Having previously posted on Monstrosities of 1799 by James Gillray, I thought I would return to the subject of fashion, but this time looking specifically at how caricaturists portrayed women. It seems to me that the artists explored three main themes: the comical impracticality of particular styles, the over-revealing nature of women’s clothes and the absurd and dishonest lengths women went to to disguise their natural appearance.

Charles Ansell Williams, The Comfort and Convenience of Tight Dresses (1805). The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

In ‘The Comfort and Convenience of Tight Dresses’ (1805) by Charles Williams (1797–1830), who sometimes worked under the name ‘Ansell’ or ‘Argus’ and was employed between 1799 and 1815 by the prominent print publisher S. W. Fores, a woman puts her knee through her flimsy dress as she ties her shoelaces; a fat woman bursts the seam of her dress while she bends to pet a dog. The meaning is obvious: the fashion for narrow skirts is an affectation and the women wearing them almost insanely stupid. Indeed, ‘The next step it is thought will be into straigh [sic] waistcoats,’ appears in the bottom right-hand corner.

Caricaturists routinely presented images of fashion-following women for general derision and male titillation and sometimes both (note in Williams’ cartoon the woman on the left with her large and peachy backside, the fat woman’s bust generously overspilling her dress), so the late 18th-century thin gauzy white gowns, often worn with few undergarments, were a gift. Thomas Rowlandson was very fond of nipples showing through tight dresses.

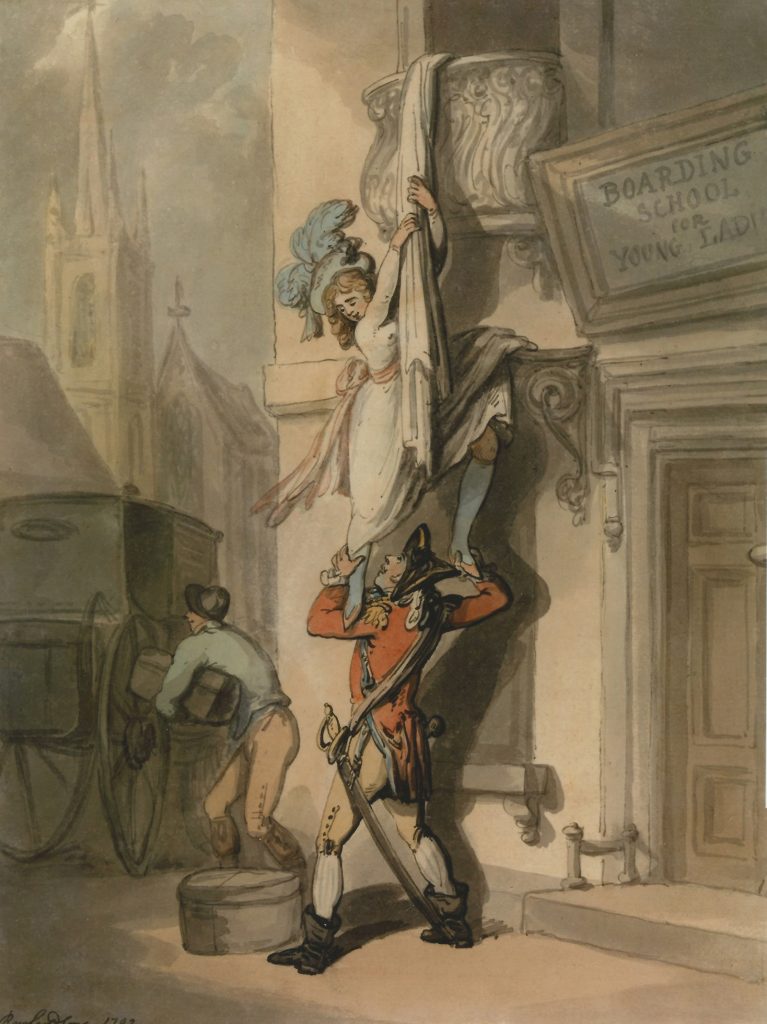

Thomas Rowlandson, The Elopement, 1792.

In ‘A Peep into Brest with a navel review!’ by Richard Newton (1777–1798), two women wear gowns split to the waist, their pert bosoms and rounded bellies on full display while a man holding an eyeglass views them with appreciatively. Although not overtly violent, the punning title uses military terms that carry with them an implicit reference to strategy, assault, conquest and victory. The women are prizes to be captured and plundered.

Richard Newton, A peep into Brest with a navel review! London : Pub. by R. Newton, No. 26, Walbrook, 1794 July 1. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The outfits in the cartoon is so extreme that we naturally wonder whether fashionable women really walked around with their breasts out. Apparently yes, they did, although it is unlikely that they did this anywhere other than private London soirées and parties given by the ton. Sir Gilbert Elliot’s account of Lady Anstruther’s ball in 1793 included a description of women wearing ‘an imitation of the drapery of statues and pictures, which fastens the dress immediately below the bosom, and leaves no waist… This dress is accompanied by a complete display of the bosom – which is uncovered, and supported and stuck out by the sash immediately below it.’1 Thomas Rowlandson showed women completely décolletées, but these were scenes either of intimacy as in ‘The Sailor’s Return’, in which the woman is possibly a prostitute, or drunken poverty, as in ‘Angry Scene in a Street’.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Sailor’s Return (undated); Angry Scene in a Street (between 1805 and 1810) Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Exposed bosoms apart, the late 18th century was generally a period when women could be more comfortable in their fashionable gowns. Thin white dresses had been worn in Europe since around 1780, a fashion driven in part by the new availability of chlorine bleach but also inspired by the aims of the French Republicanism – simple, pared down, ‘peasanty’ flowing designs reflected the values of the Revolution in a way that hot, costly, elaborate, multi-layered gowns did not.

Robert Dighton, A fashionable lady in dress & undress (1807). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Finally, we turn to the creation of an elegant fashionable woman from a shrunken husk. ‘A Fashionable Lady in Dress & Undress’ is a before-and-after showing a bald scrawny middle-aged woman at her toilette. Only with the help of cosmetics and creams, and a stylish wig and gown, not to mention a high-necked under-dress, is she changed into an acceptable version of herself: younger, smoother, prettier. The messages are clear: women’s value lies in their appearance, age certainly does not equal beauty, and women, being the deceivers they are, will do everything they can to trick the beholder into thinking them better-looking than they really are. As a side note, it is interesting to note that the caricaturist, Robert Dighton (1751–1814), had an additional career as a concert singer, so perhaps he was used to seeing female artists transform themselves before performing for an audience.

Nearly every example of caricature showing women and fashion displays a troubling misogynistic attitude. Whether women took exception to their portrayal as vain, shallow creatures too stupid to make rational choices even about the clothes they wore, or just sighed and got on with life while men chortled over their print collections, we don’t know.

Certainly caricaturists also targeted men for their fashion choices – there are plenty of effete ‘macaronis’ and dandies preening and prancing in fashionable garb – but arguably women’s bodies, their non-standard shapes and sizes, always seemingly encased in some ill-advised costume, were more often sneered at, and in more ways, than were men’s. There is little gentle ribbing. The comedy is usually sharp and vicious. And surely the pens of the caricaturists captured the male gaze in the way that later seaside postcard artists would: behind the façade of jeering, bold and unapologetic machismo was a malevolent mix of desire, contempt and sexual anxiety. At times, while perusing the archives, the centuries seem to melt away.