St Pancras Old Church

Although I visit the British Library from time to time I always find myself too exhausted or too worried about getting stuck with rush hour crowds to spend an hour or so at St Pancras Old Church. Luckily, I was meeting an American cousin at her hotel in King’s Cross and doubly luckily she was keen to come with me to take a look, so together we headed north through the regenerated splendour of Granary Square and up by the Regent’s Canal. It takes only about 15 minutes to walk there from Euston Road.

Charles Pye, 1777–1864, British after John Preston Neale, 1771/80–1847, British. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The church is one of the few dedicated to St Pancras, the patron saint of children.1 Its establishment dates back to the 4th century which makes it one of the oldest places of Christian worship in London.

Unfortunately, there is not much of the medieval church left, although the interior includes, on the north wall of the nave, a section of exposed Norman masonry. Most of the church is mid-Victorian. It was extensively rebuilt in 1847 by architects Roumieu and Gough who replaced the old tower and restored the exterior. By then the church had fallen into disuse and dereliction, having lost its status as a parish church when St Pancras New Church on Euston Road was built in 1819–22. Further changes were made in 1888, in 1925 and in 1948 following wartime bomb damage.

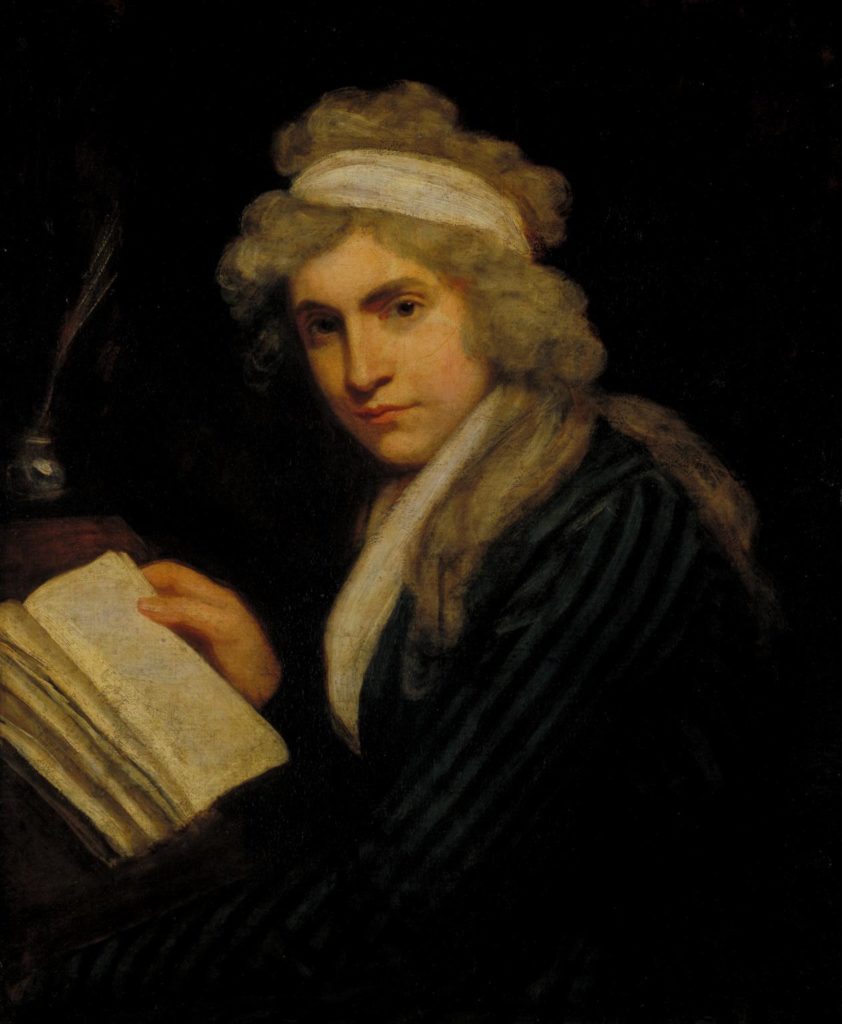

Mary Wollstonecraft c.1790-1 by John Opie 1761-180. Purchased 1884. Photo © Tate. Reproduced under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported).

In 1797 Mary Wollstonecraft, who died shortly after giving birth to her daughter Mary Godwin (later Shelley), was buried at St Pancras Old Church. Her grave was where 16-year-old Mary Godwin was said to have planned her elopement with Percy Bysshe Shelley (and maybe did did other less decorous things). After Mary Shelley died of a brain tumour in 1851, her son Sir Percy Florence Shelley had the bodies of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin disinterred and moved to Bournemouth because his mother had expressed a wish to be buried with her parents. Percy Shelley’s heart, which famously survived his funeral pyre2 and was for years preserved by Mary in a silken shroud, was also buried with her.

