Execution is, of course, irrevocable. Mistakes cannot be corrected. In the conviction in 1819 of two men for the murder of Isabella Young four years previously we see an example of how easy it was to arrive at the wrong verdict and what could be done about this afterwards.

The person who killed 20-year-old Isabella Young on the night of 28 August 1815 must have been armed with something heavy such as a hammer or poker. She was found with several deep head wounds, her skull was fractured and her jaw broken in several places.

Isabella had only been employed at Herrington Hall, which was situated close to the Sunderland road in East Herrington, County Durham, for four days before her 65-year-old mistress Miss Jane Smith left home to collect farm rents from her estates. Miss Smith planned to be away for 10 days, during which time Isabella was sent to lodge elsewhere in order to save her employer money on heating and lighting, but she was instructed to go back to sleep at Herrington Hall the night before her mistress was due to return.1

Every day while her mistress was away, Isabella came back the house to clean, sometimes alongside Hannah Crinson, an 80-year-old widow and domestic servant who had previously worked for Miss Smith but who was now retired. On Tuesday 22 August, they were in the kitchen cleaning the pewter when a tall, shabbily dressed man with a long pale face came to the door claiming that he wanted to talk to Miss Smith about renting one of her collieries. He made himself at home at the kitchen table and expounded on his plans, much to their surprise and annoyance, and after an hour went on his way. Although he seemed sober enough, they thought he was shifty.

On the evening before Miss Smith was expected home, Monday 28 August, Isabella told Elizabeth Clark, the wife of a waggoner in the village, that she had heard noises at the door, as if someone was trying to get in, and she asked Elizabeth’s daughter Ann Howe, who lived 50 yards from Herrington Hall, to come back to stay with her overnight. Ann agreed only to walk back to the house with Isabella, but waited outside while Isabella locked the door from the inside and called out from the upstairs window that she was safe in her room. This was at about 10pm.

At two in the morning, John Stonehouse, the village blacksmith woke up and lay in bed for ten or 15 minutes gazing the strange lights dancing on the ceiling. Belatedly he realised that there was a fire somewhere. When he looked out of the window he saw Herrington Hall blazing. Throwing on his clothes, he ran downstairs, raised the alarm in the village and raced towards Miss Smith’s house along with his brother James and a fellow blacksmith, Joseph Turnbull.

At the house they called out to Isabella, but there was no answer. When they tried the front door, which was closed but not locked, they saw her lying face down in the passage to the kitchen wearing only her shift and clutching her flannel petticoat in her left hand. John Ramsay, the village cartwright, managed to grab her arms, pull her out across the road and sit her up, but it was to no avail. She was dead. Someone was sent to inform Miss Smith.

After dawn broke, surgeon John Croudace was fetched from Bishopwearmouth to examine the body. Isabella had clearly been the victim of an astonishingly brutal attack. Her head was a bloody mess. There were several deep head wounds, her skull was fractured and her jaw broken in several places.2

She had no burns and she was not with child. When Croudace had finished, Isabella’s body was lifted into an old wooden box, carried out to an outhouse in the back yard and covered with a horse cloth. 3 The Durham coroner, Samuel Castle, was sent for. People in the village talked about seeing three strangers hanging about the village in the days before the fire, and concluded that they must have been responsible.

The shock for Miss Smith on her return must have been intense. As there was no source of water nearby, the fire had burned on until only the walls of the house remained. Everything, including all her valuables, legal documents, deeds, securities, and cash, which she stored in her bedroom above the kitchen, had been stolen by the intruder who had killed Isabella or had been destroyed in the fire. An inquest held in the village.

It was abundantly clear that the property, and not the fate of poor Isabella, was what was most important to Miss Smith. She began sifting the hot cinders looking for old nails, hoops, hinges, bolts and locks, anything salvageable, and a rumour went around that rather than pay for lodgings Miss Smith was sleeping in the same box that had been used to store Isabella’s corpse, which was now buried at St Michael’s Church in Houghton-le-Spring.

