Ah Christmas. These days magic has clean gone out of it. It’s all about showing off, too many presents, getting drunk and bad sex at the office party. Hmmm. Actually, if you look at this selection of 12 depictions from the late 18th century to the early 19th, you might think nothing much has changed.

Note: I feel it’s such a shame we have lost the word ‘gambol’ which means to romp or cavort. Seems to have been a lot of it going on at Christmas.

Day 1

Francis Wheatley, 1747–1801, British, The Mistletoe Bough (c. 1790). Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

In this rustic scene London-born Francis Wheatley (1747-1801) titillates by showing behaviour on the wrong side of proper. Under the mistletoe a young man has a young woman around the waist, his hand dangerously close to her breast. To their right another young woman has collapsed to the floor. Has she had too much to drink? To their left a pregnant woman and her partner show, perhaps, what too much fun can lead to. Meanwhile, a basket of laundry is upset. The household is clearly going to rack and ruin. In the background the older generation look on. When a wild and dissipated young man Wheatley ran off to Ireland with a married woman but by the time he painted this scene he was in his forties and had settled down with his wife, Clara Maria Leigh, another artist.

Day 2

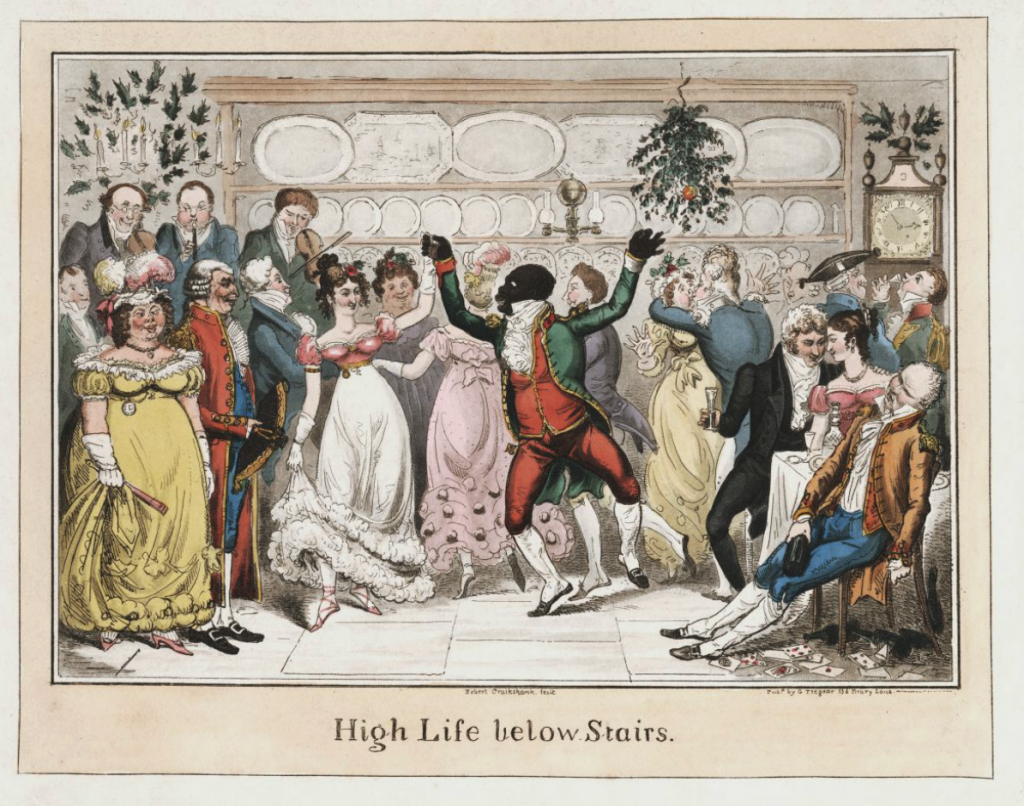

Robert Cruikshank, High Life Below Stairs (1825?). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library.

Mistletoe features in this party in the basement of a grand house where a black footman (here in full minstrel-type caricature) dances with the ladies. It looks like the toffs have come downstairs to muscle in on the action – a particularly smooth specimen is canoodling with a woman on the right while a drunken footman, oblivious, falls off his chair.

