After 16-year-old Maria Glenn was taken from her home in 1816 and narrowly escaped forcible marriage to a local farmer, her uncle claimed that those involved had tried to destroy her reputation by impersonating her doing disreputable things. The case of Ann and Eleanor Weston has some similar themes – committing perjury on the marriage licence and ‘personation’, the crime of fraud through pretending to be someone you are not – although the circumstances are very different. My book about the Maria Glenn case is available from Pen & Sword (hardback and ebook).

After 16-year-old Maria Glenn was taken from her home in 1816 and narrowly escaped forcible marriage to a local farmer, her uncle claimed that those involved had tried to destroy her reputation by impersonating her doing disreputable things. The case of Ann and Eleanor Weston has some similar themes – committing perjury on the marriage licence and ‘personation’, the crime of fraud through pretending to be someone you are not – although the circumstances are very different. My book about the Maria Glenn case is available from Pen & Sword (hardback and ebook).

One Sunday in April 1810 John Thompson, a middle-aged jeweller, decided to visit St Paul’s Cathedral. He had not come to attend a service but to see Lord Nelson’s tomb in the crypt.

Nelson’s Sarcophagus in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, from Thomas Allen, The history and antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and parts adjacent (1827). London: Cowie & Strange.

During his visit he noticed an attractive young woman and, instantly infatuated, stalked her to her home half a mile away at 12 Fetter Lane, where he more or less barged through the door in order to make her acquaintance. From then on set he laid siege to Eleanor Weston, desperate to persuade her to have sex with him. A few weeks later she did and he promptly moved in with her and her sister Ann. He told them he was a widower.

It was not happy ever after. There were pressures on the relationship. Thompson was often away in Birmingham where he owned a factory producing paste (fake) diamonds and Eleanor’s friends were beginning to shun her: cohabiting was not respectable. She begged Thompson to marry her and he agreed.

Old Mitre Court, off Fleet Street. Eleanor Weston and her sister Ann lived here in 1810. © Copyright Martin Addison and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

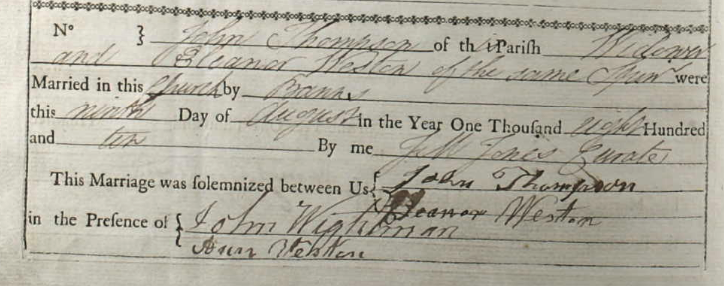

In July the banns were read at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street and on the morning of 9 August Thompson married Eleanor there. The sexton gave Eleanor away and Ann signed the register as a witness. Afterwards, there was a wedding dinner at Mitre Court, Fleet Street in the home of Susannah Currie, who ran a fruit and oyster shop and later that day, one of Thompson’s friends, Thomas Evans, dropped by on the couple at their home in St John Street to congratulate him.

The register shows that Eleanor Weston and John Thompson were married by the Curate on 9 August 1810 at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, witnessed by John Wightman, the parish clerk, and Ann Weston, Eleanor’s sister.

In October Thompson went with Eleanor to meet the in-laws who lived in Portsea, Hampshire. Eleanor’s other sister and mother were much relieved that Eleanor’s situation had been regularised, even if her new husband, at 46, was on the elderly side. Then Eleanor became pregnant and soon afterwards, in March 1811, Thompson abruptly left London and disappeared for 12 weeks. When he returned he had something to confess to his wife: Margaret Jeffs, his wife of 23 years, was not dead but still living in Birmingham, although very ill and not expected to be around for much longer. He would he happy to marry Eleanor (properly) again once Margaret had departed this world. Then he left again, probably going off to Birmingham to see Margaret, who duly died in June.

