To anyone who loves the Georgian era and has not yet visited Strawberry Hill House, the summer villa of collector, designer, author, MP, letter-writer and wit Horace Walpole (1717–1797), get yourself over to Twickenham, in south-west London before 24 February 2019.

It is a wondrous place, built as a fake Gothic castle, and well worth a visit at any time of year. For this exhibition, however, the Strawberry Hill Trust has borrowed a selection of Walpole’s collection of paintings, statues, artefacts, curios and relics and placed them in their original positions in the house. Not only that, they have briefed an army of volunteers who can explain the provenance and significance of the objects PLUS they’ve developed an app that gives you a tour of the building.

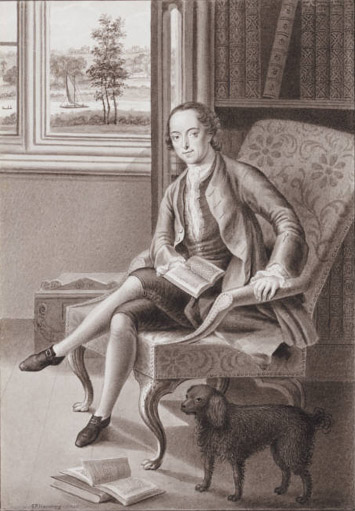

Horace Walpole (1795) by Henry Hoppner Meyer. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

As you navigate through the house, you get a strong sense of the personality of its erstwhile owner. Playful, waspish, intelligent, kind, generous, empathetic, witty, with a liking for what he called ‘gloomth’ (warmth+gloom).

A damp December Sunday afternoon was ‘perfick’ for the Gothic immersive experience. Horace would have stoked up the library fire, lit the lamps and cuddled his beloved dog Patapan. Such is the imprint of his personality on the house, as I navigated the extraordinary rooms I felt as if a ghostly Horace (officially Horatio, and ‘Horry’ to his friends) might just be waiting for me in the next room.

There were so many high points of the exhibition that I have chosen to talk about five of them.

1 ‘Eagle, on an altar base’ in the Great Parlour

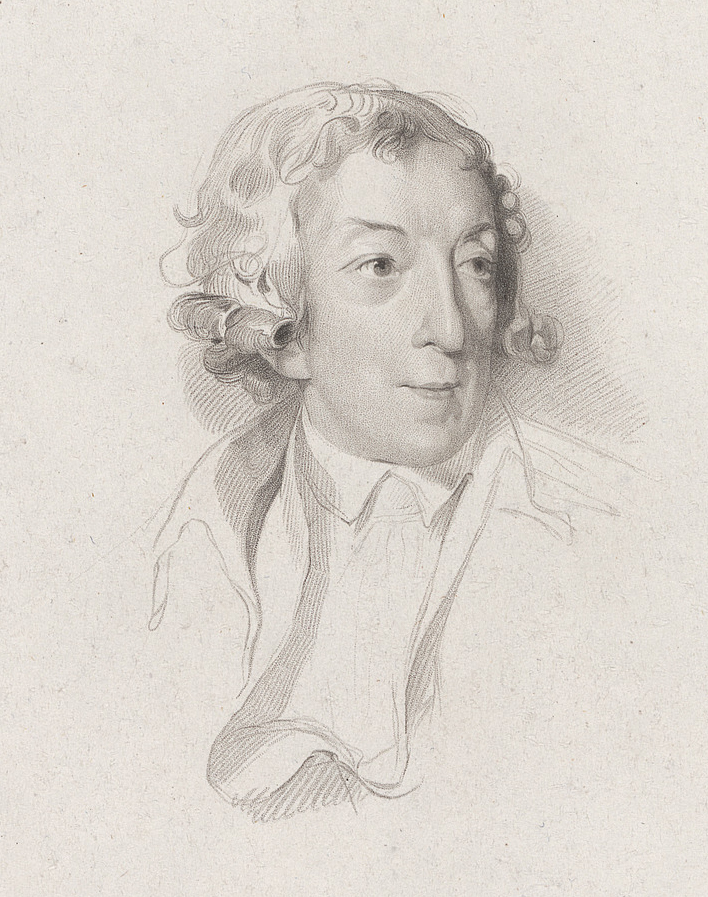

Walpole did the usual things boys of his rank did – Eton, Cambridge and in 1739 to 1741 the Grand Tour, accompanied by his friend Thomas Gray, the poet who went on to write ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’. Gray was quite an earnest fellow and conscious of the marked difference between him, the son of a clerk and a milliner, and Walpole, the son of the Prime Minister. They fell out during their travels and Gray stomped home on his own. Horace later blamed the rift on his own immaturity and they were reconciled some years later.

While they were in Rome Horace bought ‘Eagle, on an altar base’, a Greek 1st-century marble sculpture, 77.5cm tall. For the exhibition, it has been borrowed from the Earl of Wemyss & March and placed in the Great Parlour, where it stood until 1763, when it was moved upstairs to the Gallery.

Just as my companion was remarking that it was a miracle that the beak of the eagle was still attached after all these centuries, our room guide disabused us. The beak was broken off and stolen but was restored by Walpole’s cousin Anne Seymour Damer, an accomplished sculptor. They were close friends, so close that Horace left Strawberry Hill to her in his will. Damer was one of a number of female artists patronised by Walpole. Another reason to love him. He also opposed slavery.