Day 3

John Massey Wright, The Ghost – a Christmas Frolic (le revenant) (1814). Courtesy of Library of Congress

A small boy interrupts the Christmas fun fools his family and their guests into believing that a ghost has risen from the grave. Again, a branch of mistletoe hangs from the ceiling but now it’s completely ignored. Centre stage is another black man who looks at the ‘ghost’ challengingly.

Day 4

Henry William Bunbury, The Christmas academicks, playing a rubber at whist. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

There’s no mistletoe in this etching showing scholars letting their hair down at Christmas. They’ve hung up their mortarboards and gowns and settled down to a friendly game of cards. An old crone helpfully offers a soothing libation, but but only one glass (perhaps they are sharing). Caricaturist Henry William Bunbury (1750–1811), the son of a baronet, was as famous as Rowlandson and Gillray but, unlike them, never produced political satire and so his reputation faded.

Day 5

Thomas Rowlandson, Christmas Gambols (1812). Courtesy of Princeton University Digital Library

Christmas has got utterly out of control in this household. In the servants hall, everyone is under the influence of drink and mistletoe and is indulging in ill-advised sexual horseplay. There will be sore heads in the morning. Interestingly, it’s another Christmas scene featuring a black man, proof perhaps that life in Britain was more diverse than we have properly appreciated.

Day 6

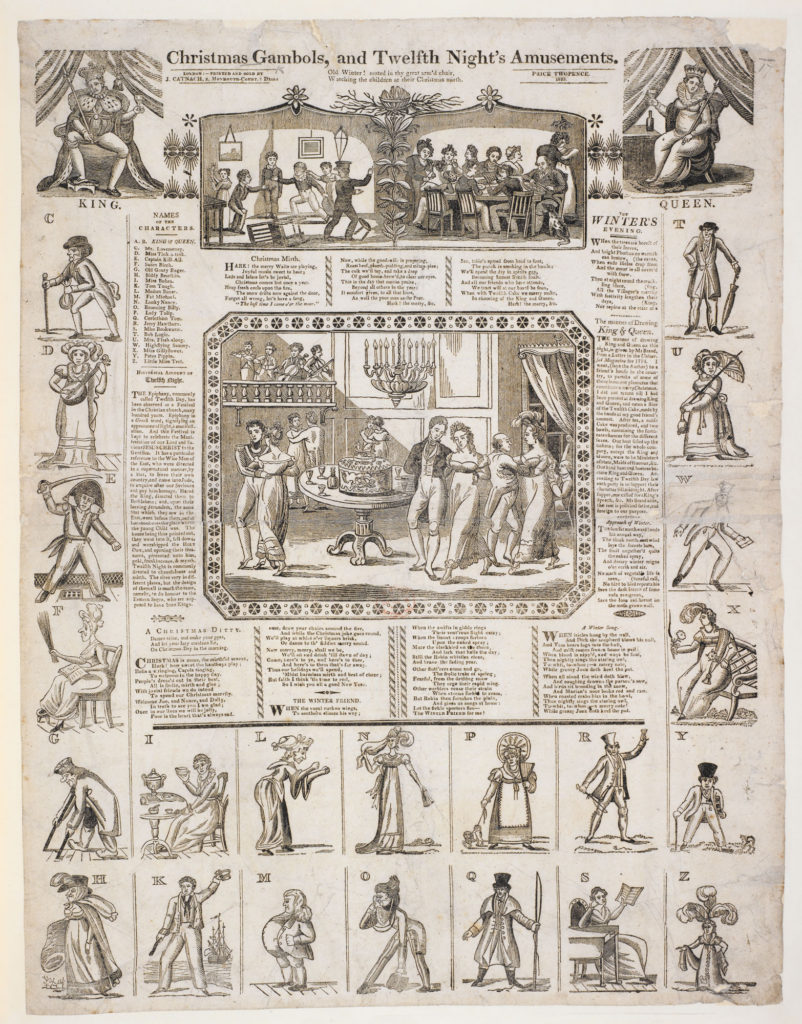

Broadside published by James Catnach, Christmas Gambols, and Twelfth Night Amusements (1823). Courtesy of the British Library Collection

This broadside sold for tuppence (2d), double or even quadruple the price of most sheets (and from this we can assume it was aimed at the middle-class market). It gives a mix of seasonal song lyrics and depictions of characters and games (such as blind man’s buff). Amazingly James Catnach, one of the most successful and prolific mass-market broadside publishers, produced his sheets on his father’s old wooden presses in the family home in Seven Dials, London.