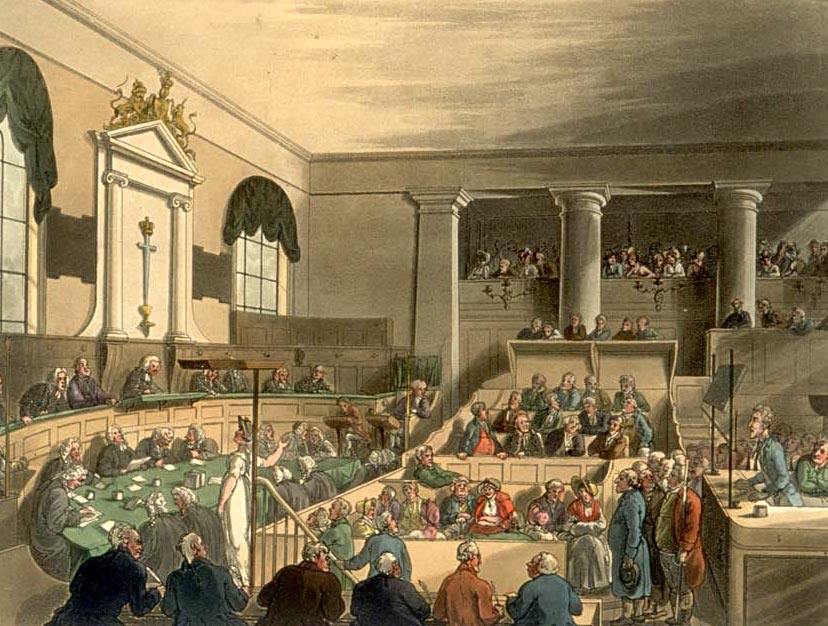

Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin, A trial at the Old Bailey in London from Ackermann’s Microcosm of London (1808–11).

The revelation left Eleanor in a terrible pass. Her child would be a bastard and her relationship with Thompson was bad and getting worse, so much so that he withdrew his offer to re-marry her. The best she could do after the baby was born was to ask him for maintenance of the child and money for the rent, and this she did.

Meanwhile, Thompson was mulling things over. Clearly Eleanor and Ann could ruin him. They could prove he had committed a bigamy and perjury, so he had them arrested and prosecuted for conspiracy, claiming that they had hatched a plot to make it look like he had married Eleanor at St Bride’s by paying an ‘unknown man’ £2 to ‘personate’ him and sign the register. He said that Eleanor had told him that she was angry at her loss of reputation and that she and Ann had dressed as washerwomen for the wedding so that no one would recognise them.

While Eleanor and Ann were in prison awaiting trial, Thompson sent his attorney, Mr Draper, to see their mother, Eleanor Weston senior. He made her an offer: Drop the demands for maintenance for the child and Thompson would drop the prosecution. Mrs Weston gave him short shrift.

Baron Gurney, after Unknown artist, print, 1832 or after. Credit: National Portrait Gallery.

The trial of the Weston sisters at the Old Bailey started on 19 February 1812, at about 5pm, with Thompson represented by John Gurney and Peter Alley defending the Westons. Thompson’s lies caught him out. He swore it was not his signature on the register but two solicitors proved that he had tried to disguise his signature as he wrote it, that he had deliberately made it look like a forgery so that he could later deny it. He claimed he had an alibi for the wedding. On the afternoon of 7 August 1810, he said, two days before the ceremony, he boarded a coach to Birmingham, arriving at 11am the next morning and stayed for the next 10 days tending to his wife and his business. But the only witness who swore to this was housekeeper.

By midnight it was all over. The jury acquitted the sisters without hesitation. Thompson slunk out of the court and before long the tables turned. In December the Weston sisters brought an action for malicious prosecution. Their case was heard at the Court of Common Pleas and after an hour’s deliberation the jury awarded them the sum of £2000 with damages of £5000.

They probably never saw the money, as in early 1813 Thompson was declared bankrupt.

I can find no trace of a prosecution of Thompson for perjury or bigamy.

References

The Extraordinary Trial, at Length, of the Two Misses Eleanor and Ann Weston