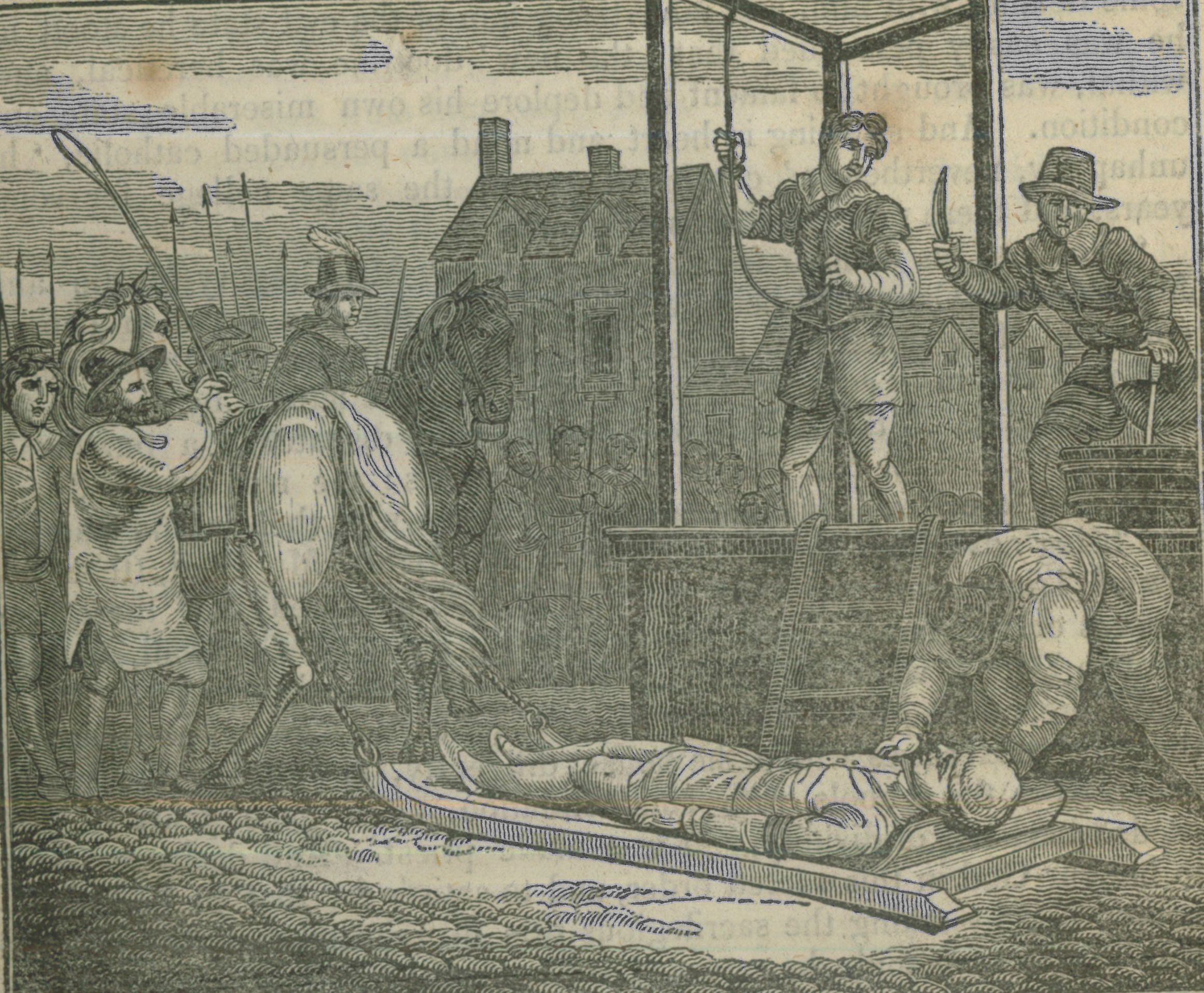

The punishment for petty treason carried an extra layer of punishment. Not only would the guilty be hanged and afterwards dissected, but on the day of their death they would be dragged through the streets tied to a hurdle (a wooden panel or pallet) behind a horse. This practice was designed as a symbol of disgrace: the condemned were prone, near the floor and facing backwards.11

In court Ann wore a black gown and grey shawl, with a muslin mob cap. She was impassive while the witnesses, including Elizabeth and Mary Dormer, gave their evidence. As she was unrepresented, she was asked each time if she had any questions for them. She did not, nor did she have any witnesses of her own to call. After the testimony, the jury consulted for a few minutes and brought in their verdict: Guilty of both petty treason and murder. Did she have anything to say? asked the court. She replied firmly, “No, I have not.”

From prison, Ann wrote a letter to the bereaved daughters of her mistress.

…I am heartily sorry for the sorrowful misfortune as has happened which I hope the Lord in his mercies will forgive me and I was very sorry to see you look so bad [Ann saw in court that Elizabeth had been deeply affected by the trauma of her mother’s death].

On the morning of Wednesday 12 April Ann took communion with the Rev. Mr. Laugharne. A short time later, he accompanied her to the New Drop in front of Warwick gaol, where a large crowd had gathered. Her “distress was great”.12

but she remained stoic. As the Staffordshire Advertiser13 put it:

The firmness, bordering upon hardihood, though strictly decorous, which distinguished her during her trial, remained to the last moment.

When the cap was put over her face, she was asked again, for the last time, about her motive for killing her mistress.

I cannot tell. I had none, but that I thought I must murder my mistress.

The “direful signal” was given at a quarter to twelve and she was “launched into boundless eternity.” There was nothing in the newspaper reports about her ordeal on the hurdle.

Earlier, she had been questioned about her feelings about Mrs Dormer14

“Had your mistress done or said any thing in the course of the day to offend you?