Day 7

Samuel Collings, Christmas in the country (1791). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library

A jolly country Christmas party but with not too much ribaldry. A couple in the back surreptitiously take advantage of the mistletoe while the others imbibe freely of the wassail bowl. A practical joker pours punch into a man’s pocket while the women tease the men about what lies under their wigs. It’s all pretty good-natured. Not much is known about Collings, who was a friend of Thomas Rowlandson.

Day 8

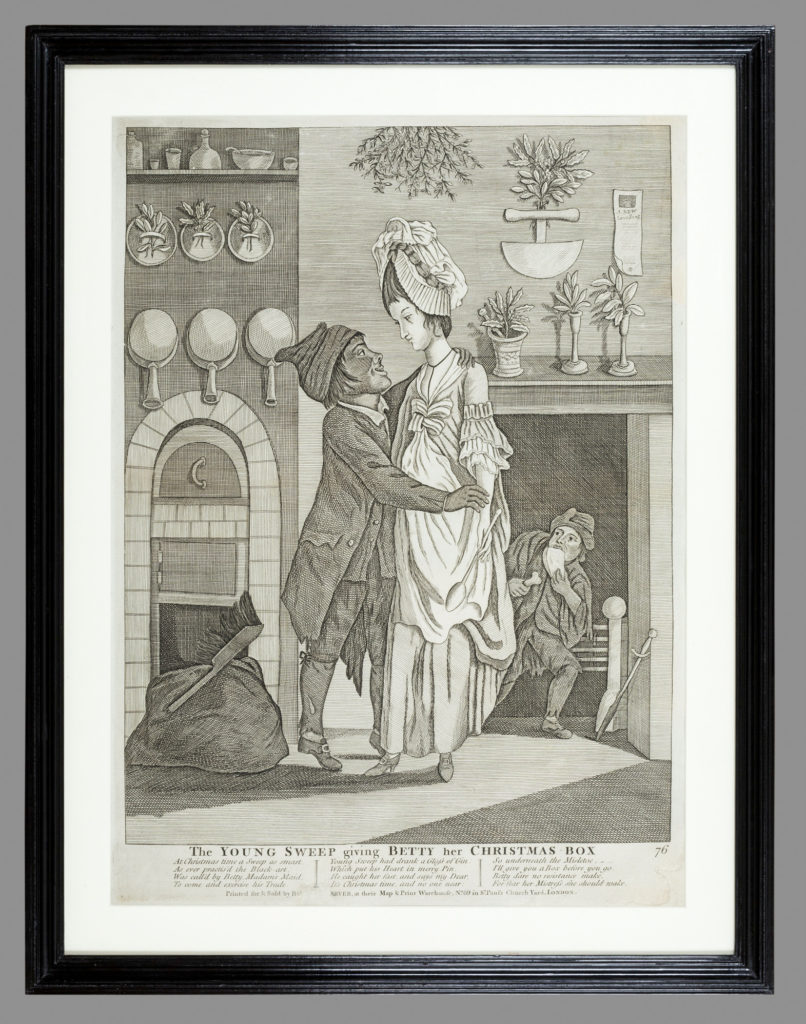

Anonymous, The Young Sweep Giving Betty Her Christmas Box (1770-1780). Courtesy of Winterthur Museum Collections

Very depressing, this one. Housemaid Betty looks none too happy at the prospect of a ‘Christmas box’ from the sweep who, according to the rhyme printed below the image, has just had a glass of gin and has now ‘caught her fast’ under the mistletoe. Betty, apparently, is concerned that her mistress will be woken and therefore decides to make ‘no resistance’. I expect she would join in with the #MeToo campaign. The small, deformed climbing boy behind her devours some paltry Christmas fare.

Day 9

Edward Penny, Christmas Gambols (1796). Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library

Back to gambolling. Another genre scene of Christmas gambols and mistletoe, this time with a quote from Milton: ‘Whilst Romp loving Miss is haul’d about/ With gallantry robust’. Interestingly, the couple in the background seem to be minus feet. Edward Penny (1714–1791), a founder member of the Royal Academy of Arts, who was originally from Knutsford, Cheshire but moved on to London, was primarily known as a portrait and historical painter.

