Two, yes, two Gainsborough exhibitions in the space of a week. Who knew that I liked Gainsborough that much? I, for one, didn’t… But I do now. After seeing his early work at a special exhibition at Gainsborough’s House museum in Sudbury and his portraits of his family at the National Portrait Gallery, I am a convert. His light touch, his rapid, fluid brushstrokes, his sense of humour, his ability to animate his subjects, all are a revelation to me. Famously, he preferred to paint his beloved Suffolk countryside to the endless boring Suffolk worthies commissioning portraits, but for me his family subjects, which included the family dogs, surpass all.

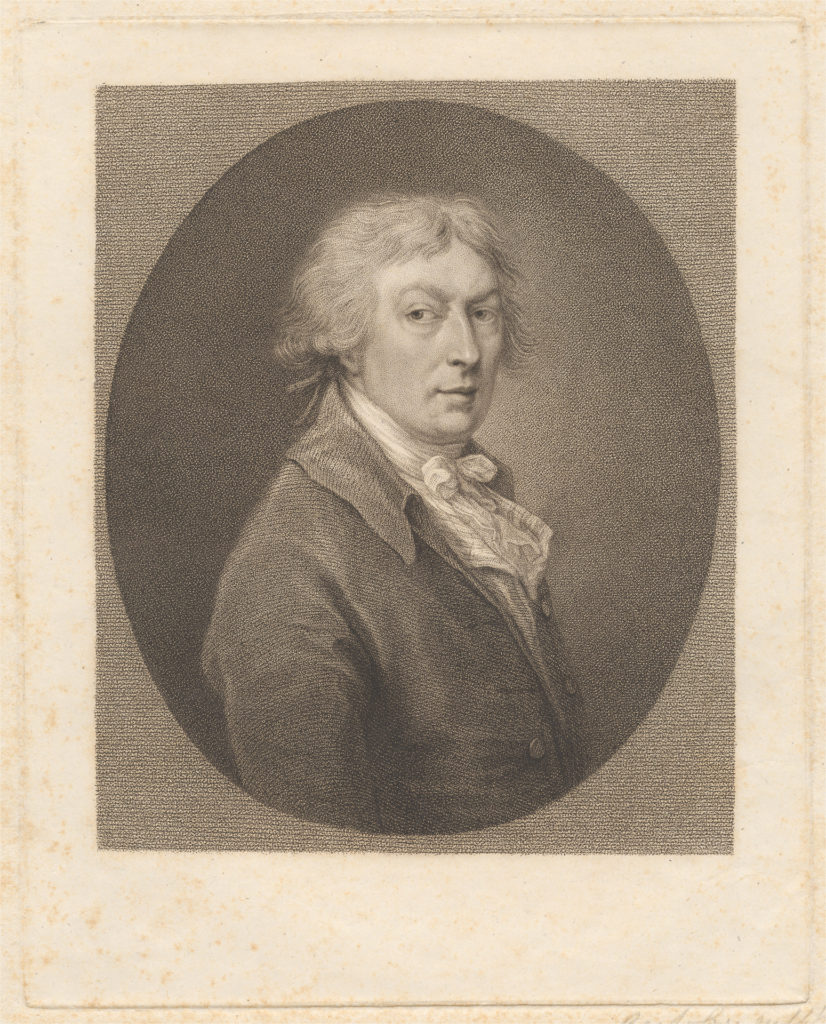

Thomas Gainsborough, a print after a self-portrait by Thomas Gainsborough. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Thomas Gainsborough, born in Sudbury in 1727, was one of nine children of John Gainsborough and Mary Borrough. He was educated at the local grammar school, which was run by Mary’s brother, the Reverend Humphry Burroughs, but was not a particularly good student, preferring to roam the countryside, sketchbook in hand. Although it was seemingly an ideal childhood, perhaps he was also keen to escape home. John Gainsborough went bankrupt in 1733, when Thomas was six, but was helped out financially by his brother, Thomas. To make things a bit clearer I’ll call this Thomas, the artist’s uncle, Thomas senior; senior had a son, Thomas junior, the artist’s cousin.

A few years after John’s bankruptcy Thomas senior became embroiled in events that were to lead to his son’s murder and his own. And, ironically, it was these murders that allowed Thomas Gainsborough to build his career as an artist.

Thomas Gainsborough was born at the house in Sudbury Suffolk that was acquired in 1958 by Gainsborough’s House Society and turned into Gainsborough’s House museum.

In 1732 one of Thomas senior’s creditors, John Barnard, a mercer of Sudbury, went bankrupt. This meant that Thomas senior was allowed to claim the debts due to Barnard. Among those he pursued was Richard Brock, but all attempts to recover monies from Brock were unsuccessful. After Thomas senior started to prosecute Brock, his attorney, Richard Sabine, received an anonymous letter including the words:

I understand that you have ruined my friend Brock to all intents and purposes, which you must expect to suffer, for ruining a family so basely as you have done; that is, I mean in the next world you must expect to suffer for, in this I know your wealth will protect you.1

Later, another letter was received, specifically targeting Thomas junior:

Mr. Gainsborough, fail not of acquitting Brock directly of his trouble; if you don’t by G— revenged of him your son we certainly will be. I am your friend, to acquaint you of the real design, for as sure as ever he was born, he will be put to an ominous end…

There was a deadline of 10 September and five days later Thomas junior was dead and buried. This did not deter Thomas senior, to whom the next threatening letter was addressed.