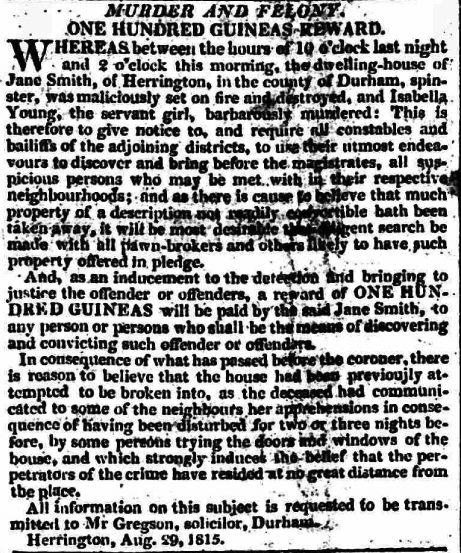

After a few days, probably at the insistence of her solicitor Mr Gregson, Miss Smith offered a reward 100 guineas (£104). The authorities also promised to extend a ‘Prince Regent’s pardon’ to anyone who was tangentially involved (as long as they were definitely not involved in the murder or the arson), if they identified the perpetrators, and an additional cash reward was advertised by the Bow Street Runners, bring the total to £200. The Home Office ordered a Bow Street officer to go up to County Durham to investigate.4

Handbills were distributed and posters pasted up. The murder had shocked and terrified the county, if not the entire country. ‘A Citizen’ wrote to the editor of the Durham County Advertiser pleading for a coherent police force who could rid the area of ‘rogues, vagrants, and other disorderly persons.’5

Who was Miss Smith? An only child related to the Smythes of Esh, and distantly to George IV’s mistress Maria Fitzherbert, Miss Smith was from an old Catholic family and had inherited Herrington Hall and large and valuable estates, including farms and collieries, from her father Mathew. Newspaper accounts of the murder made no bones about her character, stating baldly that she was well known to be extremely wealthy but also miserly. In fact, she was parsimonious to the point of criminality. In 1786, aged about 35, she and her father became involved in an argument with the keeper of the turnpike gate at West Rainton. They claimed they did not need to pay the toll, having already passed through it that same morning, and rode off. The gatekeeper sued them because he knew they were lying, and won. The Smiths were fined £10 each. There were other incidents of a similar nature.

After the fire, Miss Smith decamped to lodgings at Bishopwearmouth where her behaviour attracted attention and concern. At a furniture auction she was found to have stolen a woman’s valuable shawl; a grocer kept her talking by a fire after seeing her put a pound of butter in her pocket, so that it melted and ran down her petticoats. Soon William Reid Clanny,6 an Irish doctor living nearby, saw potential in her vulnerability and introduced her to his friend Sir Robert Peat, one of many chaplains to the Prince Regent (he never actually met his royal patron) and quite a character in his own right. The son of a respectable watchmaker and silversmith of Hamsterley, County Durham (24 miles from East Herrington), Peat was 20 years Miss Smith’s junior, small, dapper, intelligent (he was a Doctor of Divinity from Cambridge), and a prolific gambler with expensive tastes, such that he was now very much in need of a wealthy wife.

Miss Smith accepted Sir Robert’s proposal, married her beau on 6 November 1815 and became Lady Peat. Although the settlement ensured that his wife retained half of her income for her exclusive use, Sir Robert now had £1000 a year to play with. After an attempt to introduce his wife to society in London proved an embarassing failure, Lady Peat moved back to Sunderland, to Villiers Street, where her weird habits continued. She would call on neighbours at mealtimes, in order to be fed for free, and filched cheap household objects from them. Whenever she was threatened with prosecution she would be forced to make financial restitution, often for sums hundreds of times more than the value of the stolen items. She and Sir Robert lived more or less separate lives, seeing each other only once or twice a year.

Meanwhile, what was happening in the investigation into Isabella Young’s murder? Sadly, it was a good example of how difficult it was to detect crime without photography or real scientific proofs. In early October 1815 The Globe reported that two unnamed brothers, ‘sons of a respectable tenant of Miss Smith,’ had been arrested on the coast of France and were being taken to Durham.7

Nothing further appears to have come of this, and it was not until nearly three years after the crime, in early 1818, that an impoverished itinerant was arrested and brought before magistrates. But there was no real evidence against him and he was discharged. Later, he was discovered in Morpeth, Northumberland – probably trying to claim poor relief – and, as the Poor Law required, was returned to Sunderland, where he accused a man called James Wolfe, with whom he had once worked in a quarry, of the murder.