There is a memorial stone to Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin in the churchyard at St Pancras.

Near the Wollstonecraft-Godwin memorial is this memorial, built in 1816.

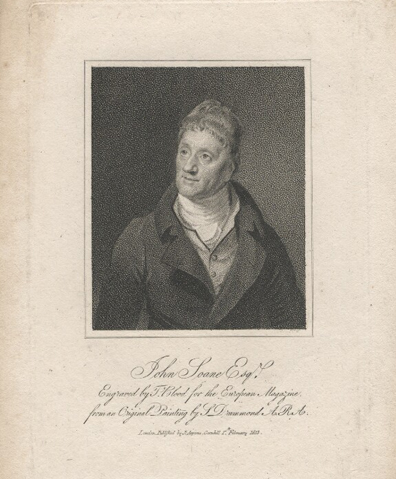

The mausoleum of Sir John Soane and his wife Eliza, built of Carrara marble and Portland stone.

I was quite surprised to find that it was designed by Sir John Soane (1753–1837) for his wife Elizabeth Smith (“Eliza”), who died in 1815. To me, it is an unattractive assemblage of shapes and quite unlike the home of the architect and antiquary in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which is the epitome of neoclassical elegance. One interesting thing, though, is that the central structure inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design for telephone boxes.

Elizabeth Soane, née Smith, by John Jackson (1778-1831). Public Domain

The inscription on the memorial reads:

Sacred To The Memory of Elizabeth, The Wife of John Soane, Architect She Died the 22nd November, 1815.

With Distinguished Talents She United an Amiable and Affectionate Heart.

Her Piety was Unaffected, Her Integrity Undeviating, Her Manners Displayed Alike Decision and Energy, Kindness and Suavity.

These, the Peculiar Characteristics of Her Mind, Remained Untainted by an Extensive Intercourse With The World.

Neither of the Soanes’ two sons wanted to follow their father into architecture, which was a huge disappointment to Sir John. John, the elder of them, was lazy and uninspired, but the younger, George, was positively fizzing with animosity towards his parents. He married to spite them and when Eliza, then frail with gallstones, discovered that he was the author of an anonymous attack on the architectural work of his father, she fell ill and died soon afterwards. When Sir John found out that that George was living in a ménage à trois with his wife Agnes and her sister, and that he was abusing them and their children, he all but cut him out of his will. Both Soane, who died in 1837 and his son John, who died prematurely in 1823, joined Eliza in the mausoleum.

Many of the graves were removed in the 1860s (see below) but some have been retained, and a number of those are Catholic. On the north side of the church you will see the tomb of Edward Carpue (1740–1792) and his and wife Mary Carpue née Hodgson (1758–1806) and five of their children. The Carpue family was originally from Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, and was also associated with the Lincoln’s Inn Fields area.

In 1760 Edward’s mother Anne Smallwood worked with Richard Challoner (d. 1781), a leading figure of English Catholicism, to set up a girls’ Catholic boarding school in Hammersmith. Edward and his brother Charles were Secretary and Treasurer of the Associated Catholic Charities, also set up by Dr Challoner.3 Joseph Constantine Carpue, a surgeon and anatomist who was said to have performed the first aesthetic “nose job” in 1814, was a second half-cousin.4 Despite his Catholicism, Edward Carpue, a vestryman at St Clement Danes and a juryman at the Old Bailey, who had a shoemaker business in Serle Lane, Holborn, was clearly respected and trusted. Sadly, his life was relatively short. In 1792, at the age of 52, he died of a stroke.

Other residents of the churchyard include the criminal thief-taker Jonathan Wild (d. 1725), composer Johann Christian Bach (d. 1782), John William Polidori (d. 1821), the young doctor and writer of The Vampyre, who accompanied Lord Byron on his European journey in 1816, the Chevalier d’Eon (d. 1810), a French transgender diplomat and spy. There is also the ‘Hardy tree’, an ash encircled with numerous overlapping gravestones, supposedly placed there in the mid 1860s by novelist Thomas Hardy when he was a lowly draughtsman given the task of exhuming and reburying human remains to make way for the railway lines.

The churchyard certainly has plenty to interest fans of the Long 18th Century like myself. The Church is Grade II listed and has a thriving performance programme.

- Pancras, a 14-year-old Roman, converted to Christianity and would not renounce his faith. He was beheaded by Diocletian in 304 AD.

- Possibly because it had calcified as a result of tuberculosis.

- History of the Sardinian Chapel.

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, 62, 2, p674.