Damer has been claimed by some as a lesbian and Horace’s own sexuality has also been a subject for speculation. There is not much firm evidence that he was gay but his on-off friendship with Henry Pelham-Clinton, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, lifelong lack of inclination to marry and a handful of luke-warm flirtations with women might point to it.

2 ‘Portrait of Sarah Malcolm in Prison’ in the Green Closet

In 1764 Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto, A Story. Translated by William Marshal, Gent. From the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St. Nicholas at Otranto, which is generally accepted as the first Gothic novel. Purporting to be translated from a manuscript recovered by an ‘ancient Catholic family in the north of England’, it told a lurid tale of supernatural happenings, ancient prophecies, illicit marriages, kindly priests, endangered heroines, long-lost sons and bloody murder.

Throughout Strawberry Hill House you can see indications of Walpole’s fascination with the heavy mysteries of Catholicism. He was not himself a religious man. Quite the contrary. From his days at Cambridge, he was sceptical of the tenets of Christianity and hated superstition and bigotry. However, it is easy to see why William Hogarth’s painting of the 22-year-old ‘Irish laundress’ and convicted murderer Sarah Malcolm would have appealed to him. She sits, apparently calm, her rosary in front of her, the Newgate prison door to her right. Its dark drama is entirely Gothic.

Twenty-three-year-old Malcolm, a laundress to residents of the Inns of Court in the Temple, acted as lookout while her friends carried out a robbery in the home of one of her customers. The gang took £300 worth of cash, silverware and other items and murdered the three inhabitants, two elderly women and their servant. Sarah denied murder but after a five-hour trial on 23 January 1733 the jury took 15 minutes to convict her. She was the only one of the gang to suffer punishment. The others were arrested but not charged. William Hogarth obtained permission to sketch her on the day before her execution in Fleet Street. His work was engraved and sold as prints many times over.

William Hogarth, Portrait of Sarah Malcolm in Prison (1733). National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

3 ‘Horace Walpole in his Library’ in the Library

As we went through the house, almost every room became my new favourite. Each had something so amazing, cute or unique that it superseded all we had seen before. The Library, with its Gothic-arched bookcases and view over the fields to the river (now obscured from view by buildings, but one can imagine) was my most favourite (can I say that?).

The books are not Walpole’s collection but on loan from a library without a home. The originals were dispersed after the sale of his entire collection in a 24-day sale by his heirs in 1842.

The stand-out artwork displayed here is a pen and ink and wash work by Johann Heinrich Muntz showing Horace Walpole in his library, standing to the right of the Library window, in the exact spot Walpole is shown in the drawing. This was a present to his cousin Henry Seymour Conway, who joked that Walpole looked too fat. He was famously spare of figure and ate little. The wan complexion he had as a sickly child never left him.

4 Cardinal Wolsey’s Hat in the Holbein Chamber

The Holbein Chamber, built as a bedchamber and with walls painted in royal purple (a greyish lilac), was designed to evoke the reign of Henry VIII and to house Walpole’s collection of 33 copies by George Vertue of famous Holbein portraits in the Royal Collection.

Unknown artist, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (1475-1530). Photo credit: Trinity College, University of Cambridge.

The Cardinal’s hat, for which there is no sure provenance, is wide and round-brimmed, not like that shown in portraits of Wolsey. To my untrained eye it does not look 500 years old but it does show Walpole’s whimsical side. He probably knew he’d been ‘sold a pup’ but didn’t care. He just wanted the hat for its Gothicky associations: a fall from grace, dangerous religion, tyranny. The Hair of Mary Tudor (Mary I) in a gold locket is displayed in a case in the Tribune. Same applies.

The confection of Strawberry Hill itself, built out with turrets and matriculations by Walpole, with its papier mâché fan ceilings and painted stone hallway, with paintings of his ancestors (and other people’s ancestors) is entirely a pretence. The hat could have been Wolsey’s. Why not just pretend it is!

5 Portrait of Frances Bridges, Countess of Exeter in the Gallery

Walpole hung this portrait by Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) of the widowed Countess of Exeter in the magnificent Gallery as if Frances Bridges were one of his own forebears. It was part of his playful take on the meaning of his pretend ancestral castle. Portraits of his father, mother (to whom he was devoted) and stepmother hang in the Great Parlour. The Walpoles were an old family but not grand and his father Robert was expected to become a sheep-farmer but became PM and the 1st Earl of Orford instead. Here, in the Gallery, are Medicis (more Gothic characters!), Sheffields, Marguerite de Valois. Altogether more exciting.

The Duchess of Exeter had her own Gothic past. The daughter of Lord Chandos, she was married first to Sir Thomas Smith of Abington, the Latin secretary to James I. After his death, she married Thomas Cecil, the first earl of Exeter, who died in 1622. Soon after she was accused of incest (with her step-son), witchcraft and attempting poisoning. James I got personally involved and issued fines to the accusers (her step-son’s wife and mother-in-law). She famously refused to be entombed next to her deceased husband in Westminster Abbey.

Suggested read: Art historian and provenance researcher Silvia Davoli’s account of her extraordinary discovery of an original Van Dyck (where you can also see the portrait).

The 1842 sale catalogue

Walpole’s own catalogue of his collection is online here: http://images.library.yale.edu/strawberryhill/index.html

Long Reads: Carrie Frye on The Gothic Life and Times of Horace Walpole

Strawberry Hill House & Garden

268 Waldegrave Road

Twickenham

TW1 4ST

Telephone: +44 (0)20 8744 1241