Wolfe, a former tenant farmer who in 1814 had been evicted by Lady Peat for not paying his rent, was arrested in October 1818 in Carlisle and taken to Sunderland on suspicion of being an accessory.8

His son George, a furrier (he cut rabbit fur), was arrested in Edinburgh and taken to Durham gaol. A pocket-book found on him was thought to belong to Lady Peat, but because she refused to come and identify it, the magistrate released him on bail.9

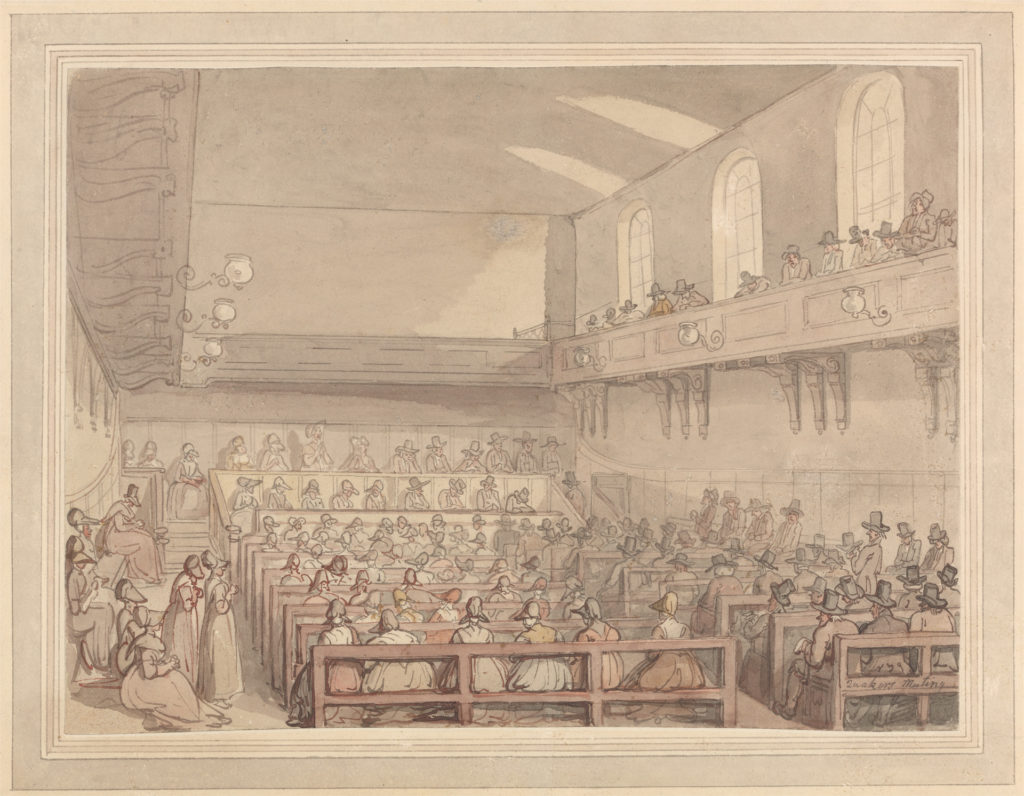

Another suspect was arrested, this time on the word of James Lincoln, an old mariner from Sunderland. On 13 August 1819 John Eden, a soldier in the Durham militia, James Wolfe and his son George appeared at Durham Summer Assizes at Durham Shire Hall in Old Elvet charged with burglary, murder and arson. Hundreds of people turned up to catch a sight of the accused men and the courtroom was packed. Among those watching were George’s employers, two Sunderland Quakers, John Mounsey and Thomas Richardson.10

The trial, heard by Mr Baron Wood, lasted all day, starting at 8am and finishing 15 hours later. The evidence was entirely circumstantial. The principal witness against Eden was his friend of 20 years James Lincoln, who swore that on 28 August 1815 Eden had come to his lodgings in Sunderland and urged him to accompany him and James Wolfe to rob Herrington Hall, during which he would probably ‘have to make away with that poor lass’, meaning Isabella Young. Ann Howe, who had accompanied Isabella to her door on the fatal night, swore that she and Isabella had walked along the road on the Sunday before in the company of Eden, who had seemed very familiar with Isabella, saying he would be up to see her ‘some night this week’, although Isabella did not seem keen. Lady Peat said that a pocket-book found on George Wolfe was the one she left on her desk (he said it had belonged to his father-in-law). James Shaw claimed that in 1814 James Wolfe threatened to rob Miss Smith after he was thrown off his farm.