By god you shall never come to London safe; for, damn you, you will have no more mercy than the devil will have of you; and your rogue of a lawyer shall certainly drink out of the same cup.

Six months later, in March 1739, Thomas senior was murdered at the Golden Fleece in Cornhill, London. No one was charged or convicted for either of the murders.

Mr and Mrs Carter by Thomas Gainsborough (1747-8). John Gainsborough died in debt to Mr Carter. Was the unflattering appearance of his subjects Thomas’s subtle punishment? Photo credit: Tate.

Like his siblings, Thomas Gainsborough, who was then aged 12, was left £10 in Thomas senior’s will, but a note singled him out, asking the executors to ‘take care of Thomas Gainsborough… that he may be brought up to some light handicraft trade likely to get a comfortable maintenance.’ He was granted an additional £10, which paid for him to go to London to work with engraver Hubert-François Gravelot and then with painter Francis Hayman. The bequest set him up for life. (You can read more about the murders and how Mark Bills, director of Gainsborough’s House, researched them at The Art Newspaper.)

Thomas Gainsborough, Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape (c. 1750). Credit: Tate.

The Sudbury exhibition is small – displayed in two rooms in the museum, which is Gainsborough’s birthplace – and focuses on the artist’s early life and art. It takes Gainsborough’s story up to to 1748, when he returned to Suffolk from London, and includes paintings, drawings and ephemera from the collection, new acquisitions and loans. Gainsborough’s paintings during this era show his great love of landscape – to my eye, at this stage he had more skill here than in the human form, which is much more naive, verging on the naive. His subjects are often awkwardly positioned and the faces have a uniform, almost caricatured, look: big eyes set in a wide face, heads atop narrow necks. The early works were often portraits of people in a landscape, a format he continued throughout life, and one which allowed him to combine lucrative portrait-painting with his passion for outdoor scenes.

Ironically, portraits of his family, many of whom did look similar to each other, are more nuanced, even the early ones. The NPG exhibition, Gainsborough’s Family Album, features 50 works and takes us through Gainsborough’s entire life, to his death, aged 61, from cancer. The most painted were his wife Margaret Burr, an illegitimate daughter of the third Duke of Beaufort (who brought money to the marriage in the form of a £200 annuity from her father’s estate), and his daughters Margaret and Mary. The portraits, often executed at speed, were used to demonstrate Gainsborough’s virtuosity to paying customers but they have an animation and intimacy missing from many of his commercial commissions.

The Gainsboroughs’ marriage was long-lived but difficult. They married in 1746 when Margaret was only 18 (and pregnant) and Thomas a year older. Thomas had many affairs, which may account for the rather resigned expression on Margaret’s face in several of the ‘anniversary portraits’ (they were painted, it is said, on their wedding anniversary). Among my favourites were the paintings of Gainsborough’s daughters as children. Margaret and Mary Gainsborough, the Artist’s Daughters, Chasing a Butterfly (c 1756)

In 1759 the Gainsboroughs moved to Bath where Thomas built up a following and began to attract fashionable clients. He exhibited at the Society of Arts and the Royal Academy. Gradually he acquired a national reputation and was invited to become a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1769. His family portraits played a central role in his fortunes: they were painted as show pieces, to advertise his virtuosity. Although he preferred painting landscapes, these did not sell, but portraits (‘this curs’d face business’ in Gainsborough’s words) was another matter.

Among the most moving of them is ‘The Artist’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly’ (c 1765), the symbolism of which perfectly combines the fleeting nature of childhood and the enthusiasms of youth, and it captures the dynamics of the relationship between Margaret and Mary. The elder daughter gently restrains the younger, who has reached for the butterfly that has landed on a thistle. Life was indeed a delicate balance for the girls. As young women they fell for the same man. Mary married him but the marriage lasted only a few months after which she returned to the family, showed signs of mental illness, and was cared for by Margaret, who never married.

The Gainsboroughs’ move to 80 Pall Mall (Schomberg House) in 1774 represented a significant social step up. Photo © N Chadwick. Available for reuse under this Creative Commons licence

In 1774 the family moved to Schomberg House in Pall Mall, where Gainsborough set up his studio. He had arrived. The great and the good beat a path to his door, keen to have their portrait painted by this most fashionable of artists: William Pitt, Johann Christian Bach, Mary Darby, lords and ladies without number, even George III and his family (he was the Royal family’s favourite portrait painter). In 1788 Gainsborough died of cancer at the age of 61 and was buried at St Anne’s Church, Kew.

Decades earlier, his talent had been spotted by his uncle, who left him a special bequest. Gainsborough used it to travel to London and train with the best and then he worked assiduously to improve his natural abilities. There can be few ten pounds in history that were better spent. The portraits of his family, full of light, love, warmth and movement, show his true delight, in them and in the images of them he created.

Early Gainsborough: ‘From the Obscurity of a Country Town’

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk

Ends 17 February 2019