Day 10

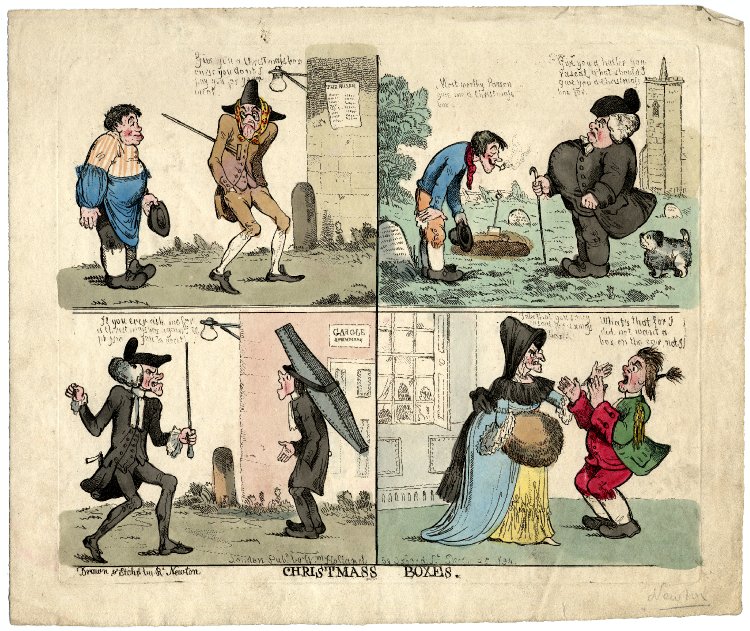

Christmas boxes (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

Several grumpy bananas here. In this satirical print, four scenes show people trying to collect their Christmas boxes, only to be met with ill-temper and resistance. Unfortunately, I am unable to decipher the speech bubbles.

Day 11

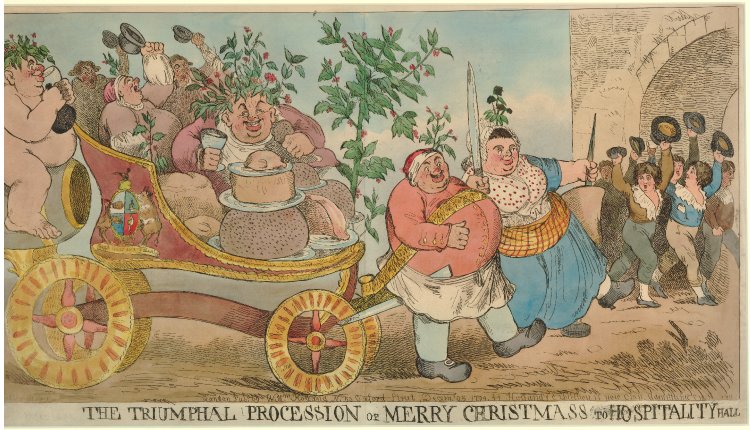

Richard Newton, The triumphal procession of Merry Christmas to Hospitality Hall (1794). Courtesy of the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

Richard Newton (1777–1798) created this satirical print when he was only 17. His prodigious talent, alas, was snuffed out when he died of typhus at the tender age of 21. Newton’s depiction of the gluttony and excessive drinking during Christmas, in which gross men eating huge pieces of meat are pulled on a carriage by two fat people and followed by a naked man seated on a barrel, is original and rather bonkers. The scene is festooned with holly, which makes a change from mistletoe.

Day 12

John Burnett, Christmas Eve (1815). Courtesy of the Wellcome Library

Finally… A rural Christmas Eve genre scene, in which a woman plays cards with her weary mother or mother-in-law while her husband leans lovingly over her shoulder and her grinning child watches. A branch of hanging mistletoe ensures that the happy married couple are in the mood for later. John Burnett (c 1781–1860) was a Scottish-born engraver and painter.

And with that, I wish you all a fantastic Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Day 10: the man in the picture at the lower right objects to being given a box on the ear.

Day 11: the naked man on the barrel is Bacchus, god of Bacchanalian revels.