At the end of the proceedings, the jury retired to a private room and an hour and three-quarters later emerged with their verdict. John Eden and James Wolfe were guilty. George Wolfe was not. Eden’s wife uttered a dreadful shriek and was taken out of the courtroom in a ‘state of insensibility’. Baron Wood, as he was obliged to do by law, proceeded to pass sentence of death on the prisoners.

Baron Wood was not convinced that the correct verdict had been given and was not alone in his doubts. Mounsey and Richardson, sure that the men were innocent, went to see the judge, who respited (deferred) execution, which in normal circumstances would have been carried out on 16 August, three days after sentencing. There was a good deal of suspicion about the motives of James Lincoln and James Shaw. Why had they waited three years to tell their stories? Were they corrupted by the prospect of reward money?

With the help of Mr Greenwood, a Durham solicitor, Mounsey and Richardson produced affidavits which gave cogent alibis for both men. Their evidence was solid, based on documentation: log books, paybooks, receipts. At the time of the murder Wolfe was working at a quarry near Cockermouth, nearly 100 miles from East Herrington. After drinking for two days in Newcastle, Eden had been incarcerated in the guardhouse in Newcastle, but crucially Lincoln’s claim that Eden had come to his lodgings in Sunderland on the evening of 28th suggesting he accompany him to East Herrington to commit the crime was disproved because Lincoln was not even in Sunderland. He had been working on a sloop called the William & Mary and was at Marsk-by-the-Sea on the Yorkshire coast, nearly 40 miles away.

Royal pardons were granted to Eden and Wolfe and Lincoln was indicted for perjury. He was found guilty at a trial in August the following year, but the case was referred to the 12 Judges who decided for procedural reasons that the conviction was wrong.11

And what of Sir Robert and Lady Peat? He died at Brentford in 1837, and she departed five years later, aged 91 or 92, leaving property worth around a quarter of a million pounds. Poor Isabella Young, who was reduced in so many newspaper reports merely to ‘Miss Smith’s maid’, was forgotten.

- Most of the account of Isabella’s murder comes from ‘Lady Peat and the Herrington Tragedy’ in The Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend (1887). Newcastle-on-Tyne: Walter Scott; The Times, 4 Sept 1815, 3E; Anon, Trial for Burglary, Murder, and Arson at Herrington, at the Durham Summer Assizes, 1819. Durham: F. Humble and Co.

- The Hull Packet reported on 5 September 1815 that Isabella’s body was ‘dreadfully mangled’ and ‘both eyes were out, a deep wound in her neck’ but this does not match exactly the evidence the surgeon John Croudace was reported to have given at the inquest and the 1819 trial.

- In reports of Isabella’s death, there was no mention of her family or even of where she originally came from. At the inquest Miss Smith said that her servant had had a good reference from her previous employer Cuthbert Ellison (1783–1860), a Whig MP, who lived at Iveston, County Durham, and that she knew of no sweethearts, nor did she suspect she was pregnant.

- Tyne Mercury, 12 Sep 1815, 1C; Durham County Advertiser, 9 Sep 1815, 2D; Morning Chronicle, 4 Sep 1815, 3E.

- Durham County Advertiser, 9 Sep 1815, 3A.

- Clanny was known for inventing the Clanny mine safety lamp (a forerunner of the Davy lamp).

- Globe, 2 Oct 1815, 3B.

- Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser, 20 Oct 1818, 2E.

- Caledonian Mercury, 3 December 1818, 3B.

- Eden’s age was given as 28, James Wolfe, 56 and George Wolfe, 30.

- Russell, William Oldnall, Ryan, Edward (1839). Crown Cases Reserved for Consideration: And Decided by the Twelve Judges of England, from the Year 1799 to the Year 1824. Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, p. 421-24.