“She had not given me an angry word.”

Now, perhaps for the first time, Ann showed real emotion. She burst into tears and said, “I liked my mistress so much, I would have got up at any hour of the night to serve her.” It was, she added, a sudden explicable impulse, with no idea of robbery in it.

After Ann was cut down, her body was given to Mr. Bodington, the surgeon who had first seen Mrs Dormer’s body and afterwards conducted the autopsy. Her grave is unknown.

Sarah Dormer was buried in Ashow churchyard, where 11 years later she was joined by her husband.

What on earth had happened that idyllic evening? And why had Ann apparently turned on her mistress, who had done so much for her? What could account for Ann’s bizarre behaviour? She appeared to be more-or-less normal afterwards, although somewhat dazed and silent, but had an almost complete inability to explain what had driven her to murder.

Psychology as a science did not exist, and Ann would not have been interviewed by a doctor to eliminate mental illness as a cause of her actions. On rare occasions, murderers who were clearly “insane” were sent by the court to the madhouse rather than to gaol, but Ann was not raving, talking of voices in her head or seeing things that were not there.

It goes without saying that our understanding of mental breakdown has highly sophisticated compared to 200 years ago. At that time, Ann Heytrey’s motivations were mystifying, possibly because her crime was so rare. Resentment against an employer might manifest itself as rudeness, disobedience or insubordination, or even theft of objects and money (as indeed Ann had already attempted), or cruelty towards the children in the house.

One of the few available explanations was physiognomy, the pseudo-science that explained moral failings by an assessment of the physical appearance of the transgressor. At trials, defendants were on display, subject to the scrutiny of the public and of journalists. What they found was that Ann was generally unremarkable in appearance. She was judged to be a “middle-sized woman, and stoutly made; had high cheek-bones.” However, Ann was also the possessor of “a physiognomy well calculated to conceal a criminal heart.”15

In other words, you couldn’t tell that she was a criminal from the cast of her face, because she had a face that was designed to conceal her nature.

Even if the court had recognised that Ann was mentally ill at the time she killed Sarah Dormer, she would still have had to convince the court that she could not distinguish between good and evil nor was capable of understanding the consequences of her actions. This was plainly not the case.

There are two sad postscripts to this story. Less than a year after Ann’s execution her mother Mary16 “died of a broken heart”.17

. Not only had she endured the shame and ignominy of her daughter’s crime, trial and condemnation, but now her youngest son, Thomas. was in prison awaiting his own trial for murder.

At the Warwick Assizes in April, a year almost to the day after Ann Heytrey met her end, 37 prisoners were condemned to death. Amongst them were four men – Nathaniel Quiney, Henry Adams, Samuel Sidney and Heytrey – who on 7 November at Littleham Bridge had murdered William Hiron on his way back from voting in the county election. Hoping to rob someone else entirely, they had lay in wait and pulled him off his horse using a large hook attached to a pole, which they had made especially for the purpose. They then brutally bludgeoned him, leaving him for dead. In fact, after they had fled, Hiron, his skull smashed, managed to crawl away but ended up in a ditch, where he was found the next morning. His injuries were so severe that he died two days later.

The booty amounted to three pounds notes, some coins and a pocketbook. The gang were soon caught and, tricked into making confessions. The jury had no trouble finding them all guilty, and, with the others, Thomas Heytrey followed his sister to the gallows on Saturday 14 April.

- Lunch was probably served in late afternoon

- Much watered down, as was the custom.

- Probably Elizabeth Umbers née Jaggard of Leek Wootton, Warwickshire (1793–1850)

- Probably 1801–1849

- Probably b. 1806

- Probably 1805–1856

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 11 September 1819. Report on the inquest.

- I am indebted for much of the detail of the events after Sarah Dormer’s body was discovered to Nick Billington’s Foul Deeds & Suspicious Deaths in Stratford and South Warwickshire, Wharncliffe Books (2013) and Vanessa Morgan’s Warwick Murder and Crime, The History Press (2013)

- Staffordshire Advertiser, ibid.

- The Last Dying Speech and Confession of Ann Heytrey, Who was Executed on the New Drop, Warwick, on Wednesday the 12th of April, 1820. Martin, Leicester (1820).

- Until 1793 women guilty of petty treason were burnt at the stake, although many of them were dead before they reached the flames, either finished off by the executioner or occasionally, by their family and friends. Those guilty of high treason were hanged, drawn and quartered.

- The Last Dying Speech. Ibid.

- 22 April 1820.

- Probably by the Rev. Mr. Laugharne, who had daily access to Heytrey. An unattributed account was included in the Staffordshire Advertiser’s report on 22 April 1820.

- The Annual Register, 1820. Baldwin (1822).

- Née Rawbone.

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 3 March 1821.

I bought the book Murders in the Midlands a few years ago and seem to have lost it. Where can I buy it again?

Ann and Thomas Haytree (heytrey) were my ancestors.

– Best place to try is Amazon or Abebooks, I would say. I also cover the murder of Mrs Dormer in my book Women and the Gallows.

Thanks. I will try them.

Hi Naomi

You seem to have got John and Joseph mixed up, John was the youngest, and Joseph was the eldest son, no mention of James Harris Dormer ?

Regards

David John Eason

avengingangel1820@yahoo.com

Naomi

You say that Ann had, punched Sarah in the face, in the best kitchen, so why was it when Thomas Bellerby arrived at 20.30pm and examined Ann’s hands he found no bruising, cuts or grazing ?

You say that Ann was discovered still in the house, which Ann had confirmed herself having never left the house after Sarah’s murder, which questions, if true, where did the blood stained towel and apron found in the tub of soapy water in the back garden, and another blood stained apron found rolled up on the shed floor adjacent to the back door come from, and who put them there if she hadn’t left the house ?